Many of us now use the word hobo to refer to any homeless individual, but back in the America of the late 19th and early 20th century, to be a hobo meant something more. It meant, specifically, to count yourself as part of a robust culture of itinerant laborers who criss-crossed the country by hitching illegal rides on freight trains. Living such a lifestyle on the margins of society demanded the mastery of certain techniques as well as a body of secret knowledge, an aspect of the heyday of hobodom symbolized in the “hobo code,” a special hieroglyphic language explained in the Vox video above.

“Wandering from place to place and performing odd jobs in exchange for food and money, hobos were met with both open arms and firearms,” writes Antique Archaeology’s Sarah Buckholtz. “From illegally jumping trains to stealing scraps from a farmers market, the hobo community needed to create a secret language to warn and welcome fellow hobos that were either new to town or just passing through.”

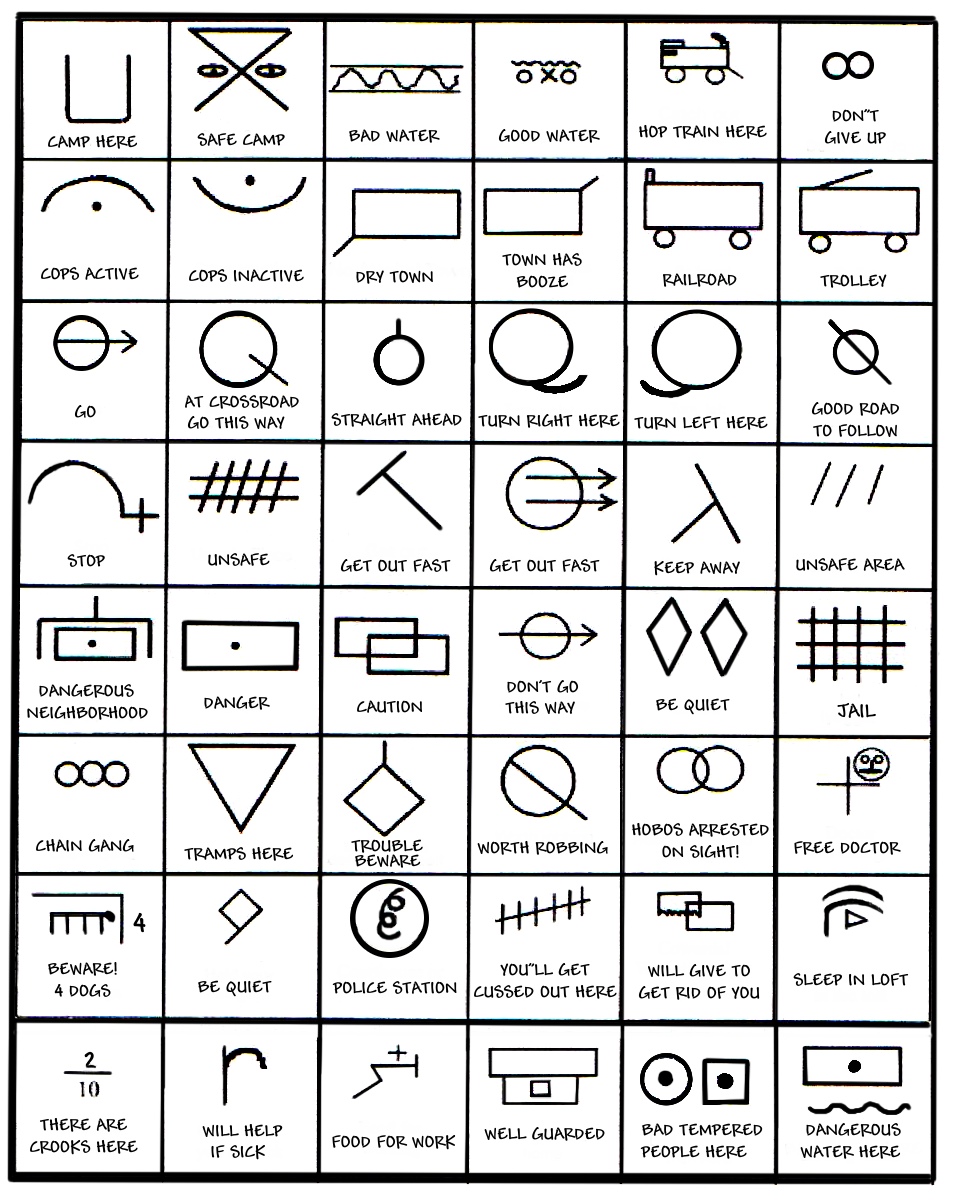

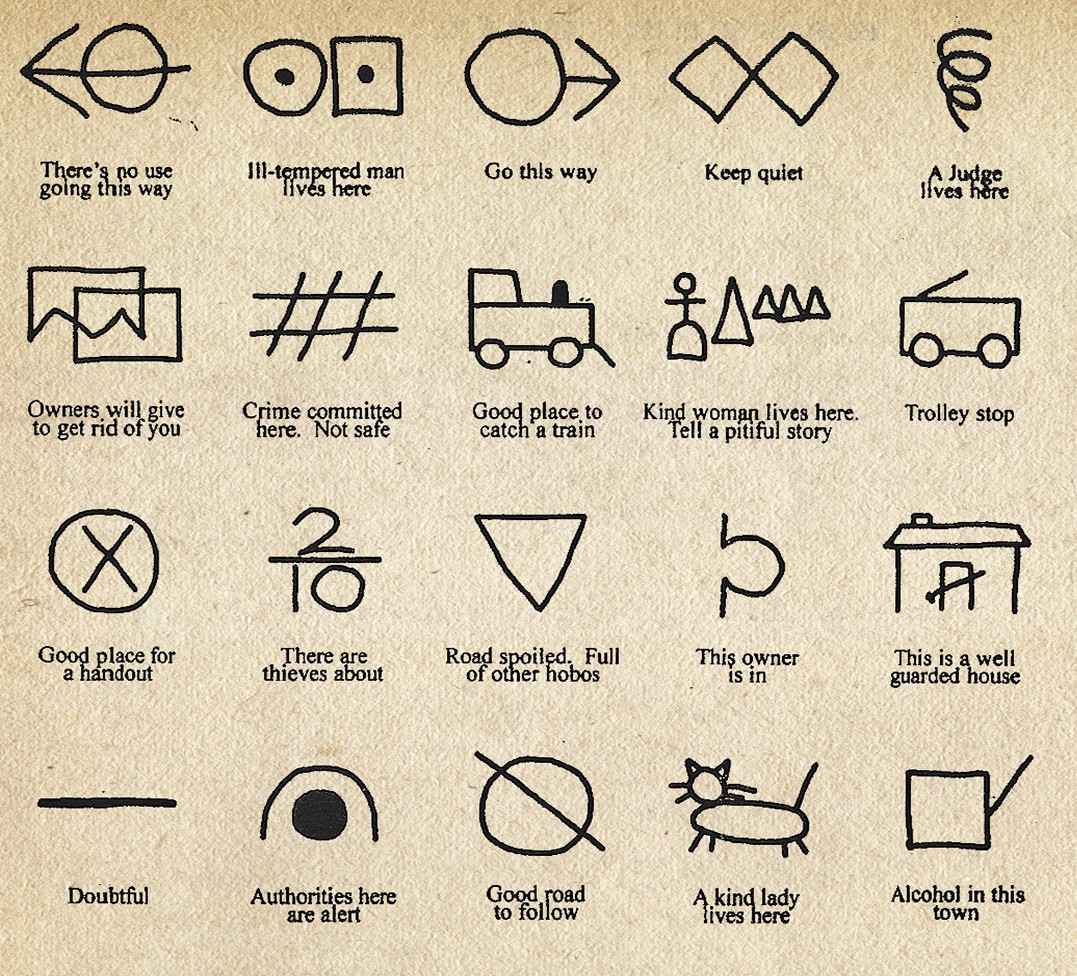

The code, written on brick walls, bases of water towers, or any other surface that didn’t move, “assigned circles and arrows for general directions like, where to find a meal or the best place to camp. Hashtags signaled danger ahead, like bad water or an inhospitable town.”

Hashtags sounds a bit Millennial for hobo culture, but on some level the term does make sense. Some of the abstracted symbols of the hobo code look a bit more like emoji: a locomotive meaning “good place to catch a train,” a building with a barred door meaning “this is a well-guarded house,” a cat meaning “a kind lady lives here.” But how much use did the hobo code actually see? “The problem is, all this information came from hobos, a group that took pride in their elusiveness and embellished storytelling,” says the Vox video’s narrator. “The truth is, there really isn’t any evidence that these signs were as widely used as the literature suggests.”

“Hobos used their mythology as a kind of cover,” says hobo historian Bill Daniel. “The tall tales, the drawings, even the books” — especially volumes penned by “A‑No.1,” the most famous hobo of them all — “were ways to project an image of themselves that both blew them up, but also kept them hidden.” Yet hobo ways, which encompassed even an ethical code that we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture, have their descendants. Take, for instance, the hobo practice of writing their nicknames, or “monikers,” on trains and elsewhere to show the world where they’d been and where they were headed. The line to modern urban graffiti almost draws itself, especially in the practice of subway-car “bombing” in 1970s and 80s New York. The hobo has gone, but the characteristically hardy hobo spirit finds a way to live on.

Related Content:

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Google Puts Online 10,000 Works of Street Art from Across the Globe

‘Boom Boom’ and ‘Hobo Blues’: Great Performances by John Lee Hooker

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.