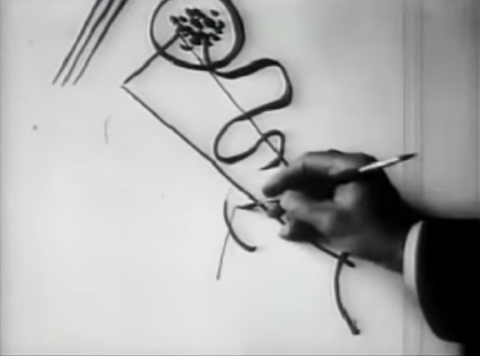

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to travel back in time and look over the shoulder of one of the early 20th century’s greatest artists to watch him work? In this brief film from 1926, we get to see the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky as he turns a blank canvas into one of his distinctive abstract compositions.

The film was made at the Galerie Neumann-Nierendorf in Berlin by Hans Cürlis, a pioneer in the making of art documentaries. At the time the film was made Kandinsky was teaching at the Bauhaus. It was the same year he published his second major treatise, On Point and Line to Plane. The contrasting straight lines and curves that Kandinsky paints in the movie are typical of this period, when his approach was becoming less intuitive and more consciously geometric.

Kandinsky believed that an artist could reach deeper truths by dispensing with the depiction of external objects and by looking within, and despite his analytic turn at the Bauhaus he continued to speak of art in deeply mystical terms. In On Point and Line to Plane, Kandinsky writes:

The work of Art mirrors itself upon the surface of our consciousness. However, its image extends beyond, to vanish from the surface without a trace when the sensation has subsided. A certain transparent, but defininite glass-like partition, abolishing direct contact from within, seems to exist here as well. Here, too, exists the possibility of entering art’s message, to participate actively, and to experience its pulsating life with all one’s senses.

Related content:

The Inner Object: Seeing Kandinsky

Vintage Footage of Picasso and Jackson Pollock Painting … Through Glass