“Now when I was a little chap I had a passion for maps. I would look for hours at South America, or Africa, or Australia, and lose myself in the all the glories of exploration. At that time there were many blank spaces on the earth, and when I saw one that looked particularly inviting on a map (but they all look that) I would put my finger on it and say, ‘When I grow up I will go there.’”

—Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

In his post-WWII historical survey, The Story of Maps, Lloyd A. Brown observes that “the very material used in the making of maps, charts and globes contributed to their destruction.” Paper burns, rots, succumbs to water-damage and insects. Maps and globes made from solid silver, brass, copper, and other metals made too-tempting targets for looters and thieves. In this way, maps serve doubly as symbolic indices of what they represent—lands that, in the very act of mapping them, were often despoiled, overrun, and stolen from their inhabitants.

Moreover, in mapping history, it often happened that “if a map were old and obsolete and parchment was scarce, the old ink and rubrication could be scraped off and the skin used over again. This practice, accounting for the loss of many codices as well as valuable maps and charts, at one time became so pernicious” that the Catholic Church issued decrees to forbid it. What better allegory for conquest, the wiping away of civilizations in order to write new names and borders over them?

The old imperial tropes of “blank spaces” on the map and “dark places of the earth” (like “darkest Africa”), used with such effectiveness in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, hide the plain truth, in the words of Conrad’s Marlow:

The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea—something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to.…

Blank spaces represent those areas that had not yet been forcibly brought into the European economy of property, the sine qua non of Enlightenment humanity. “Once discovered by Europeans,” writes historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot—once classified, mapped, and made subject, “the Other finally enters the human world.” For several decades now, postcolonial projects have engaged in the progressive disenchantment of “the idea,” in the recognition of messy relationships between naming, mapping, and power, and the recovery, to the extent possible, of the names, borders, and identities beneath palimpsest histories.

