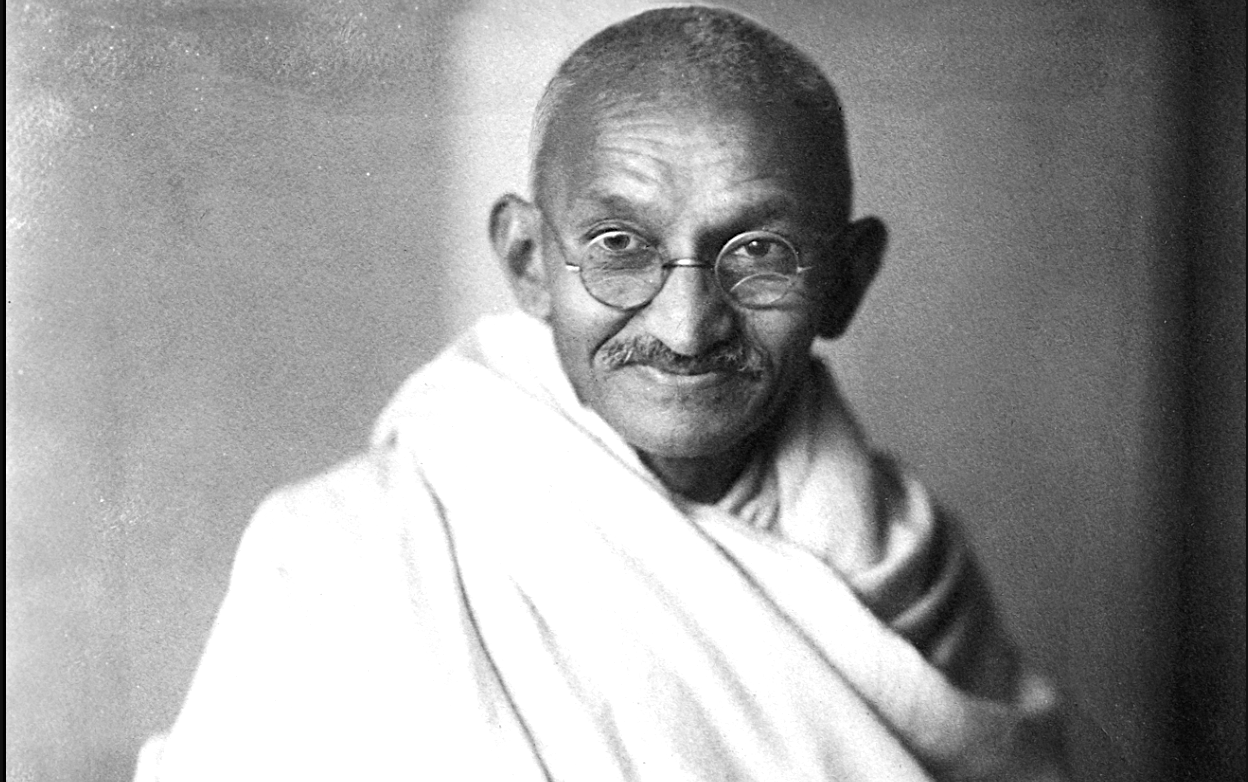

Neil deGrasse Tyson has spent his career talking up not just science itself, but also its practitioners. If asked to name the greatest scientist of all time, one might expect him to need a minute to think about it — or even to find himself unable to choose. But that’s hardly Tyson’s style, as evidenced by the clip above from his 92nd Street Y conversation with Fareed Zakaria. “Who do you think is the most extraordinary scientific mind that humanity has produced?” Zakaria asks. “There’s no contest,” Tyson immediately responds. “Isaac Newton.”

Those familiar with Tyson will know he would be prepared for the follow-up. By way of explanation, he narrates certain events of Newton’s life: “He, working alone, discovers the laws of motion. Then he discovers the law of gravity.” Faced with the question of why planets orbit in ellipses rather than perfect circles, he first invents integral and differential calculus in order to determine the answer. Then he discovers the laws of optics. “Then he turns 26.” At this point in the story, young listeners who aspire to scientific careers of their own will be nervously recalculating their own intellectual and professional trajectories.

They must remember that Newton was a man of his place and time, specifically the England of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. And even there, he was an outlier the likes of which history has hardly known, whose eccentric tendencies also inspired him to come up with powdered toad-vomit lozenges and predict the date of the apocalypse (not that he’s yet been proven wrong on that score). But in our time as in his, future (or current) scientists would do well to internalize Newton’s spirit of inquiry, which got him presciently wondering whether, for instance, “the stars of the night sky are just like our sun, but just much, much farther away.”

“Great scientists are not marked by their answers, but by how great their questions are.” To find such questions, one needs not just curiosity, but also humility before the expanse of one’s own ignorance. “I do not know what I may appear to the world,” Newton once wrote, “but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” Nearly three centuries after his death, that ocean remains forbiddingly but promisingly vast — at least to those who know how to look at it.

Related content:

Neil deGrasse Tyson on the Staggering Genius of Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton Conceived of His Most Groundbreaking Ideas During the Great Plague of 1665

Neil deGrasse Tyson Presents a Brief History of Everything in an 8.5 Minute Animation

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicted That the World Will End in 2060

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

Isaac Newton Creates a List of His 57 Sins (Circa 1662)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.