It is my habit, when travel looms, to case the Internet for obscure museums my destination might have to offer. Once loaded, I fixate. Chat me up about my itinerary, and you will definitely come away with the impression that these offbeat locales are the trip’s primary raison d’être.

It’s shocking how rarely I actually make it to one of these off-the-beaten path gems. Time flies and I rarely travel alone these days.

Take a recent family trip to London. Every time I brought up the Museum of Brands, my husband expressed reservations. “But what is it, exactly, other than a bunch of old labels?” he’d press.

I hemmed and hawed, realizing on the cellular level that neither he nor the kids could see the beauty in old labels. Dinosaurs, maybe. Vespas, no doubt. But old labels? This is how I found myself giving the British Museum nearly three times the Museum of Brand’s admission charge to join a mighty throng of pensioners, squinting at a handful of boring button fragments and a chunk of wood that no longer resembled a Viking Ship.

Next time, I swear…

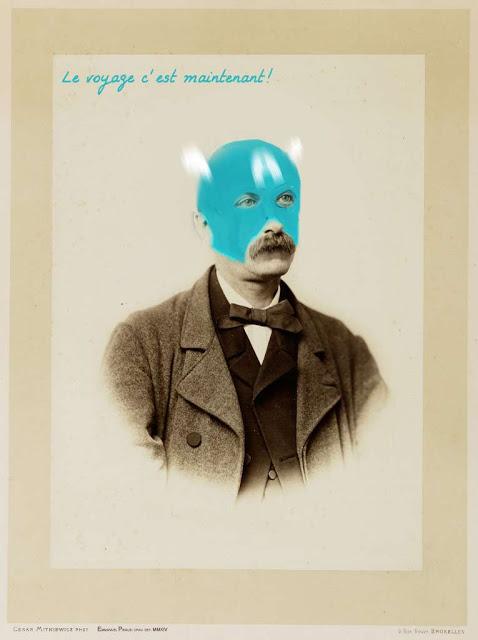

How fortunate for me and my ilk that Chicago design firm Coudal Partners is committed to laboring far outside its expected scope. In addition to championing Stanley Kubrick and poetry, they’ve taken it upon themselves to consolidate a panoply of digital collections into the Museum of Online Museums. (The preferred acronym is MoOM, FYI.)

Unlike that of certain of my traveling companions, Coudal Partners’ definition of what constitutes a museum is democratic. Generous, even. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Rijksmuseum, and the Musée d’Orsay share space with such non-brick-and-mortar companions as the Busy Beaver Button Museum, the Grocery List Collection, and Toaster Central.

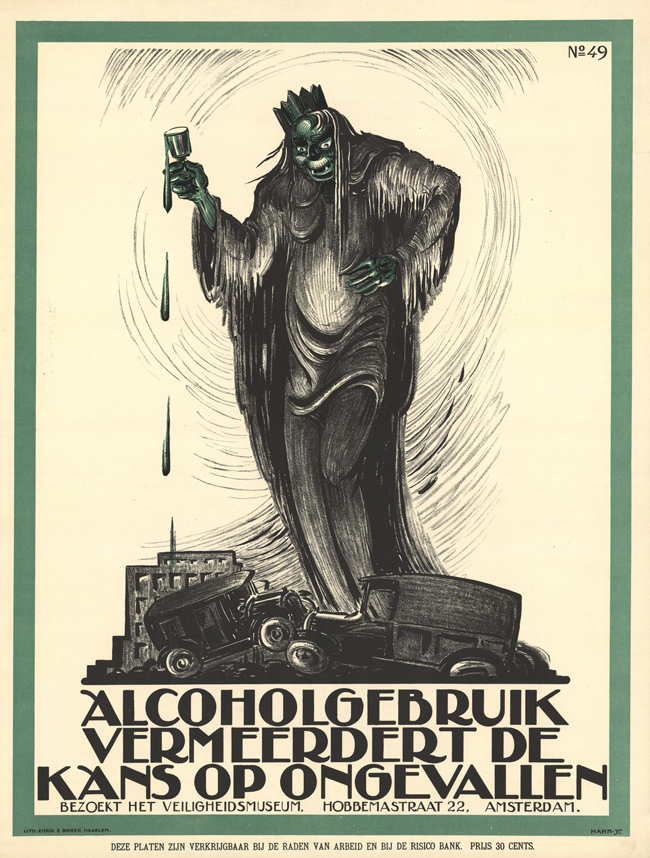

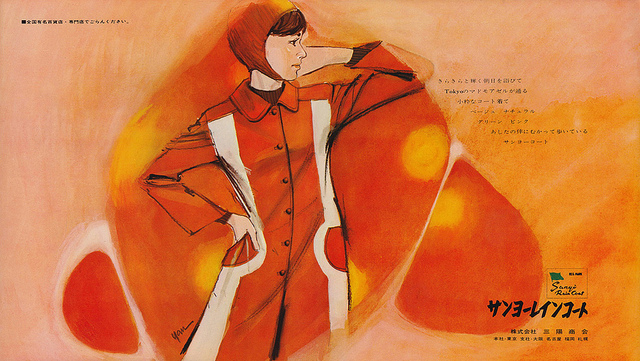

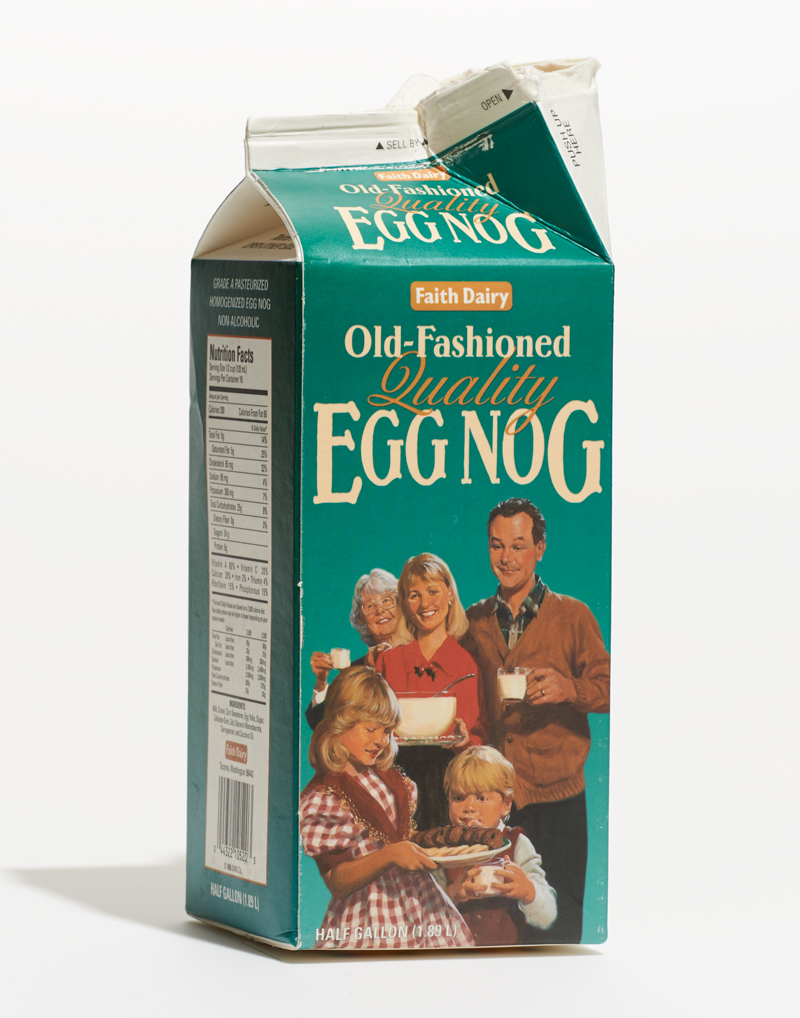

Like any major institution, MoOM touts their current exhibitions, a seasonal sampling of five. This spring brings together the Rijksmuseum’s Studio Project, NASA’s Space Food Hall of Fame, a collection of Dutch safety posters from 50 Watts, 40 retro-groovy Japanese ads compliments of Voices of East Anglia, and a photographic survey of eggnog cartons. (That last one really deserves a brick and mortar home. Location is immaterial. I’d just like to fantasize about visiting it someday.)

Meanwhile, the talk of the town here in New York City is the reappearance of Mmuseumm, an eclectic, non-profit housed in a 60-square-foot Tribeca elevator shaft. MoOM, take note.

Find more online exhibitions at the Museum of Online Museums.

Related Content:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

LA County Museum Makes 20,000 Artistic Images Available for Free Download

Download Over 250 Free Art Books From the Getty Museum

Ayun Halliday wrote about her experiences as a museum guard in her 3rd book, Job Hopper. Follow her @AyunHalliday