On May 26, 1969, John Lennon and Yoko One began their second “Bed-In,” a form of anti-Vietnam War protest that combined the media impact of a press conference with the comfort of hotel sheets. Their first Bed-In, which happened in various rooms of the Amsterdam Hilton in late March of that year, saw them grant interview after interview about peace all day long without moving from the bed in which they had ensconced themselves. They’d scheduled its follow up in New York City, but Lennon found he couldn’t enter the United States due to a previous conviction for marijuana possession. They relocated it to the Bahamas, where the heat soon prompted them to move again to the entirely cooler Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal. There they recorded the song “Give Peace a Chance,” aided by such visitors as Tommy Smothers, Dick Gregory, Murray the K, and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary.

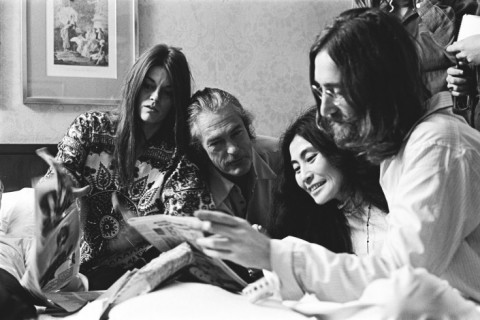

But Leary didn’t just come to provide a backing vocal. With his wife Rosemary, he recorded a conversation with Lennon and Ono about… well, about a variety of subjects, but they’d all fall under the broad heading of Leary’s one great pursuit, “consciousness.” Only recently did Leary archivist Michael Horowitz discover the transcript of this session in “an unmarked envelope in a box of miscellaneous papers,” and this week the Timothy Leary Archives made it available to the public for the first time ever. The conversation begins with the finer points of teepee life, moves on to the effects of place on one’s state of mind, touches on both couples’ having found themselves on the wrong side of drug law enforcement, and ends with Lennon and Leary comparing notes on how they use the media to convey their message:

TIMOTHY: John, about the use of the mass media … the kids must be taught how to use the media. People used to say to me–I would give a rap and someone would get up and say, “Well, what’s this about a religion? Did the Buddha use drugs? Did the Buddha go on television? I’d say, “Ahh—he would’ve. He would’ve….”

JOHN: I was on a TV show with David Frost and Yehudi Menuhin, some cultural violinist y’know, they were really attacking me. They had a whole audience and everything. It was after we got back from Amsterdam…and Yehudi Menuhin came out, he’s always doing these Hindu numbers. All that pious bit, and his school for violinists, and all that. And Yehudi Menuhi said, “Well, don’t you think it’s necessary to kill some people some times?” That’s what he said on TV, that’s the first thing he’s ever said. And I said, “Did Christ say that? Are you a Christian?” “Yeah,” I said, and did “Christ say anything about killing people?” And he said, “Did Christ say anything about television? Or guitars?”

To learn more about Lennon and Ono’s Bed-Ins, you can visit the 70-minute documentary Bed Peace (below), previously featured on Open Culture and still freely viewable on YouTube:

Related content:

Timothy Leary’s Wild Ride and the Folsom Prison Interview

Beyond Timothy Leary: 2002 Film Revisits History of LSD

Bed Peace Starring John Lennon & Yoko Ono (Free for Limited Time)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.