In Carolyn Forché’s stunning new memoir, What You Have Heard is True, the poet and activist makes a sad observation about poetry in America. When it is “mentioned in the American press, if it is mentioned, the story begins with ‘Poetry doesn’t matter,’ or ‘No one reads poetry.’ No matter what is said. It doesn’t matter.”

But of course, Forché believed poetry mattered a great deal—that we need it in the struggle “against forgetting,” a phrase she took from Milan Kundera for the title of an anthology of the “poetry of witness.” Poets resist injustice and inhumanity, she says “by virtue of recuperating from the human soul its natural prayer and consciousness.”

Such a poet is Joy Harjo, newly appointed Poet Laureate in the United States, the first Native American woman to hold the post. Harjo asks us to remember—to remember especially that the grand sweep of history cannot sever us from the natural world of which we are an inextricable part, and which is itself the source of “the dance language is.”

Remember the plants, trees, animal life who all have

their

tribes, their families, their histories, too. Talk to

them,

listen to them. They are alive poems.

The stargazing, tree-hugging exhortations in “Remember” are radical statements in every sense of the word. Maybe poetry doesn’t matter much to most Americans. We cannot, as William Carlos Williams wrote, “get the news from poems,” and our hunger for fresh news is never sated. But maybe what we find in poetry is far better suited to saving our lives, offering a release, for example, from fear, as Harjo speak/sings in her charismatic performance from HBO’s Def Poetry Jam in 2002.

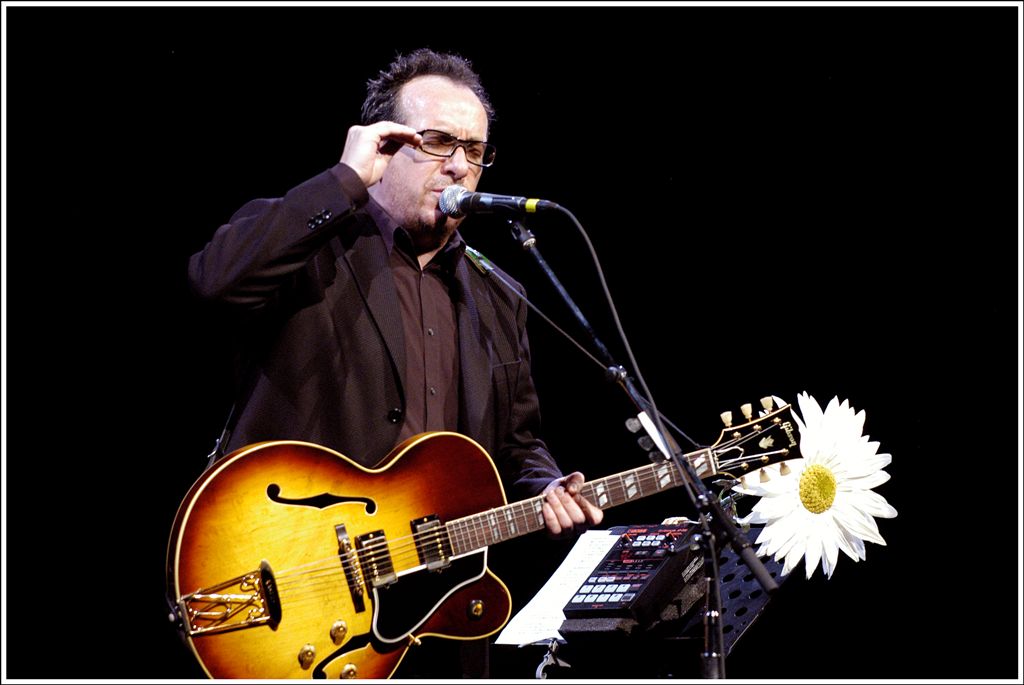

Harjo remembers the horrors her ancestors endured, and tells the fear that followed through the centuries, “I release you. You were my beloved and hated twin. But now I don’t know you as myself.” A member of the Muskoke/Creek Nation, Harjo was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1951 and earned her MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop in 1978. She went on to publish several books of poetry and nonfiction and win multiple prestigious awards while also performing poetry across the country and playing saxophone with her band Poetic Justice.

Her soulful delivery conveys a fundamentally American experience of the struggle against erasure, a struggle against power that is waged, as Kundera wrote, with the weapon of remembering. Echoing Langston Hughes, Harjo weaves the story of her community back into the country’s past and its present—a story that includes within it demands for justice that will not be forgotten. Poetry should matter far more to us than it does. But those who hear the country’s newest Laureate may find she is exactly the fearless voice we need to remind us of our unavoidable connections to the past, the earth, and our responsibilities to each other.

Harjo stopped by the Academy of American Poets this month in celebration of her appointment. Just above, see her read “An American Sunrise.” “We are still America,” she says, “We / know the rumors of our demise. We spit them out. They die / soon.”

These reading will be added to the Poetry section of our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

“PoemTalk” Podcast, Where Impresario Al Filreis Hosts Lively Chats on Modern Poetry

An 8‑Hour Marathon Reading of 500 Emily Dickinson Poems

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness