The art of hand-coloring or tinting black and white photographs has been around, the Vox video above explains, since the earliest days of photography itself. “But these didn’t end up looking super realistic,” at least not next to their modern counterparts, created with computers. Digital colorization “has made it possible for artists to reconstruct images with far more accuracy.”

Accuracy, you say? How is it possible to reconstruct color arrangements from the past when they have only been preserved in black and white? Well, this requires research. “You now have a wealth of information,” says Jordan Lloyd, a master digital colorist. “It’s just knowing where to look.”

Historical advertisements, diaries, documents, and the assessments of historians and ethnographers, among other resources, provide enough data for a realistic approximation. Some conjecture is involved, but when you see the amount of research that goes into determining the colors of the past, you will most surely be impressed.

This isn’t playing with filters and settings in Photoshop until the images look good—it’s using software to recreate what scholarship uncovers, the kind of digging that turns up important historical facts such as the original red-on-black logo of 7Up, or the fact that the Eiffel tower was painted a color called “Venetian red” during its construction.

Unless we know this color history, we might be inclined to think colorized photographs that get it right are wrong. However, the aim of modern colorizers is not only to make the past seem more immediate to us in the present; they also attempt to restore the colors people saw when photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries were taken.

The software may not dictate color, but it still plays an indispensable role in how alive digitally colorized photographs appear. Colorizers first use it to remove blemishes, scratches, and the signs of age. Then they blend hundreds of layers of colors. It’s a little like making a digital oil painting. Human skin can have up to 20 layers of colors, ranging from pinks, to yellows, to blues.

Without “an intuitive understanding of how light works in the atmosphere,” however, these artists would fail to persuade us. Color is produced by light, as we know, and light is conditioned by levels of artificial and natural light blending in a space, by atmospheric conditions and time of day. Different surfaces reflect light differently. Correctly interpreting these conditions in a monochromatic photograph is the key to “achieving photorealism.”

Critics of colorization treat it like a form of vandalism, but as Lloyd points out, the process is not meant to substitute for the original artifacts, but to supplement them. The colorized photos we see in the video and at the links below are of images in the public domain, available to use and reuse for any purpose. Colorization artists have found their purpose in making the past seem far less like a distant country.

Related Content:

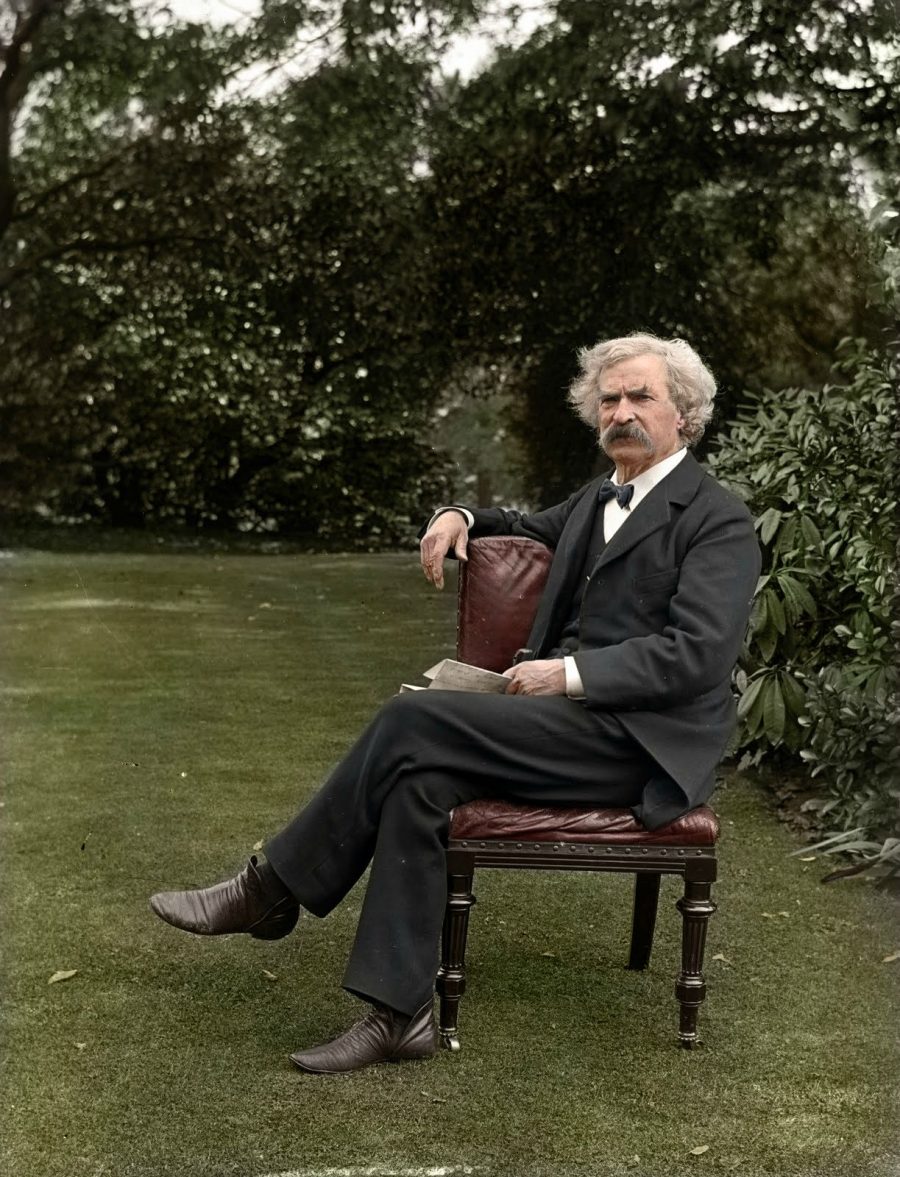

Colorized Photos Bring Walt Whitman, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller & Mark Twain Back to Life

The Opening of King Tut’s Tomb, Shown in Stunning Colorized Photos (1923–5)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply