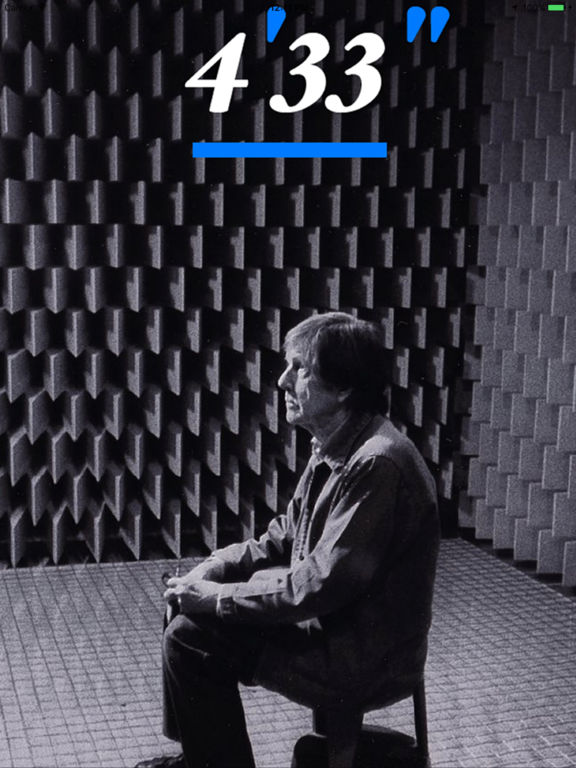

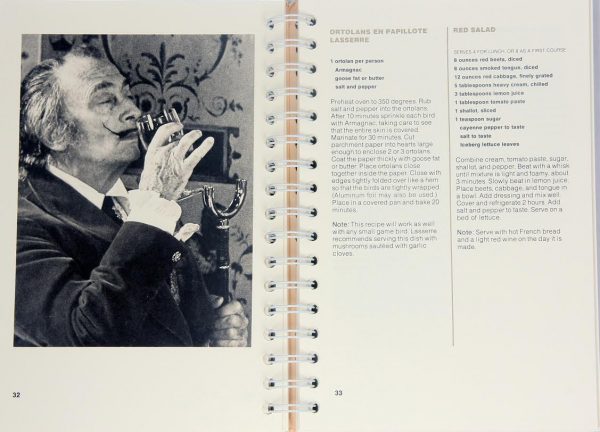

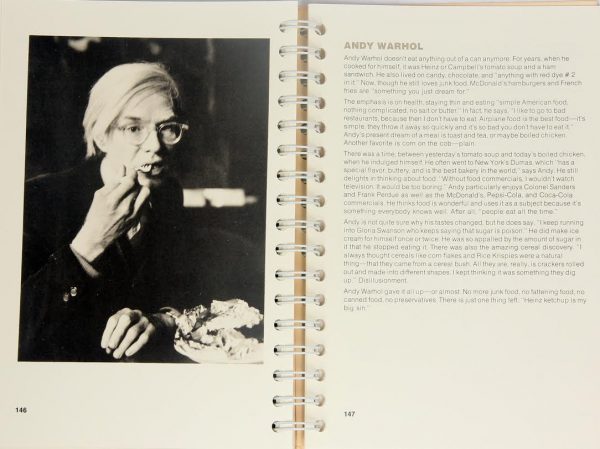

If we can consider some cooks artists, surely we can consider some artists cooks. Madeleine Conway and Nancy Kirk surely operated on that assumption when they put together The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook, which collects 155 recipes from 30 such figures not primarily known for their culinary acumen as Salvador Dalí, Willem de Kooning, Louise Bourgeois, Andy Warhol, Helen Frankenthaler, Roy Lichtenstein, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude. (“Strangely,” write the wags at Phaidon, “there are no wraps.”)

Published in 1978, the Artists’ Cookbook has long since left print, though pricey second-hand copies of the MoMA-issued edition and somewhat more affordable copies of the spiral-bound trade edition still circulate: Nick Harvill Libraries, for instance offers one for $125.

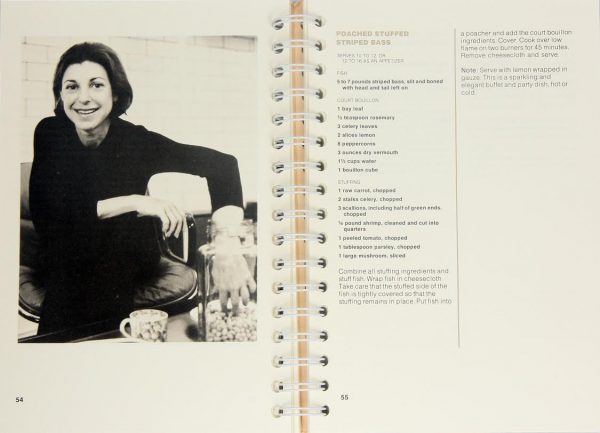

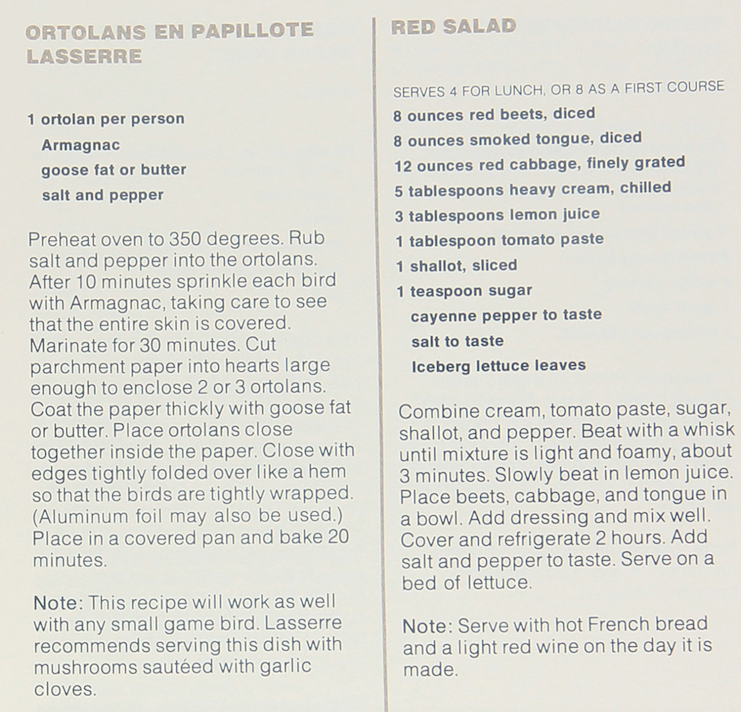

“Simplicity is a recurring theme,” says their site of the recipes contained within, which include Dalí’s red salad, de Kooning’s seafood sauce, Bourgeois’ French cucumber salad, Andy Warhol’s perhaps predictable boiling method for Campbell’s canned soup, Frankenthaler’s poached stuffed striped bass, Lichtenstein’s not entirely serious “primordial soup” (involving “8cc hydrogen” and “5cc ammonia”), and Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s complete “quick and easy filet mignon dinner party.”

Taken as a whole, the project captures not just a distinctive moment in American culture when you could publish a cookbook with pretty much any theme — we’ve previously featured Dalí’s own, which came out in 1973, and the rock-star-oriented Singers & Swingers in the Kitchen, from 1967 — but an equally distinctive moment, and place, in American art. MoMA, as you might expect, brought in the artists with whom they had the closest connections, which in the mid-1970s meant a particularly influential couple of generations who mostly rose to prominence, and stayed in prominence, in New York City.

That’s not to say that the contributors to The Museum of Modern Art Artists’ Cookbook were born into the art world. Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova quotes excerpts of the book’s interviews with the artists about their early culinary lives: Bourgeois rues the “wasted hours” spent cooking for her father (“in those days a man had the right to have his food ready for him at all times.” De Kooning recalls his childhood in poverty in Holland where, “when you had dinner, it was always brown beans.” Dalí and Warhol put their eccentricities on display, the former with his all-white table (“white porcelain, white damask, and white flowers in crystal vases”) and the latter with his declaration that “airplane food is the best food.” De gustibus, as they say in food and art alike, non disputandum est.

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

The Jean-Paul Sartre Cookbook: Philosopher Ponders Making Omelets in Long Lost Diary Entries

Alice B. Toklas Reads Her Famous Recipe for Hashish Fudge (1963)

Ernest Hemingway’s Summer Camping Recipes

Leo Tolstoy’s Family Recipe for Macaroni and Cheese

1967 Cookbook Features Recipes by the Rolling Stones, Simon & Garfunkel, Barbra Streisand & More

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.