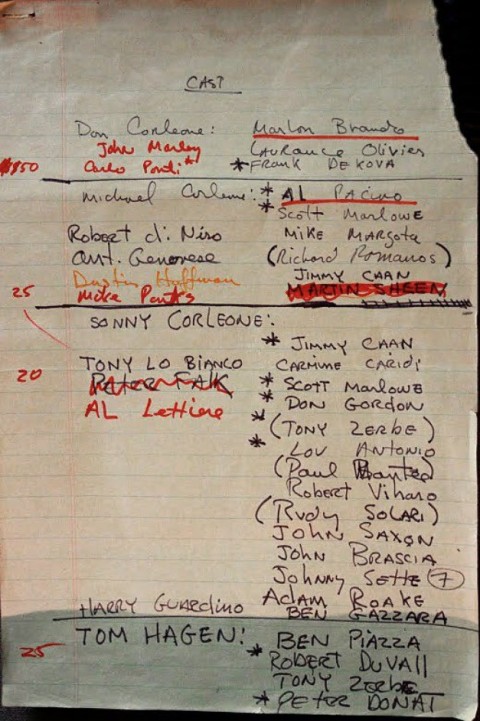

Laurence Olivier as Vito Corleone? Dustin Hoffman as Michael? Those are two of the intriguing options director Francis Ford Coppola was apparently mulling over when he jotted down these notes while preparing to make his classic 1972 film The Godfather.

The casting of The Godfather was a notoriously contentious affair. Executives at Paramount Pictures thought Marlon Brando — Coppola’s first choice to play Mafia “Godfather” Vito — was too difficult to work with. They thought Al Pacino was too short to play his son Michael.

“The war over casting the family Corleone was more volatile than the war the Corleone family fought on screen,” writes former Paramount head of production Robert Evans in his memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture. At one point the studio wanted Danny Thomas to play Vito and Warren Beatty to play Michael. A long list of leading Hollywood actors were considered for the role of Michael, including Robert Redford, Ryan O’Neal and Jack Nicholson.

Coppola eventually settled on Pacino as the cerebral Michael and the little-known Carmine Caridi as Michael’s tough-guy older brother, Sonny. Evans told the director he could have one but not both. In a passage from the book, quoted in Mark Seal’s 2009 Vanity Fair piece, “The Godfather Wars,” Evans describes a tense meeting with Coppola:

“You’ve got Pacino on one condition, Francis.”

“What’s that?”

“Jimmy Caan plays Sonny.”

“Carmine Caridi’s signed. He’s right for the role. Anyway, Caan’s a Jew. He’s not Italian.”

“Yeah, but he’s not six five, he’s five ten. This aint Mutt and Jeff. This kid Pacino’s five five, and that’s in heels.”

“I’m not using Caan.”

“I’m not using Pacino.”

Slam went the door. Ten minutes later, the door opened. “You win.”

For more on the casting of The Godfather, including excerpts from screen tests and remembrances from Coppola and others, see our earlier post “A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Casting of The Godfather with Coppola, De Niro & Caan.”

via A.V. Club