The French refer to the decade between 1920 and 1929 as les Années folles, “the crazy years,” which is apt when you consider how the French middle and upper classes generally loosened their brassieres and defined modern bohemia, à la Coco Chanel.

But the American moniker — the Roaring 20s — fits too. Nearly everything about that decade roared: cars, jazz, manufacturing, construction.

Din, in fact, came to define the age, particularly in big cities and especially in New York. An unnamed Japanese visitor was quoted upon his visit to that city in 1920: “My first impression of New York was its noise. When I know what they mean, I will understand civilization.”

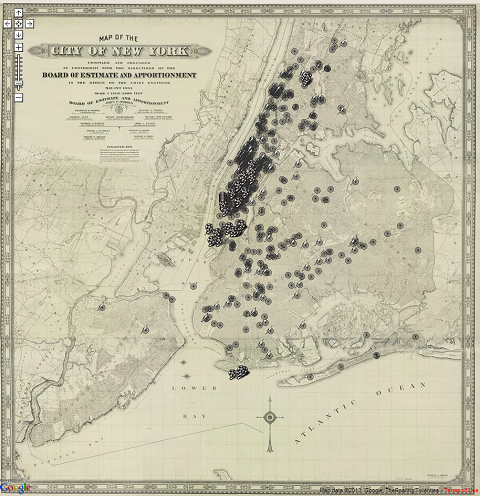

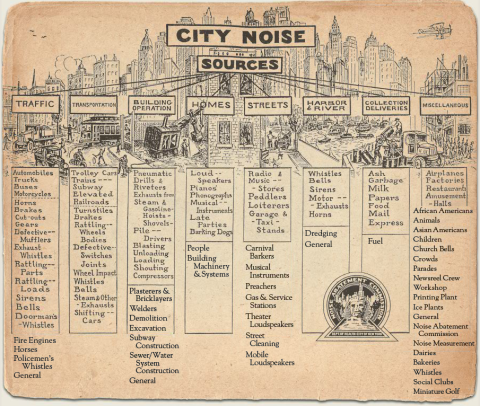

A Princeton history professor took that challenge at face value, while capturing a broader industrial era. The Roaring Twenties is an audio (and to some extent video) archive of what New York City sounded like from 1900 to 1933. Professor Emily Thompson and designer Scott Mahoy have created a lovely site that’s fun to explore. The archive includes a beautiful 1933 map of New York City loaded with links to noise complaints (screenshot at top), complete with documentation. New York had long been a place where people from all over the world lived on top of one another, but noise levels were shifting—getting louder and more varied, that is—and the city was inundated with complaints about ferry whistles, radio shops, street traffic, the clatter of restaurant dishwashing, and all manner of construction.

Sensitivity to the city’s volume was high. The city’s Noise Abatement Commission measured the “deafening effect” of sound in Times Square. The women’s cafeteria in the New York Life Insurance building was designed with state-of-the-art acoustics to keep the noise of the city out and the sound of office workers in.

Cortlandt Street in lower Manhattan was lined with radio shops, each broadcasting different music. Don’t miss that video, which you’ll find by scanning the Space tab map.

You can also move through time on the site, listening to the city’s cacophony from the early 1900s up to the 1930s, or browse a menu of noise sources from home sounds to the noise of the harbors and rivers. Again, you can visit the The Roaring Twenties site here.

via i09

Related Content:

Alan Lomax’s Music Archive Houses Over 17,400 Folk Recordings From 1946 to the 1990s

The Challenge of Archiving Sound + Vision in the 21st Century

Kate Rix writes about education and digital media. Follow her on Twitter.