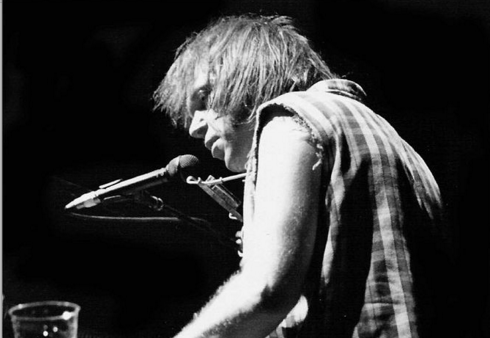

Image by F. Antolín Hernández, via Wikimedia Commons

Graham Nash, of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, has a new book out, Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life. And that means he’s doing interviews, many interviews. A couple of weeks ago, he spent an excellent hour on The Howard Stern Show (seriously). Next, it was off to chat with the more cerebral Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air.

In the midst of the interview (listen online here), Gross asked Nash to talk about his friendship with Neil Young, a man Nash has called “the strangest of my friends.” Just what makes him strange? Nash explains:

The man is totally committed to the muse of music. And he’ll do anything for good music. And sometimes it’s very strange. I was at Neil’s ranch one day just south of San Francisco, and he has a beautiful lake with red-wing blackbirds. And he asked me if I wanted to hear his new album, “Harvest.” And I said sure, let’s go into the studio and listen.

Oh, no. That’s not what Neil had in mind. He said get into the rowboat.

I said get into the rowboat? He said, yeah, we’re going to go out into the middle of the lake. Now, I think he’s got a little cassette player with him or a little, you know, early digital format player. So I’m thinking I’m going to wear headphones and listen in the relative peace in the middle of Neil’s lake.

Oh, no. He has his entire house as the left speaker and his entire barn as the right speaker. And I heard “Harvest” coming out of these two incredibly large loud speakers louder than hell. It was unbelievable. Elliot Mazer, who produced Neil, produced “Harvest,” came down to the shore of the lake and he shouted out to Neil: How was that, Neil?

And I swear to god, Neil Young shouted back: More barn!

To that we say, more Neil Young! Find more Neil right below.

Neil Young Busking in Glasgow, 1976: The Story Behind the Footage

‘The Needle and the Damage Done’: Neil Young Plays Two Songs on The Johnny Cash Show, 1971

The Time Neil Young Met Charles Manson, Liked His Music, and Tried to Score Him a Record Deal

Neil Young on the Travesty of MP3s