“Even in third world countries, like Senegal, it isn’t like this…”

Related Content:

The Splendid Book Design of the 1946 Edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

“Even in third world countries, like Senegal, it isn’t like this…”

Related Content:

The Splendid Book Design of the 1946 Edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

In our time, few branches of science have taken as much public abuse as quantum physics, the study of how things behave at the atomic scale. It’s not so much that people dislike the subject as they see fit to draft it in support of any given notion: quantum physics, one hears, proves that we have free will, or that Buddhist wisdom is true, or that there is an afterlife, or that nothing really exists. Those claims may or may not be true, but they do not help us at all to understand what quantum physics actually is. For that we’ll want to turn to Dominic Walliman, a Youtuber whose channel Domain of Science features clear visual explanations of scientific fields including physics, chemistry, mathematics, as well as the whole domain of science itself — and who also, as luck would have it, is a quantum physics PhD.

With his knowledge of the field, and his modesty as far as what can be definitively said about it, Wallman has designed a map of quantum physics, available for purchase at his web site. In the video above he takes us on a guided tour through the realms into which he has divided up and arranged his subject, beginning with the “pre-quantum mysteries,” inquiries into which led to its foundation.

From there he continues on to the foundations of quantum physics, a territory that includes such potentially familiar landmarks as particle-wave duality, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, and the Schrödinger equation — though not yet his cat, another favorite quantum-physics reference among those who don’t know much about quantum physics.

Alas, as c explains in the subsequent “quantum phenomena” section, Schrödinger’s cat is “not very helpful, because it was originally designed to show how absurd quantum mechanics seems, as cats can’t be alive and dead at the same time.” But then, this is a field that proceeds from absurdity, or at least from the fact that its observations at first made no sense by the traditional laws of physics. There follow forays into quantum technology (lasers, solar panels, MRI machines), quantum information (computing, cryptography, the prospect teleportation), and a variety of subfields including condensed matter physics, quantum biology, and quantum chemistry. Though detailed enough to require more than one viewing, Walliman’s map also makes clear how much of quantum physics remains unexplored — and most encouragingly of all, leaves off its supposed philosophical, or existential implications. You can watch Walliman’s other introduction to Quantum Physics below.

Related Content:

The Map of Physics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Physics Fit Together

The Map of Chemistry: New Animation Summarizes the Entire Field of Chemistry in 12 Minutes

The Map of Mathematics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Math Fit Together

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Welkom in Amsterdam… 1922.

Neural network artist Denis Shiryaev describes himself as “an artistic machine-learning person with a soul.”

For the last six months, he’s been applying himself to re-rendering documentary footage of city life—Belle Epoque Paris, Tokyo at the start of the the Taishō era, and New York City in 1911—the year of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.

It’s possible you’ve seen the footage before, but never so alive in feel. Shiryaev’s renderings trick modern eyes with artificial intelligence, boosting the original frames-per-second rate and resolution, stabilizing and adding color—not necessarily historically accurate.

The herky-jerky bustling quality of the black-and-white originals is transformed into something fuller and more fluid, making the human subjects seem… well, more human.

This Trip Through the Streets of Amsterdam is truly a blast from the past… the antithesis of the social distancing we must currently practice.

Merry citizens jostle shoulder to shoulder, unmasked, snacking, dancing, arms slung around each other… unabashedly curious about the hand-cranked camera turned on them as they go about their business.

A group of women visiting outside a shop laugh and scatter—clearly they weren’t expecting to be filmed in their aprons.

Young boys looking to steal the show push their way to the front, cutting capers and throwing mock punches.

Sorry, lads, the award for Most Memorable Performance by a Juvenile goes to the small fellow at the 4:10 mark. He’s not hamming it up at all, merely taking a quick puff of his cigarette while running alongside a crowd of men on bikes, determined to keep pace with the camera person.

Numerous YouTube viewers have observed with some wonder that all the people who appear, with the distant exception of a baby or two at the end, would be in the grave by now.

They do seem so alive.

Modern eyes should also take note of the absences: no cars, no plastic, no cell phones…

And, of course, everyone is white. The Netherlands’ population would not diversify racially for another couple of decades, beginning with immigrants from Indonesia after WWII and Surinam in the 50s.

With regard to that, please be forewarned that not all of the YouTube comments have to do with cheeky little boys and babies who would be pushing 100…

The footage is taken from the archival collection of the EYE filmmuseum in Amsterdam, with ambient sound by Guy Jones.

See more of Denis Shiryaev’s upscaled vintage footage in the links below.

Related Content:

Watch Vintage Footage of Tokyo, Circa 1910, Get Brought to Life with Artificial Intelligence

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

The story of popular music in the late 20th century is never complete without an account of the explosive psychedelic rock, funk, Afrobeat, and other hybrid styles that proliferated on the African continent and across Latin American and the Caribbean in the 1960s and 70s. It’s only lately, however, that large audiences are discovering how much pioneering music came out of Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and other postcolonial countries, thanks to UK labels like Strut and Soundway (named by The Guardian as “one of the 10 British Labels defining the sound of 2014” and named “Label of the Year” in 2017).

Germany’s Analogue Africa, a label that reissues classic albums from the era, puts it this way: “the future of music happened decades ago.” Only most Western audiences weren’t paying attention—with notable exceptions, of course: superstar drummer Ginger Baker apprenticed himself to Fela Kuti and became an evangelist for African drumming; Brian Eno and Talking Heads’ David Byrne (who also introduced thousands to “world music”) imported the sound of African rock to New Wave in the 80s, as did post-punk bands like Orange Juice and others in Britain, where music from Africa generally had a bigger impact.

But the fusion of African polyrhythms with rock instruments and song structures had been done, and done incredibly well, already by dozens of bands, including several in the East African country of Zambia, which had been British-controlled Northern Rhodesia until its independence in 1964. In the decade after, bands formed around the country to create a unique form of music known as “Zamrock,” as it came to be called, “forged by a particular set of national circumstances,” writes Calum MacNaughton at Music in Africa.

Zamrock bands were influenced by the funk and soul of James Brown and the heavy rock of Hendrix, Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, The Who, and Cream—the same music everyone else was listening to. As Rikki Ililonga from the band Musi-O-Tunya says in the Vinyl Me, Please mini-documentary above, says, “the hippie time, the flowers, love and everything, Woodstock. We were a part of that culture too. If the record was in the Top 10 in the UK, it was in the Top 10 here.” But Zambia had its own concerns, and its own powerful musical traditions.

“As much as we wanted to play rock from the Western world, we are Africans,” says Jagari Chanda, vocalist for a band called WITCH (“we intend to cause havoc”), “so the other part is from Africa—Zambia. So it’s Zambian type of rock—Zamrock.” The term was coined by Zambian DJ Manasseh Phiri. The music itself “was the soundtrack of Kenneth Kaunda’s socialist ideology of Zambian Humanism,” MacNaughton notes. “In fact, Zamrock owed much of its existence to the nation’s first president and founding father. A guitar-picker who took great pleasure in song” and who promoted local music “via a quota system” imposed on the newly-formed Zambia Broadcasting Service (ZBS).

Vinyl Me, Please has collaborated with MacNaughton and others from Now-Again Records to release 8 Zamrock albums, “7 of which have never been reissued in their original form.” The video above, “The Story of Zamrock,” reflects their decade-long journey to rediscover the 70s scene and its pioneers. In the video at the top from Bandsplaining, you can learn more about Zamrock, which has been gaining prominence in album reissues for the last several years, and which “deserves to be a part of the musical history of Africa in a much bigger way than it has been up to now,” Henning Goranson Sandberg writes at The Guardian. See all of the music featured in the video at the top in the tracklist below.

0:00 WITCH — “Living In The Past”

0:40 Keith Mlevhu — “Love and Freedom”

1:05 Paul Ngozi — “Bamayo”

3:11 WITCH — “Introduction”

4:19 Musi-O-Tunya — “Mpondolo”

4:32 Musi-O-Tunya — “Dark Sunrise”

5:28 Rikki Ililonga — “Sheebeen Queen”

5:37 WITCH — “Lazy Bones”

6:00 Paul Ngozi — “Anasoni”

6:16 The Peace — “Black Power”

6:46 Keith Mlevhu — “Ubuntungwa”

7:06 Amanaz — “Khala my Friend”

7:24 WITCH — “Living In The Past”

8:19 The Blackfoot — “When I Needed You”

8:39 Salty Dog — “See The Storm”

9:30 Salty Dog — “Fast”

10:42 Rikki Ililonga & Derick Mbao — “Madzi A Moyo”

10:54 Paul Ngozi — “Nshaupwa Bwino”

11:43 Amanaz — “Sunday Morning”

12:38 The Blackfoot — “Lonley Highway”

Related Content:

Stream 8,000 Vintage Afropop Recordings Digitized & Made Available by The British Library

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

You can’t take it with you if you’ve got nothing to take with you.

Once upon a time, the now-empty Great Pyramid of Giza was sumptuously appointed inside and out, to ensure that Pharaoh Khufu, or Cheops as he was known to the Ancient Greeks, would be well received in the afterlife.

Bling was a serious thing.

Thousand of years further on, cinematic portrayals have us convinced that tomb raiders were greedy 19th- and 20th-century curators, eagerly filling their vitrines with stolen artifacts.

There’s some truth to that, but modern Egyptologists are fairly convinced that Khufu’s pyramid was looted shortly after his reign, by opportunists looking to grab some goodies for their journey to the afterlife.

At any rate, it’s been picked clean.

Perhaps one day, we 21st-century citizens can opt in to a pyramid experience akin to Rome Reborn, a digital crutch for our feeble imagination to help us past the empty sarcophagus and bare walls that have defined the world’s oldest tourist attraction’s interiors for … well, not quite ever, but certainly for Flaubert, Mark Twain, and 12th-century scholar Abd al-Latif.

Fast forwarding to 2017, the BBC’s Rajan Datar hosted “Secrets of the Great Pyramid,” a podcast episode featuring Egyptologist Salima Ikram, space archaeologist Dr Sarah Parcak, and archaeologist, Dr Joyce Tyldesley.

The experts were keen to clear up a major misconception that the 4600-year-old pyramid was built by aliens or enslaved laborers, rather than a permanent staff of architects and engineers, aided by Egyptian civilians eager to barter their labor for meat, fish, beer, and tax abatement.

Datar’s question about a scanning project that would bring further insight into the Pyramid of Giza’s construction and layout was met with excitement.

This attraction, old as it is, has plenty of new secrets to be discovered.

We’re happy to share with you, readers, that 3 years after that episode was taped, the future is here.

The scanning is complete.

Witness the BBC’s 360° tour inside the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Use your mouse to crane your neck, if you like.

As of this writing, you could tour the pyramid in person, should you wish—the usual touristic hoards are definitely dialed down.

But, given the contagion, perhaps better to tour the King’s Chamber, the Queen’s Chamber, and the Grand Gallery virtually, above.

(An interesting tidbit: the pyramid was more distant to the ancient Romans than the Colosseum is to us.)

Listen to the BBC’s “Secrets of the Great Pyramid” episode here.

Tour the Great Pyramid of Giza here.

Related Content:

How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

When it came out in 1927, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showed audiences the kind of wholly invented reality, hitherto beyond imagination, that could be realized in motion pictures. Its vision of a society bisected into colossal skyscrapers and underground warrens, an industrial Art Deco dystopia, continues to influence filmmakers today. This despite — or perhaps because of — the simple story it tells, in which Freder, the scion of the city of Metropolis, rebels against his father after following Maria, a good-hearted maiden from the underclass, into the infernal lower depths.

In the role of Maria was a then-unknown 18-year-old actress named Brigitte Helm. “For all the steam and special effects,” writes Robert McG. Thomas Jr. in Helm’s New York Times obituary, “for many who have seen the movie in its various incarnations, including a tinted version and one accompanied by music, the most compelling lingering image is neither the towers above nor the hellish factories below. It is the startling transformation of Ms. Helm from an idealistic young woman into a barely clad creature performing a lascivious dance in a brothel.”

Halfway through the film, Maria gets kidnapped by the villainous inventor Rotwang and cloned as a robot. It is this robot, not the real Maria, who takes the stage in the scene in question, practically nude by the standards of silent-era cinema. Lang used the sequence to push not just the bounds of propriety, but the aesthetic capabilities of his art form: viewers would never have seen anything like the frame-filling field of eyeballs into which the slavering crowd of tuxedoed men dissolve. Here we have a medium demonstrating decisively and powerfully what sets it apart from all others, in just one of the scenes restored only recently to its original form.

When Thomas alluded to the many extant cuts of Metropolis in his 1996 obituary for Helm, the now-definitive version of the picture that made her a star still lay in the future. 2010’s The Complete Metropolis includes material rediscovered just two years before, on a 16-millimeter reduction negative stored at Buenos Aires’ Museo del Cine and long forgotten thereafter. Now, just as Lang intended us to, we can behold his cinematic vision of rulers employing the highest technology to keep even the elite mesmerized by titillating spectacles — a fantastical scenario that has nothing at all to do, of course, with the future as it actually turned out.

Related Content:

Metropolis: Watch a Restored Version of Fritz Lang’s Masterpiece (1927)

Read the Original 32-Page Program for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang Invents the Video Phone in Metropolis (1927)

H.G. Wells Pans Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in a 1927 Movie Review: It’s “the Silliest Film”

10 Great German Expressionist Films: From Nosferatu to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Watch After the Ball, the 1897 “Adult” Film by Pioneering Director Georges Méliès (Almost NSFW)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

You may know his name, and you definitely know the iconic photo of him standing next to Tommie Smith and Peter Norman on the medals podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, his black-gloved fist raised next to Smith’s in defiance of racial injustice. But you may know little more about John Carlos. Many of us learned about him the same way students at a Southern California high school, where he worked as a counselor after retiring from running, did: “Man, we see this picture in the history book and they don’t have any story about it,” he remembers some kids telling him. “It’s just a two-liner with the people’s names.”

The Vox Darkroom video above packs more than a caption version of his history in just under 10 minutes. The silent protest, we learn, followed a threatened boycott from the athletes earlier in the year, supported by Martin Luther King, Jr., who appears in a clip. Instead, they went on to win medal after medal. We also learn much more about how all three runners on the podium, including Silver-winning Aussie Peter Norman, participated by wearing buttons supporting the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Founded by former athlete and activist Harry Edwards, the organization aimed to strategically disrupt U.S. Olympic success by “opting out of the games,” refusing to give Black athletes’ labor to sports that refused to combat racism.

Twenty years before these actions, Black athletes became potent symbols of the bootstrapping American success story for the media, long before the end of legal segregation. As history professor Dexter Blackman says in the video, the message became, “if Jackie Robinson can make it, then why can’t other Blacks make it?” This “myth of racial progress” could not survive the 1960s. By the time of Smith and Carlos’ arrival in Mexico City in October of 1968, Martin Luther King had been assassinated. Cities around the country were erupting as frustration over failed Civil Rights efforts boiled over. Neither Carlos nor Smith wear shoes in their podium photo, in protest of the poverty that persisted in Black communities.

The three paid a price for their statement. The protest was called “a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit” by the IOC president, who had not objected to Nazi salutes when he had been an Olympic official in 1936. Norman, who seems completely oblivious at first glance in the photograph, “returned home to Australia a pariah,” CNN writes, “suffering unofficial sanction and ridicule as the Black Power salute’s forgotten man. He never ran in the Olympics again.” Smith fared better, though he was suspended with Carlos from the Olympic team. He left running, played NFL football, won several awards and commendations, and became a track coach and sociology professor at Oberlin.

In an essay at Vox, Carlos describes how “the mood in the stadium went straight to venom” after the two raised their fists. “The first 10 years after those Olympics were hell for me. A lot of people walked away from me…. they were afraid. What they saw happening to me, they didn’t want it to happen to them and theirs.” His kids, he said “were tormented,” his marriage “crumbled.” Still, he would do it again. Carlos embodies the same uncompromising attitude, one that refuses to silently accept racism, even while standing (or kneeling) in silence. “If you’re famous and you’re black,” he writes, “you have to be an activist. That’s what I’ve tried to do my whole life.”

Related Content:

Muhammad Ali Gives a Dramatic Reading of His Poem on the Attica Prison Uprising

How Jazz Helped Fuel the 1960s Civil Rights Movement

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

There are too many competing stories to tell about the pandemic for any one to take the spotlight for long, which makes coming to terms with the moment especially challenging. Everything seems in upheaval—especially in parts of the world where rampant corruption, ineptitude, and authoritarian abuse have worsened and prolonged an already bad situation. But if there’s a lens that might be wide enough to take it all in, I’d wager it’s the story of food, from manufacture, to supply chains, to the table.

The ability to dine out serves as a barometer of social health. Restaurants are essential to normalcy and neighborhood coherence, as well as hubs of local commerce. They now struggle to adapt or close their doors. Food service staff represent some of the most precarious of workers. Meanwhile, everyone has to eat. “Some of the world’s best restaurants have gone from fine dining to curbside pickups,” writes Rico Torres, Chef and Co-owner of Mixtli. “At home, a renewed sense of self-reliance has led to a resurgence of the home cook.”

Some, amateurs and professionals both, have returned their skills to the community, cooking for protestors on the streets, for example. Others have turned a newfound passion for cooking on their families. Whatever the case, they are all doing important work, not only by feeding hungry bellies but by engaging with and transforming culinary traditions. Despite its essential ephemerality, food preserves memory, through the most memory-intensive of our senses, and through recipes passed down for generations.

Recipe collections are also sites of cultural exchange and conflict. Such has been the case in the long struggle to define the essence of authentic Mexican food. You can learn more about that argument in our previous post on a collection of traditional (and some not-so-traditional) Mexican cookbooks which are being digitized and put online by researchers at the University of Texas San Antonio (UTSA). Their collection of over 2,000 titles dates from 1789 to the present and represents a vast repository of knowledge for scholars of Mexican cuisine.

But let’s be honest, what most of us want, and need, is a good meal. It just so happens, as chefs now serving curbside will tell you, that the best cooking (and baking) learns from the cooking of the past. In observance of the times we live in, the UTSA Libraries Special Collections has curated many of the historic Mexican recipes in their collection as what they call “a series of mini-cookbooks” titled “Recetas: Cocindando en los Tiempos del Coronavirus.”

Because many in our communities have found themselves in the kitchen during the COVID-19 pandemic during stay-at-home orders, we hope to share the collection and make it even more accessible to those looking to explore Mexican cuisine.

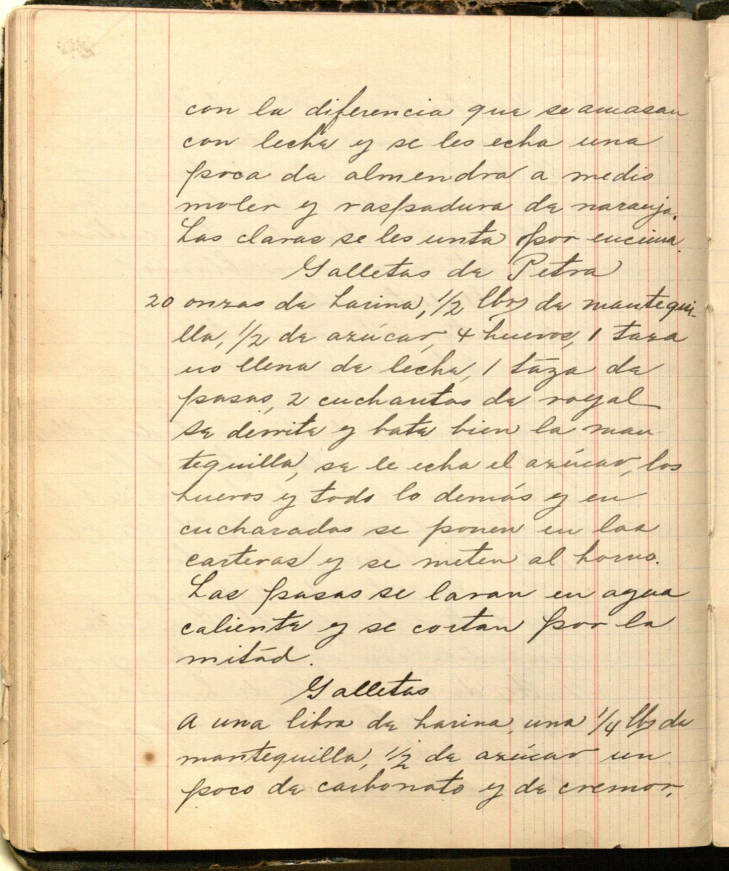

These recipes, now being made available as e‑cookbooks, have been transcribed and translated from handwritten manuscripts by archivists who are passionate about this food. Perhaps in honor of Laura Esquivel’s Like Water for Chocolate—whose novel “paints a narrative of family and tradition using Mexico’s deep connection to cuisine”—the collection has “saved the best for first” and begun with the dessert cookbook. They’ll continue the reverse order with Volume 2, main courses, and Volume 3, appetizers & drinks.

Endorsed by Chef Torres, the first mini-cookbook modernizes and translates the original Spanish into English, and is available in pdf or epub. It does not modernize more traditional ways of cooking. As the Preface points out, “many of the manuscript cookbooks of the early 19th century assume readers to be experienced cooks.” (It was not an occupation undertaken lightly.) As such, the recipes are “often light on details” like ingredient lists and step-by-step instructions. As Atlas Obscura notes, the recipe above for “ ‘Petra’s cookies’ calls for “‘one cup not quite full of milk.’ ”

“We encourage you to view these instructions as opportunities to acquire an intuitive feel for your food,” the archive writes. It’s good to learn new habits. Whatever else it is now—community service, chore, an exercise in self-reliance, self-improvement, or stress relief—cooking is also creating new ways of remembering and connecting across new distances of time and space, working with the raw materials we have at hand. Download the first Volume of the UTSA cookbook series, Postres: Guardando Lo Mejor Para el Principio, here and look for more “Cooking in the Time of Coronavirus” recipes coming soon.

Related Content:

An Archive of Handwritten Traditional Mexican Cookbooks Is Now Online

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness