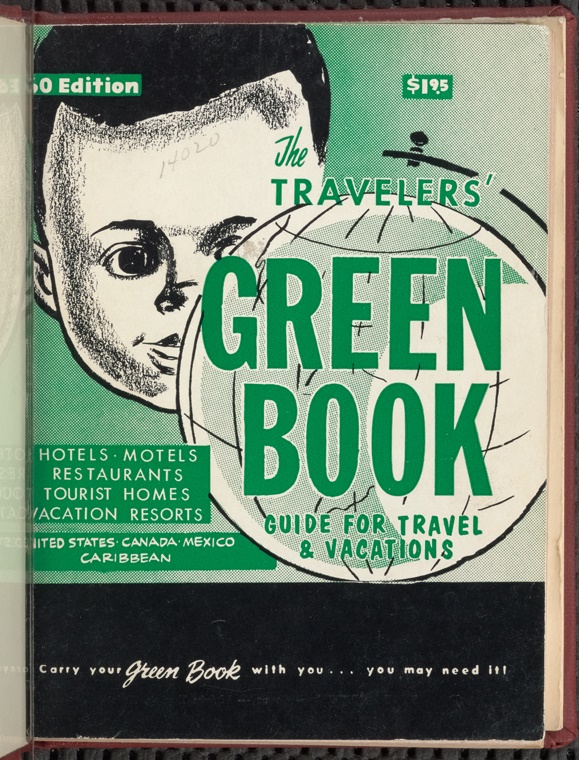

Popular entertainment has romanticized the idea of the road trip as a wholly spontaneous adventure, but for mid-century African American motorists, planning was essential. The lodgings, restaurants, and tourist attractions where they could be assured of a warm welcome were often few and far between in the era of segregation.

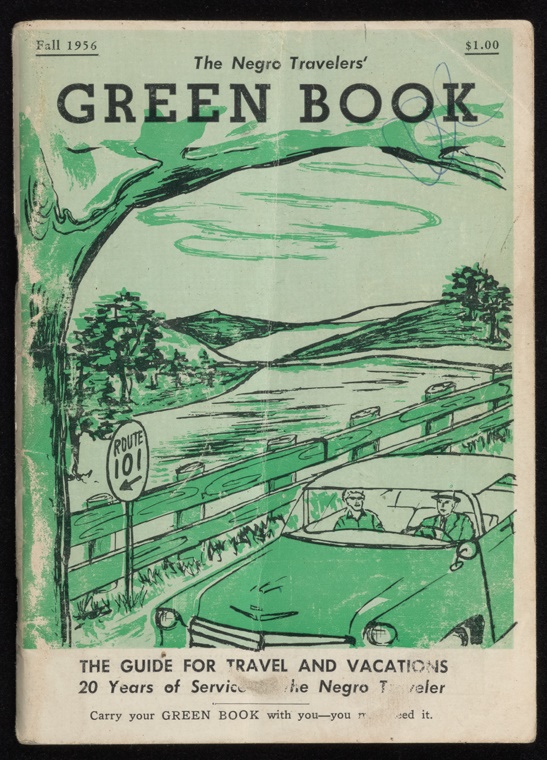

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, first printed in 1936, was an invaluable resource for travelers of color, particularly when their route took them outside of urban areas. In the pre-Internet age, publisher Victor Green, a Harlem-dwelling mailman, relied on readers to supply feedback and new locations for subsequent editions:

There are thousands of first class business places that we don’t know about and can’t list, which would be glad to serve the traveler, but it is hard to secure listings of these places since we can’t secure enough agents to send us the information. Each year before we go to press the new information is included in the new edition. When you are traveling please mention the Green Book, in order that they might know how you found their place of business, as they can see that you are strangers. If they haven’t heard about this guide, ask them to get in touch with us so that we might list their place. If this guide has proved useful to you on your trips, let us know. If not, tell us also as we appreciate your criticisms and ideas in the improvement of this guide from which you benefit. There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment. But until that time comes we shall continue to publish this information for your convenience each year.

- from the introduction to the 1949 edition

The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has digitized 21 volumes of its Green Book collection for your browsing pleasure. It’s a trip back in time.

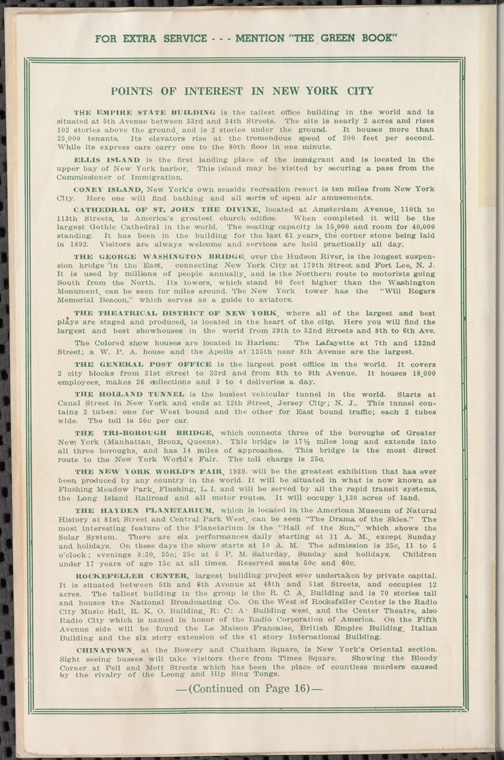

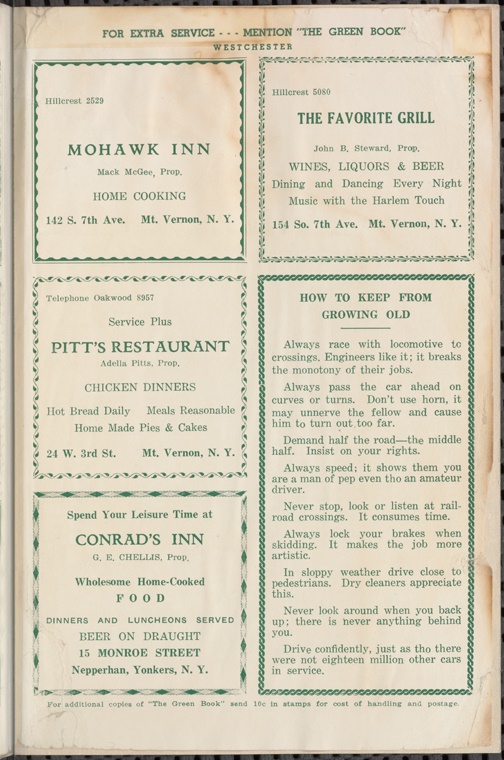

1936’s premier edition is geared toward visitors spending time in and around New York City. In appearance, it resembles a church bulletin or community theater program, with business card ads for beauty salons specializing in marcel waving and restaurants serving Southern home cooking. Publisher Green extols the wonders of Coney Island, Chinatown, and the Theatrical District, even as he notes that “the colored show houses are in Harlem.” He also seeks to give readers a laugh with “How to Keep From Growing Old,” a driver-specific list that could be read aloud from the passenger seat for the merriment of everyone in the car. (“In sloppy weather, drive close to pedestrians. Dry cleaners appreciate this.”)

The Green Book soon swelled to include national listings, as tourists and business travelers heeded Green’s call to beef up the info.

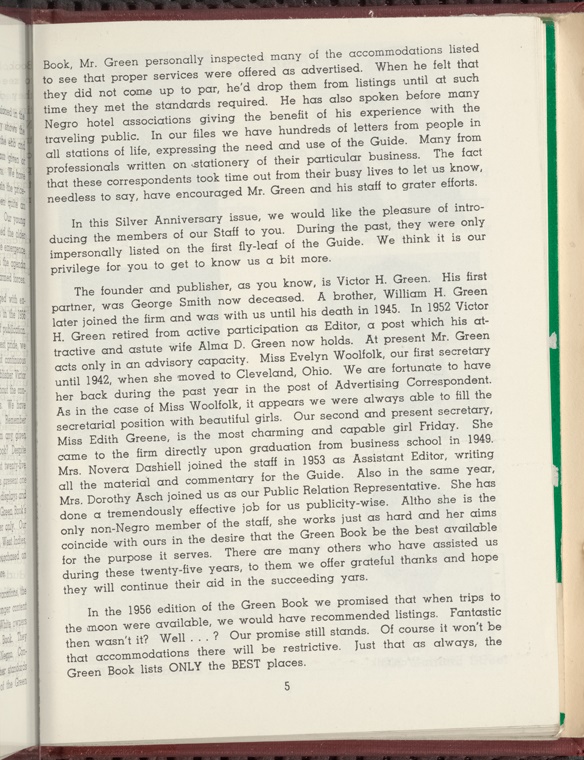

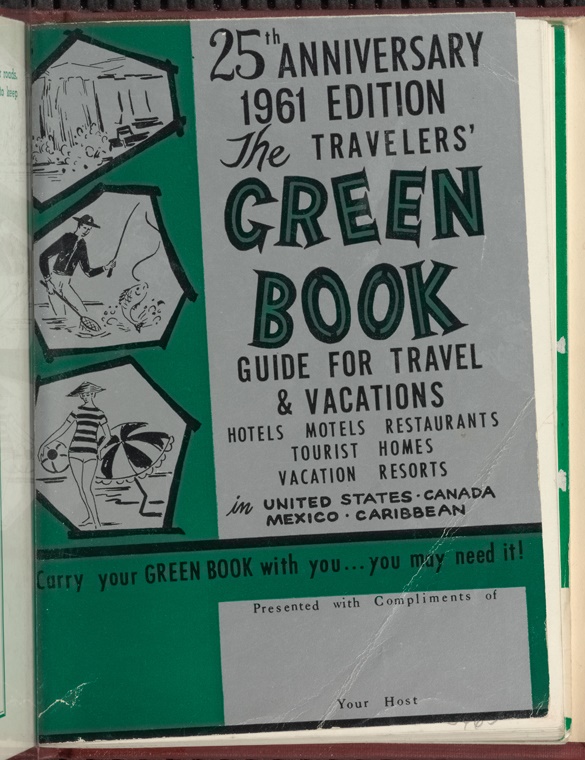

1961’s 25th anniversary edition includes a history of the enterprise, a fair amount of typos, newsy updates on the staff, and a renewed promise to list the best places on the moon, should lunar travel become an option.

Armchair travelers can take the NYPL’s digitized collection out for a spin by entering coordinates into a mapping feature for 1947 or 1956.

Starting in my Indiana hometown with sights set on Manhattan took me to the Cottage Restaurant in Columbus, Ohio, the Jones Restaurant in Grafton, West Virginia, and the beautifully named Trott Inn in Philadelphia, before I finally lay my virtual head at the America Hotel. (These days, it would be the Millennium Broadway.)

Enjoy your trip. In the words of Victor Green, “let’s all get together and make motoring better.”

Related Content:

Robert Penn Warren Archive Brings Early Civil Rights to Life

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She documented her misadventures on the road in No Touch Monkey! And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late Follow her @AyunHalliday