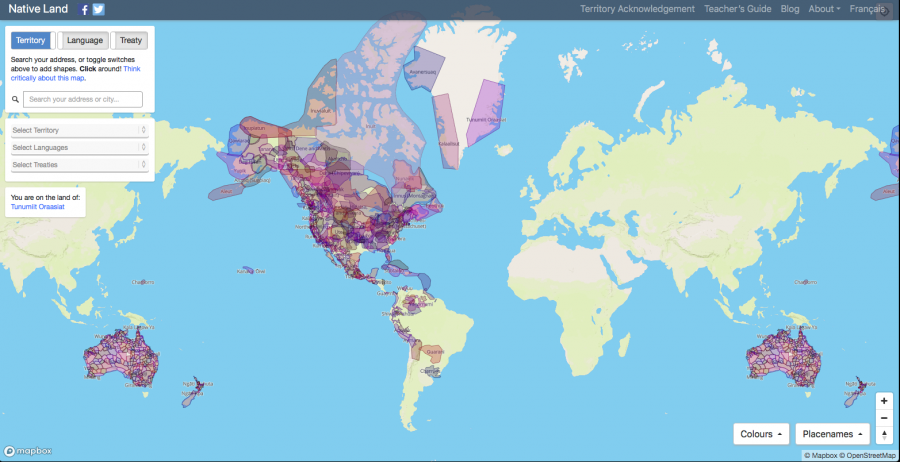

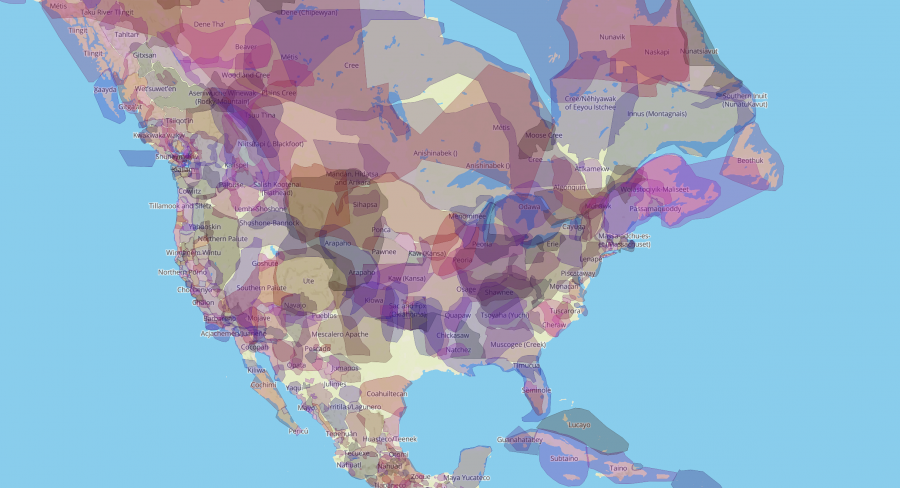

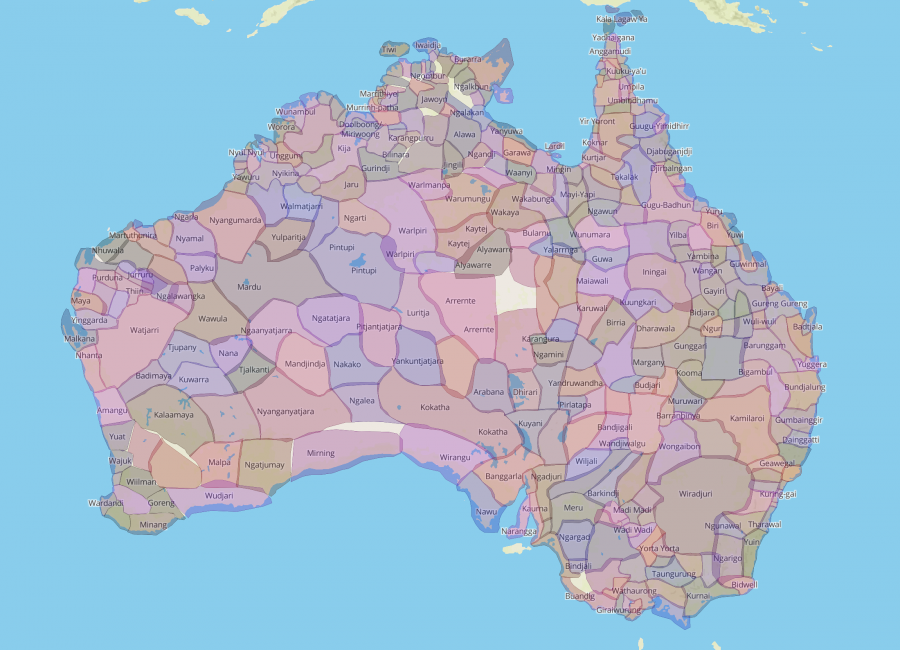

Such projects proliferate outside academia as technology amplifies previously unheard dissenting voices and perspectives and as, to use an old postcolonial phrase, “the empire writes back”—or, in this case, “maps back.” Such is the intent of the online project Native Land, an interactive website that “does the opposite” of centuries of colonial mapping, writes Atlas Obscura, “by stripping out country and state borders in order to highlight the complex patchwork of historic and present-day Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages that stretch across the United States, Canada,” the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, and Australia.

Also a mobile app for Apple and Android, the map allows visitors to enter street addresses or ZIP codes in the search bar, “to discover whose traditional territory their home was built on.”

White House officials will discover that 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is found on the overlapping traditional territories of the Pamunkey and Piscataway tribes. Tourists will learn that the Statue of Liberty was erected on Lenape land, and aspiring lawyers that Harvard was erected in a place first inhabited by the Wamponoag and Massachusett peoples.

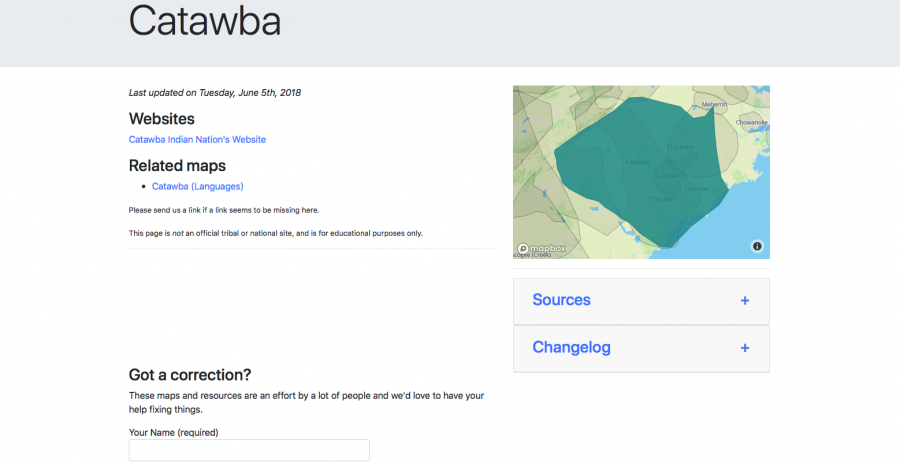

The map was created by Canadian activist and programmer Victor Temprano, founder of the company Mapster, which funds the project. Temprano prefaces the Native Land “About” page with a disclaimer: “This is not an academic or professional survey,” he writes, and is “constantly being refined from user input.” He defines his purpose as “helping people get interested and engaged” by asking questions like “who has the right to define where a particular territory ends, and another begins?”

As neo-colonial projects like oil pipelines once again threaten the survival of Indigenous communities, and indigenous people find themselves and their children caged in prisons for crossing militarized national borders, such questions could not be more relevant. Temprano does not make any claims to definitive historical accuracy and points to other, similar projects that supplement the “blank spaces” in his own online map, such as huge areas of South America being re-mapped on the ground by Amazonian tribes entering field data into smart phones, and Aaron Capella’s Tribal Nations Maps, which offers attractive printed products, perfect for use in classrooms.

Temprano quotes Capella in order to illuminate his work: “This map is in honor of all the Indigenous Nations [of colonial states]. It seeks to encourage people—Native and non-Native—to remember that these were once a vast land of autonomous Native peoples, who called the land by many different names according to their languages and geography. The hope is that it instills pride in the descendants of these People, brings an awareness of Indigenous history and remembers the Nations that fought and continue to fight valiantly to preserve their way of life.”

Visit Native Land here and enter an address in North or South America or Australia to learn about previous or concurrent Native inhabitants, their languages, and the historical treaties signed and broken over the centuries. Clicking on the territory of each Indigenous nation brings up links to other informative sites and allows users to submit corrections to help guide this inclusive project toward greater accuracy.

The site also features a Teacher’s Guide, Blog by Temprano, and a page on the importance of Territory Acknowledgement, a way for us to “insert an awareness of indigenous presence and land rights in everyday life,” and one of many “transformative acts,” as Chelsea Vowel, a Métis woman from the Plains Cree writes, “that to some extent undo Indigenous erasure.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness