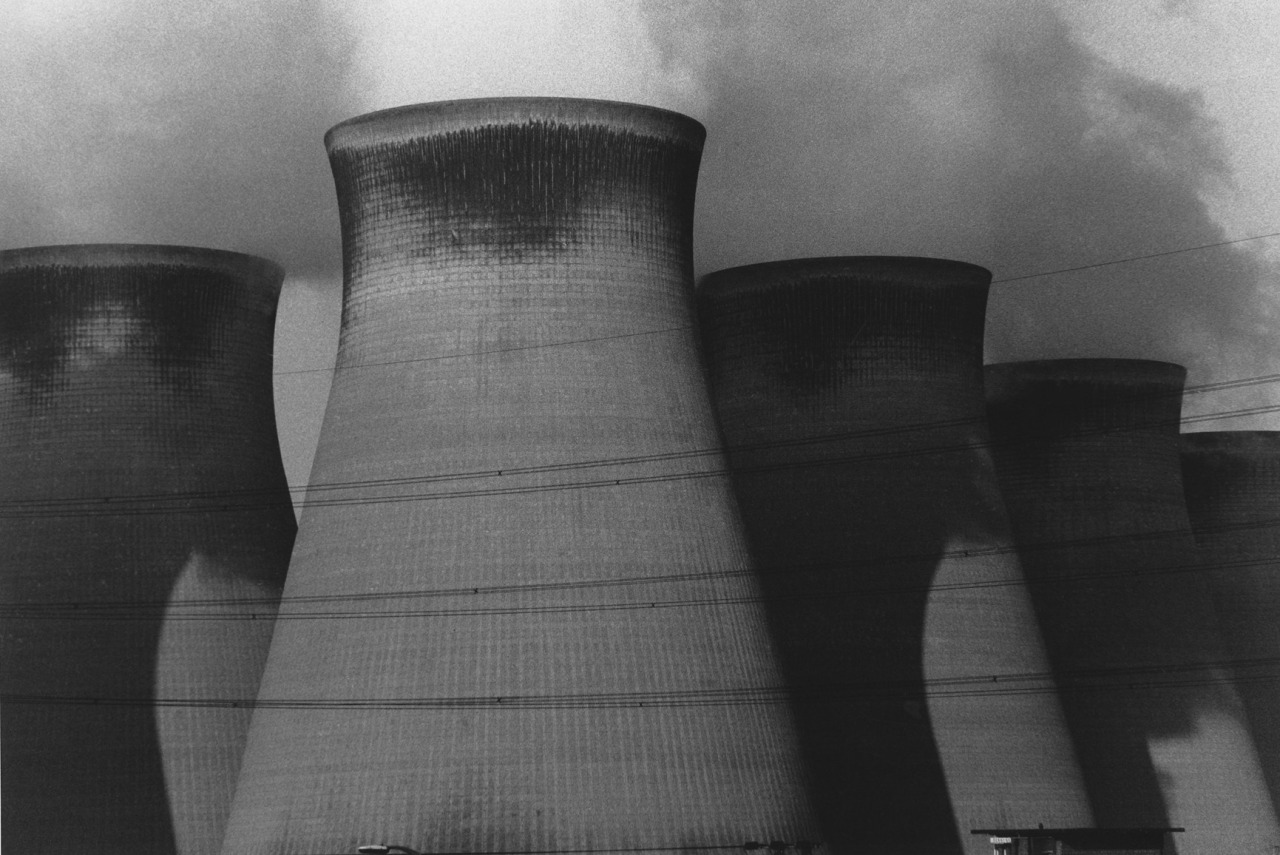

David Lynch’s break out movie, Eraserhead, is the sort of movie that will seep into your unconscious and stay with you for days or weeks – like a particularly unnerving nightmare. Shot in inky black and white, the film achieves its uncanny power in part because of its setting — a rotting industrial moonscape bereft of nature. Much of the film’s soundtrack is filled with the clanking of distant machines and the hissing of steam escaping pipes.

Lynch’s obsession with the remnants of the industrial revolution have punctuated much of his work since — from the grimy, claustrophobic Victorian streets in The Elephant Man to the opening titles of Twin Peaks to his 1990 avant-garde multimedia extravaganza Industrial Symphony No. 1.

“Well…if you said to me, ‘Okay, we’re either going down to Disneyland or we’re going to see this abandoned factory,’ there would be no choice,” said Lynch once in an interview. “I’d be down there at the factory. I don’t really know why. It just seems like such a great place to set a story.”

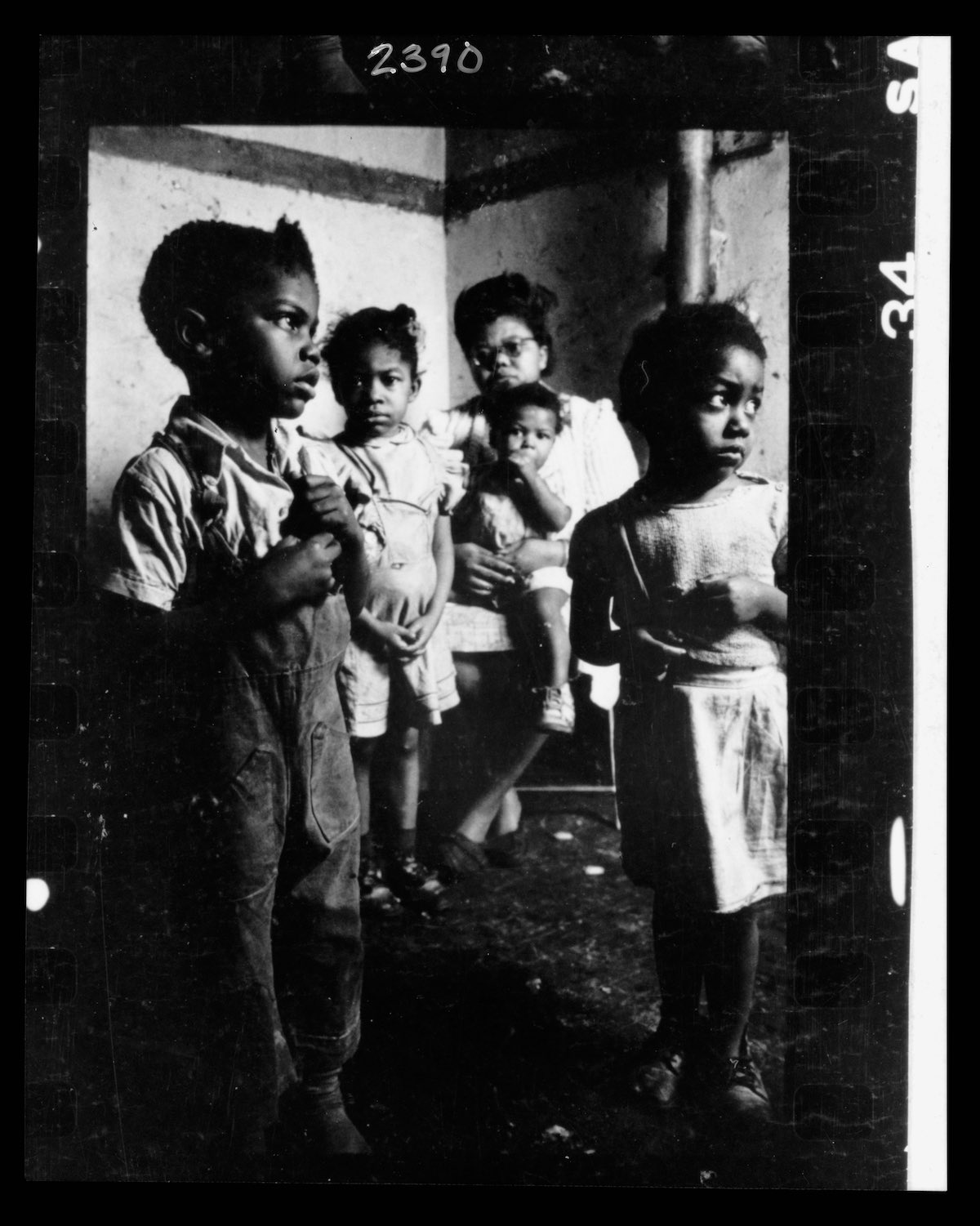

Earlier this year, Lynch exhibited at a London gallery a series of photographs he shot of, yes, rotting factories around New York, England and particularly Poland. The subjects of the photos are pretty mundane – a door, a window, a wall – but he imbues them with this odd tone of foreboding and menace. In other words, Lynch makes them seem Lynchian.

“It’s an incredible mood,” Lynch told Dazed Magazine. “I feel like I’m in a place that’s just magical, where nature is reclaiming these derelict factories. It’s very dreamy. Every place you turn, there’s something so sensational and surprising – it’s the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour. All the cities are looking more and more the same. The real treasures are going away; the mood they create is going away.”

See more photos below and, if you’re so inclined, you can buy the book to the exhibit here.

A window and a real estate opportunity in Lodz

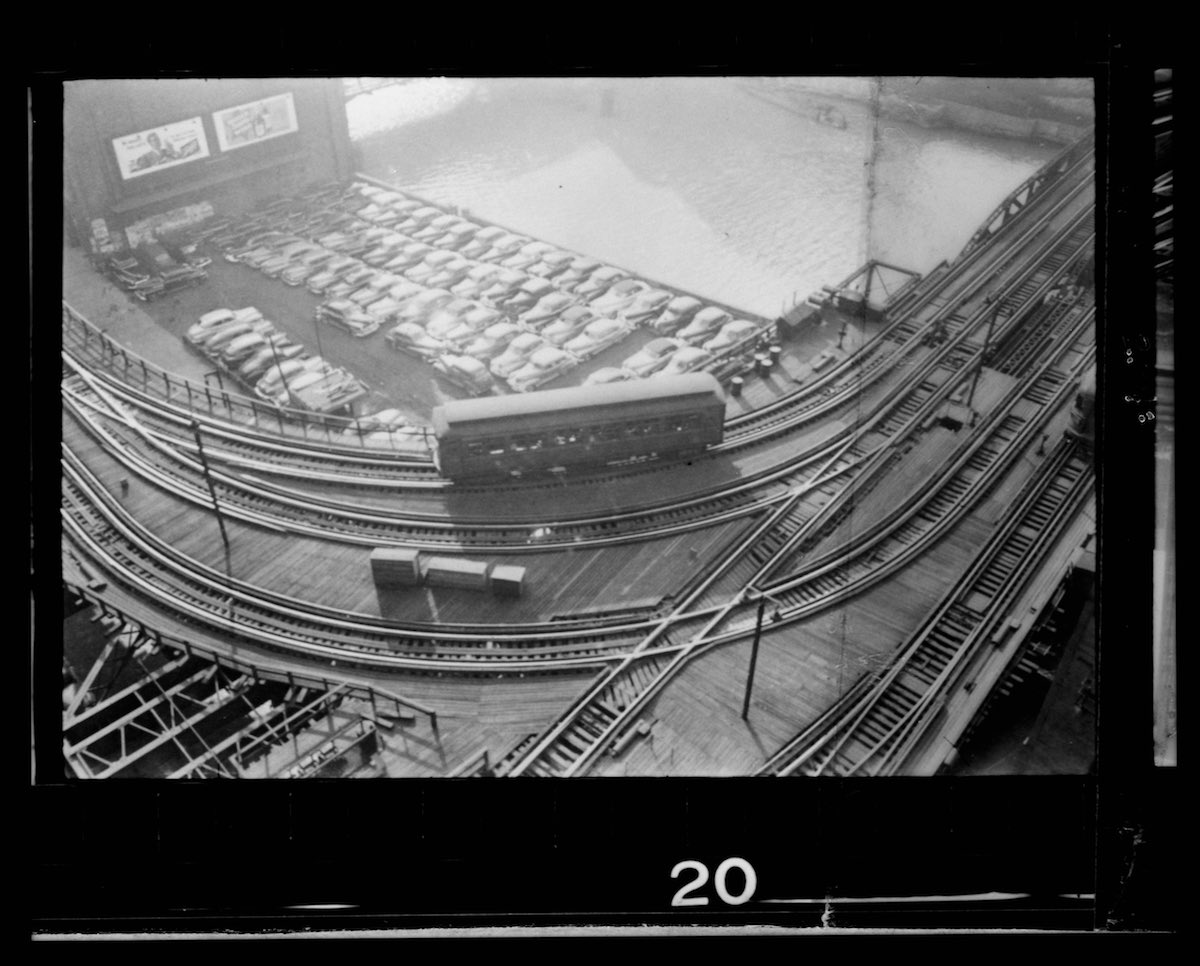

A factory. Lodz, Poland.

Related Content:

The Masterful Polaroid Pictures Taken by Filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

David Lynch Lists His Favorite Films & Directors, Including Fellini, Wilder, Tati & Hitchcock

Stanley Kubrick’s Jazz Photography and The Film He Almost Made About Jazz Under Nazi Rule

Young Stanley Kubrick’s Noirish Pictures of Chicago, 1949

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.