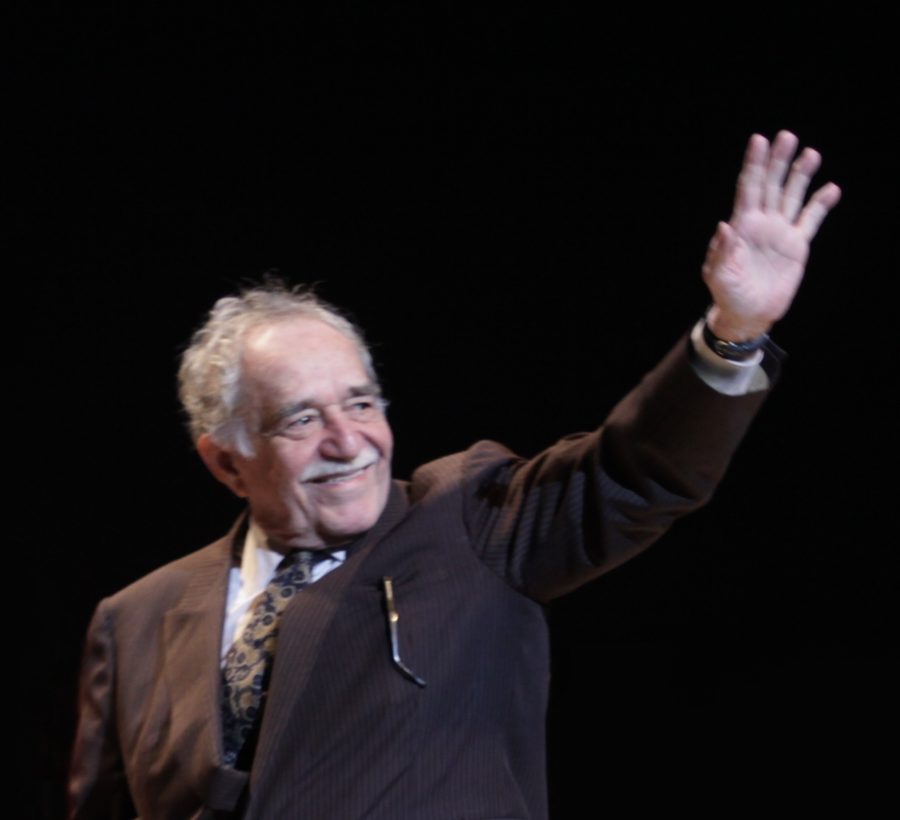

Image by Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara via Wikimedia Commons

“Our independence from Spanish domination did not put us beyond the reach of madness,” said Gabriel García Márquez in his 1982 Nobel Prize acceptance speech. García Márquez, who died yesterday at the age of 87, refers of course to all of Spain’s former colonies in Latin America and the Caribbean, from his own Colombia to Cuba, the island nation whose artistic struggle to come to terms with its history contributed so much to that art form generally known as “magical realism,” a syncretism of European modernism and indigenous art and folklore, Catholicism and the remnants of Amerindian and African religions.

While the term has perhaps been overused to the point of banality in critical and popular appraisals of Latin-American writers (some prefer Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier’s lo real maravilloso, “the marvelous real”), in Marquez’s case, it’s hard to think of a better way to describe the dense interweaving of fact and fiction in his life’s work as a writer of both fantastic stories and unflinching journalistic accounts, both of which grappled with the gross horrors of colonial plunder and exploitation and the subsequent rule of bloodthirsty dictators, incompetent patriarchs, venal oligarchs, and corporate gangsters in much of the Southern Hemisphere.

Nevertheless, it’s a description that sometimes seems to obscure García Marquez’s great purpose, marginalizing his literary vision as trendy exotica or a “postcolonial hangover.” Once asked in a Paris Review interview the year before his Nobel win about the difference between the novel and journalism, García Márquez replied, “Nothing. I don’t think there is any difference. The sources are the same, the material is the same, the resources and the language are the same.”

In journalism just one fact that is false prejudices the entire work. In contrast, in fiction one single fact that is true gives legitimacy to the entire work. That’s the only difference, and it lies in the commitment of the writer. A novelist can do anything he wants so long as he makes people believe in it.

García Márquez made us believe. One would be hard-pressed to find a 20th century writer more committed to the truth, whether expressed in dense mythology and baroque metaphor or in the dry rationalist discourse of the Western episteme. For its multitude of incredible elements, the 1967 novel for which García Márquez is best known—One Hundred Years of Solitude—captures the almost unbelievable human history of the region with more emotional and moral fidelity than any strictly factual account: “However bizarre or grotesque some particulars may be,” wrote a New York Times reviewer in 1970, “Macondo is no never-never land.” In fact, García Márquez’s novel helped dismantle the very real and brutal South American empire of banana company United Fruit, a “great irony,” writes Rich Cohen, of one mythology laying bare another: “In college, they call it ‘magical realism,’ but, if you know history, you understand it’s less magical than just plain real, the stuff of newspapers returned as lived experience.”

Edith Grossman, translator of several of García Márquez’s works—including Love in the Time of Cholera and his 2004 autobiography Living to Tell the Tale (Vivir para Cotarla)—agrees. “He doesn’t use that term at all, as far as I know,” she said in a 2005 interview with Guernica’s Joel Whitney: “It’s always struck me as an easy, empty kind of remark.” Instead, García Márquez’s style, says Grossman, “seemed like a way of writing about the exceptionalness of so much of Latin America.”

Today, in honor and with tremendous gratitude for that indefatigable chronicler of exceptional lived experience, we offer several online texts of Gabriel García Márquez’s short works at the links below.

HarperCollins’ online preview of García Marquez’s Collected Stories includes the full text of “The Third Resignation,” “The Other Side of Death,” “Eva Is Inside Her Cat,” “Bitterness for Three Sleepwalkers,” and “Dialogue with the Mirror,” all from the author’s 1972 collection Eyes of a Blue Dog (Ojos de perro azul).

At The New Yorker, you can read García Marquez’s story “The Autumn of the Patriarch” (1976) and his 2003 autobiographical essay “The Challenge.”

Follow the links below for more of García Marquez’s short fiction from various university websites:

“Death Constant Beyond Love” (1970)

“The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” (1968)

“A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” (1955)

Visit The Modern Word for an excellent biographical sketch of the author.

See The New York Times for “A Talk with Gabriel Garcia Marquez” in the year of his Nobel win, an essay in which he recounts his 1957 meeting with Ernest Hemingway, and many more reviews and essays.

Finally, we should also mention that you can download Love in the Time of Cholera or Hundred Years of Solitude for free (as audio books) if you join Audible.com’s 30-day program. We have details on it here.

As we say farewell to one of the world’s greatest writers, we can remember him not only as a writer of “magical realism,” whatever that phrase may mean, but as a teller of complicated, wondrous, and sometimes painful truths, in whatever form he happened to find them.

Related Content:

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

Read 12 Masterful Essays by Joan Didion for Free Online, Spanning Her Career From 1965 to 2013

600 Free eBooks: Download Great Books for Free

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness