If you’ve ever played Call of Cthulhu, the tabletop role-playing game based on the writing of H.P. Lovecraft, you’ve felt the frustration of having character after painstakingly-created character go insane or simply drop dead upon catching a glimpse of one of the many horrific beings infesting its world. But as the countless readers Lovecraft has posthumously accumulated over nearly eighty years know, that just signals faithfulness to the source material: Lovecraft’s characters tend to run into the same problem, living, as they do, in what French novelist Michel Houellebecq (one of his notable fans, a group that also includes Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and Jorge Luis Borges) calls “an open slice of howling fear.”

Read enough of Lovecraft’s middle-class east-coast professional narrators’ mortal struggles for the words to convey what he called “the boundless and hideous unknown” that suddenly confronts them, and you start to wonder what these creatures actually look like. The clearest word-picture comes in the 1928 story “The Call of Cthulhu,” whose narrator describes the titular ancient malevolence—avoiding instantaneous mental breakdown by looking at an idol rather than the being itself—as “a monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind.”

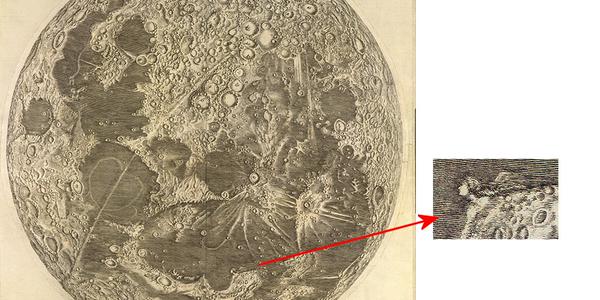

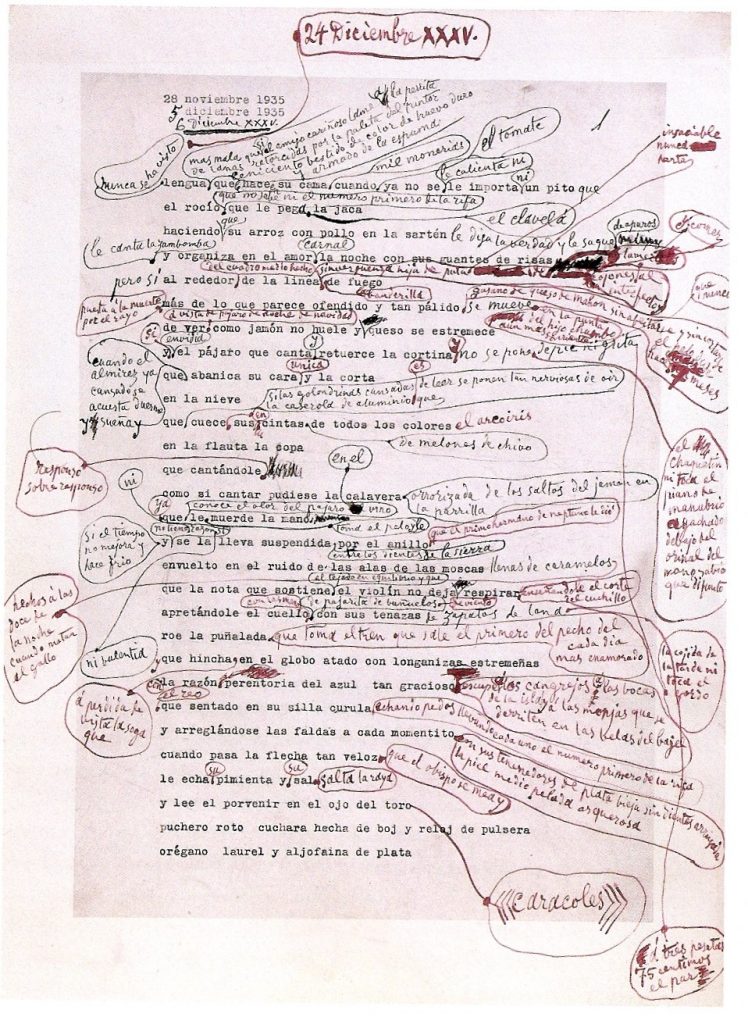

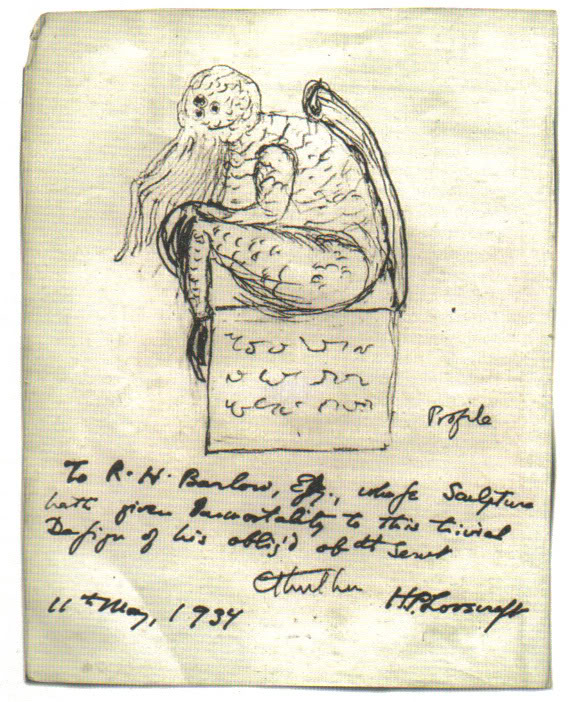

And so modern Lovecraftians have enjoyed a new variation of that giant octopus-dragon-man form on “Cthulhu for President” shirts each and every election year. (You can find one for 2016 here.) While that phenomenon would surely have surprised Lovecraft himself, constantly and fruitlessly as he struggled in life, I like to think he’d have approved of the designs, which align in fearsome spirit with the sketches he made. At the top of the post you can see one sketch of the Cthulhu idol, drawn in 1934 on a piece of correspondence with writer R.H. Barlow, Lovecraft’s friend and the eventual executor of his estate.

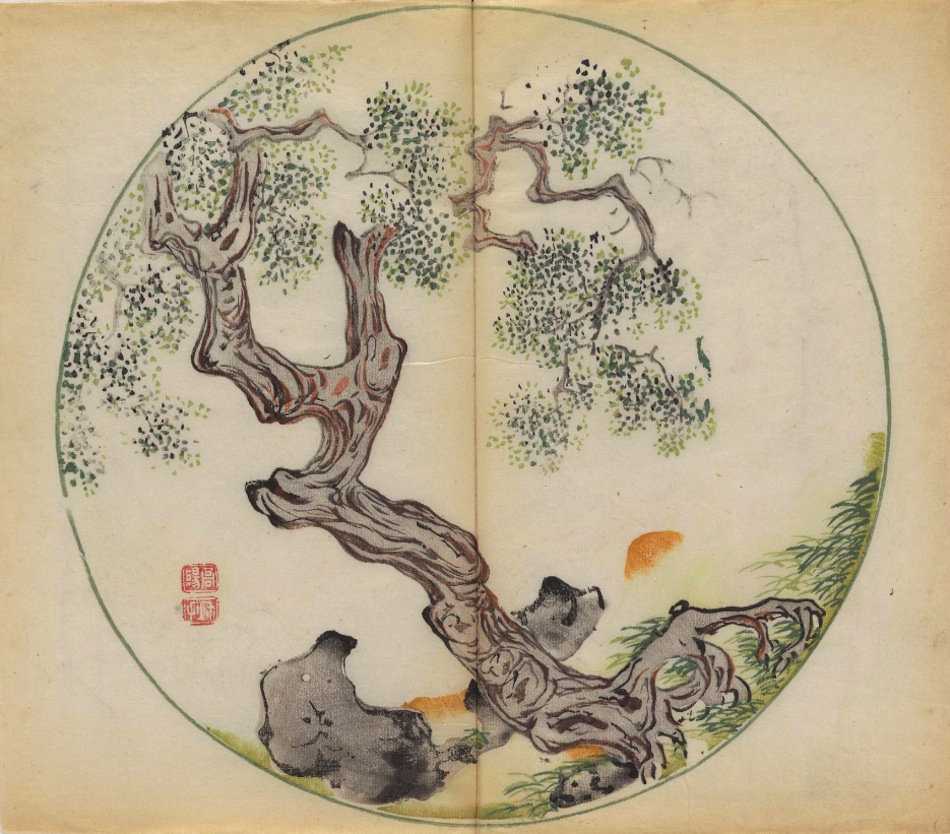

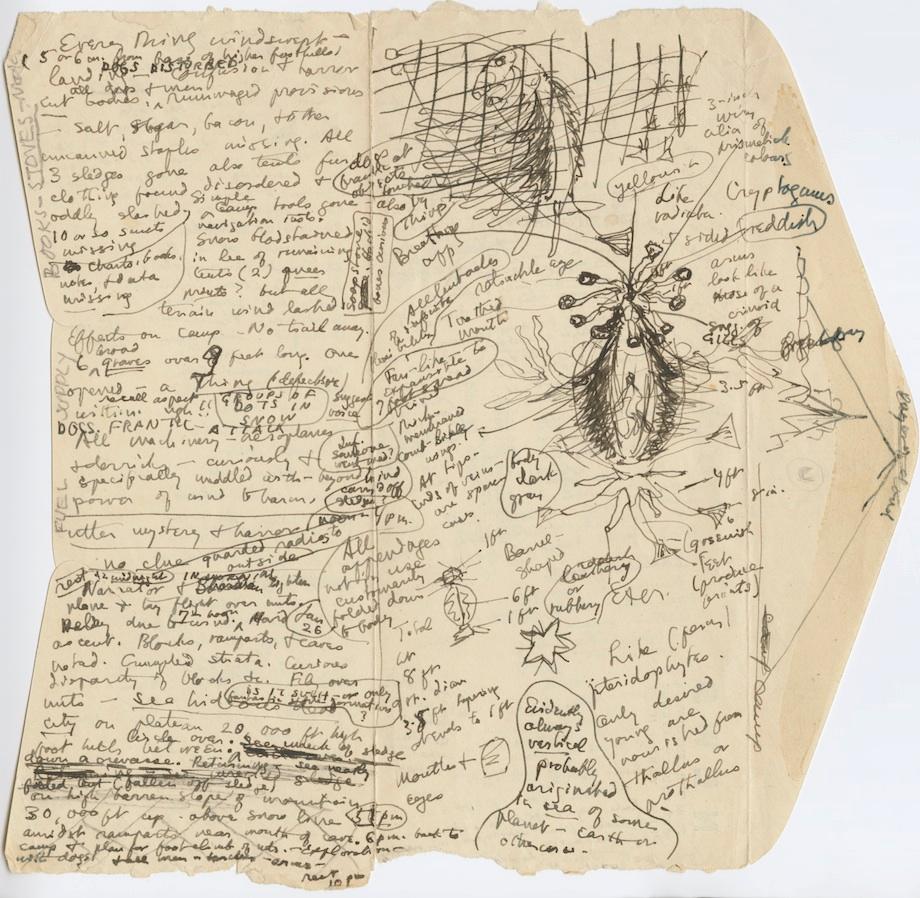

If “The Call of Cthulhu” ranks as Lovecraft’s best-known work, his 1936 novella At the Mountains of Madness surely comes in a close second. Just above, we have an illustrated page of the writer’s plot notes for this unforgettable cautionary tale of an Antarctic expedition that happens disastrously upon the mind-bending ruins of a city previously thought only a myth – and the monsters that inhabit it. It exemplifies the defining quality of Lovecraft’s mythology, where, as Slate’s Rebecca Onion puts it, “ancient beings of profound malevolence lurk just below the surface of the everyday world.”

“Mountains featured several species of forgotten, intelligent beings, including the ‘Elder Things.’ The sketch on the right side of this page of notes (click here to view it in a larger format), with its annotations (‘body dark grey’; ‘all appendages not in use customarily folded down to body’; ‘leathery or rubbery’) represents Lovecraft working out the specifics of an Elder Thing’s anatomy.” That such things lurked in Lovecraft’s imagination have made his state of mind a subject of decades and decades of rich discussion among his enthusiasts. But just the body count racked up by Cthulhu, the Elder Things, and the other denizens of this unfathomable realm should make us thankful that Lovecraft saw them in his mind’s eye so we wouldn’t have to.

Note: The second image on this page was featured in the 2013 exhibition held at Brown University, “The Shadow Over College Street: H. P. Lovecraft in Providence.” The Brown University Library is the home to the largest collection of H. P. Lovecraft materials in the world.

Related Content:

H.P. Lovecraft Gives Five Tips for Writing a Horror Story, or Any Piece of “Weird Fiction”

H.P. Lovecraft Highlights the 20 “Types of Mistakes” Young Writers Make

H.P. Lovecraft’s Classic Horror Stories Free Online: Download Audio Books, eBooks & More

Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown (Free Documentary)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.