The first-time reader of a story called “The Nose” may expect any number of things: a character with a keen sense of smell; a murder evidenced by the titular organ, disembodied; a broader ironic point about the things right in front of our faces that we somehow never see. But given its conception in the imagination of Nikolai Gogol, “The Nose” is about a nose — a nose that, on its own, lives, breathes, walks, and dresses in finery. The nose does this, it seems, in order to rise in rank past that of its former owner, the run-of-the-mill St. Petersburg civil servant Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov.

Written in 1835 and 1836, “The Nose” satirizes the long era in Imperial Russia after Peter the Great introduced the Table of Ranks. Meant to usher in a kind of proto-meritocracy, that system assigned rank to military and government officers according, at least in theory, to their ability and achievements. The fact that those who attained high enough ranks would rise the to the level of hereditary nobles created an all-out status war across many sections of society — a war, to the mind of Gogol the master observer of bureaucracy, that could pit a man not just against his colleagues and friends but against his own body parts.

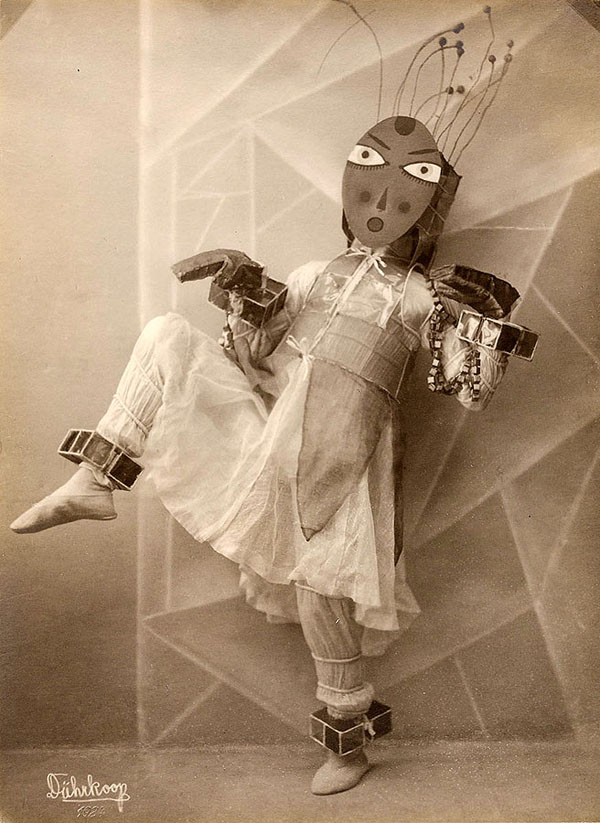

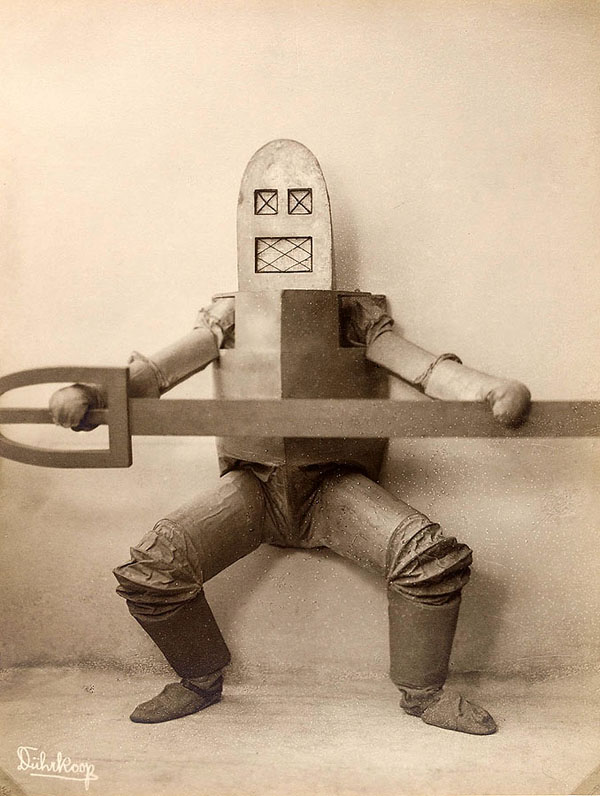

Nearly a century after the story’s publication, a young Dmitri Shostakovich took it upon himself to adapt “The Nose” into his very first opera. In collaboration with Alexander Preis, Georgy Ionin, and Yevgeny Zamyatin (author of the enduring dystopian novel We), the composer rendered even more outrageously this tale of a nose gone rogue. Incorporating pieces of Gogol’s other stories like the “The Overcoat” and “Diary of a Madman” as well as the play Marriage and the diary Dead Souls — not to mention the writings of other Russian masters, including Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov — the 1928 opera combines a wide variety of musical styles both traditional and experimental, and among its set pieces includes a number performed by giant tap-dancing noses.

You can see that part performed in the video above. The venue is London’s Royal Opera House, the director is Barrie Kosky of Berlin’s Komische Oper, and the year is 2016, half a century after The Nose’s revival. Though completed in the late 1920s, it didn’t premiere on stage in full until 1930, when Soviet censorship concentrated its energies on quashing such non-revolutionary spectacles. It wouldn’t be staged again in the Soviet Union until 1974, nearly a decade after its premiere in the United States. (Just a couple years before, Alexander Alexeieff and Claire Parker had adapted the story into the pinscreen animation previously featured here on Open Culture.) The sociopolitical concerns of Gogol’s early 19th century and Shostakovich’s early 20th may have passed, but the appeal of the former’s sharp satire — and the sheer Pythonesque weirdness of the latter’s operatic sensibility — certainly haven’t.

Related Content:

Revered Poet Alexander Pushkin Draws Sketches of Nikolai Gogol and Other Russian Artists

George Saunders’ Lectures on the Russian Greats Brought to Life in Student Sketches

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.