Many people are cheated out of an authentic education in English literature because of a longstanding puritanical approach to its curation. One might spend a lifetime reading the traditional canon without ever, for example, learning much about the long history of popular pornographic British writing, a genre that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries as the popularity of the novel exploded. Everyone knows the Marquis de Sade, even if they haven’t read him, not least because he lent his name to psychoanalytic theory. Many of us have read Voltaire’s randy satire, Candide. But few know the name John Cleland, author of Fanny Hill, a bawdy British novel published in 1748, over forty years before de Sade’s Justine.

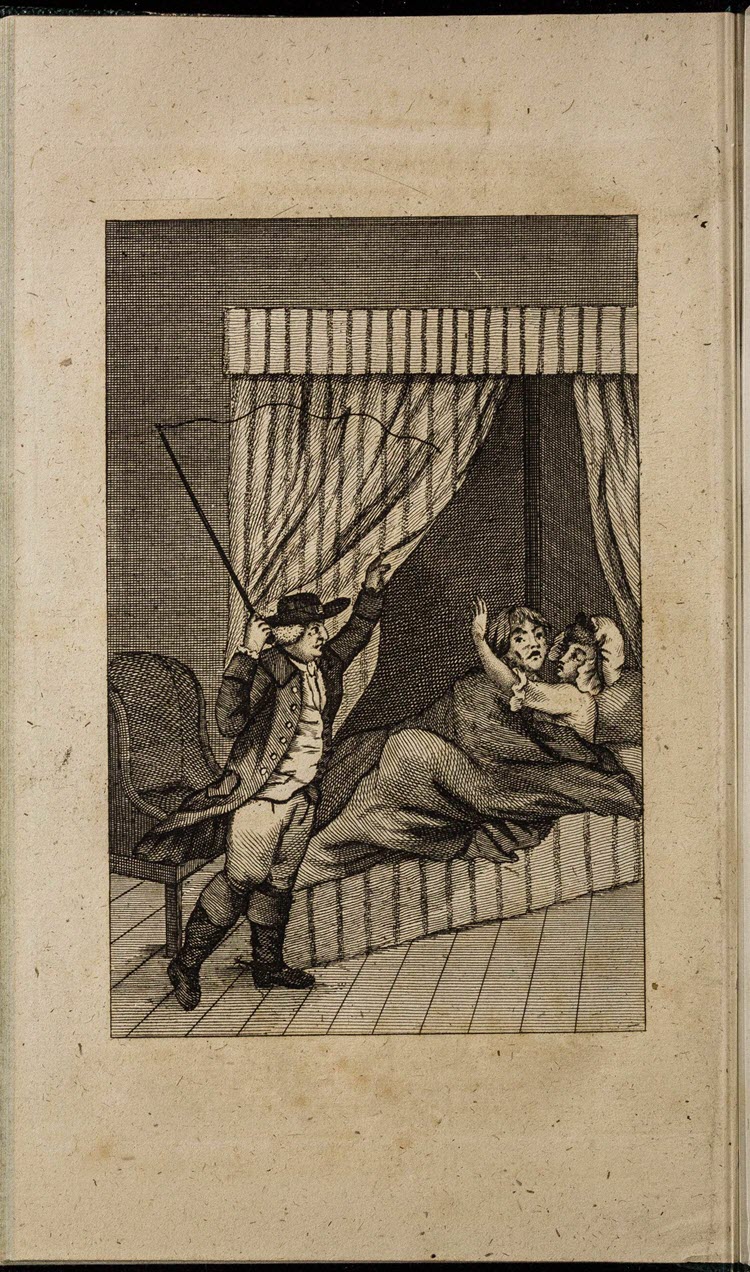

A book that serves up its own wealth of psychosexual insights, Fanny Hill does not disappoint either as pornographic writing or as entertaining fiction. Cleland wrote the book while in debtors’ prison, after he “boasted to James Boswell, himself no mean pornographer… that he could write a sexually exciting story of ‘a woman of pleasure’ without using a single ‘foul’ word,” writes John Sutherland at The Guardian. Cleland succeeded, in a narrative loaded with crudely Shakespearean puns and euphemisms. The wordplay in the title character’s name, an Anglicization of mons veneris (mound of Venus), will be immediately apparent to speakers of British English.

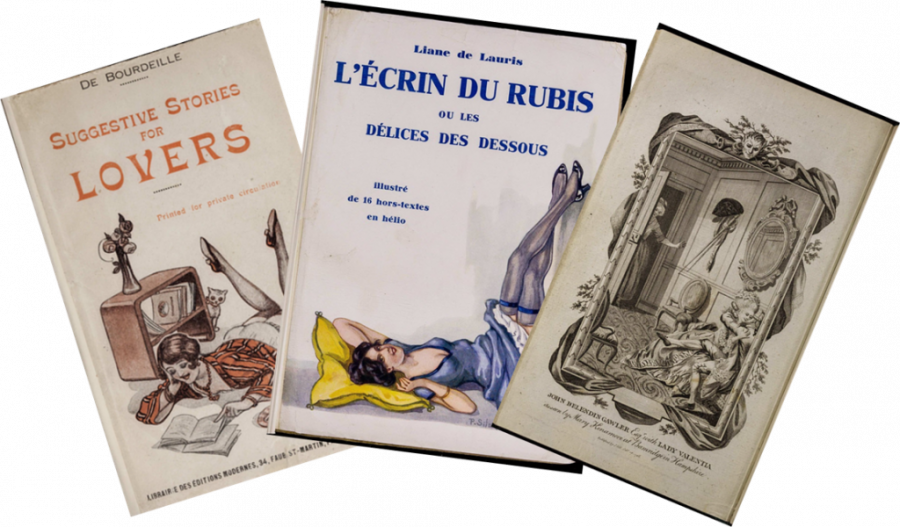

Upon its publication, however, Cleland was prosecuted for “corrupting the king’s subjects,” and the book was “duly buried and went on to become a centuries-long underground bestseller.” Such was the fate of many an obscene British novel. Thousands of these became property of the British Library, which “kept its dirtiest books locked away from the rest of its collections,” notes Brigit Katz at Smithsonian. “All volumes deemed to be in need of extra safeguarding so that members of the public couldn’t get their hands on the saucy stories—or try to destroy them—were placed in the library’s ‘Private Case.’” Now, they are being digitized and made available to Gale subscribers.

2,500 volumes from the Private Case collection have become part of Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender research library, the first time much of this material has been available. “Pretty much anything to do with sex,” says British Library curator Maddy Smith, was locked away “until around 1960, when attitudes to sexuality were changing.” Librarians only began cataloguing this material in the 1970s, but most of it remained obscure and fairly inaccessible. The collection dates to 1658. It includes a series called the Merryland Books, written in the 1740s by authors who took pseudonyms like “Roger Pheuquewell” and described “the female anatomy metaphorically as land ripe for exploration.”

It is not overall a body of work given to subtleties. Aside from some exceptions, like Teleny or The Reverse of the Medal, a tragic gay romance attributed to Oscar Wilde, these are also largely books “written by men, for men,” about women, Smith points out. “It’s to be expected, but looking back, that’s what is shocking, how male-dominated it is, the lack of female agency.” She might have also pointed out that many women in the mid-18th century were writing and publishing popular novels, largely read by women, with frank coming-of-age descriptions of sexual education, seduction, and even rape. And both men and women wrote about homosexuality and gender fluidity in ways that might surprise us.

The response to such books tended to be moralistic correction—as in the best-selling Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded by Samuel Richardson—or lascivious satire, as in the Merryland Books, Fanny Hill, and Henry Fielding’s Shamela, a parody that turns Richardson’s chaste heroine into a scheming prostitute. These two novels were massively popular and show the form as we know it developing as a literary conversation between men about women’s supposed vices or virtues. We should read mid-18th century pornographic literature as an essential part of the formation of the British novel tradition.

At the Gale online collection of these British Library treasures, one can do just that, then reach back a century earlier and forward 200 years to 1940, the last date in the Gale collection, which “makes available approximately one million pages of content that’s been locked away for many years, available only via restricted access.” (We must note that access is still restricted to Gale subscribers). These pages come not only from the British Library but also from The Kinsey Institute and the New York Academy of Medicine, who have both supplied a share of textbooks and scholarly monographs on sex. The “obscenity” of this material lies in the eyes of its keepers—much will seem unremarkable today, and some can still seem plenty scandalous.

Related Content:

Read 14 Great Banned & Censored Novels Free Online: For Banned Books Week 2014

John Waters Reads Steamy Scene from Lady Chatterley’s Lover for Banned Books Week (NSFW)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I am transcribing a commonplace book and diary of a well known Victorian politician which is crammed with obscene jokes and anecdotes dating from c1820 — 30. It surprised me that such a well educated and clever man should take pleasure in recording such material, which is often puerile in flavour. Has there been any study of erotic writing for private consumption ?