You know the character Boo Radley? Well, if you know Boo, then you understand why I wouldn’t be doing an interview. Because I am really Boo.

– Harper Lee, in a private conversation with Oprah Winfrey

Author Harper Lee loved writing but resisted interviews, granting just a handful in the fifty-six years that followed the publication of her Pulitzer Prize winning 1960 novel, To Kill a Mockingbird.

Go Set a Watchman, her second, and final, novel began as an early draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, and was published in 2015, a year before her death.

Roy Newquist, interviewing Lee in 1964 for WQXR’s Counterpoint, above, probably expected the hotshot young novelist had many more books in her when he solicited her advice for “the talented youngster who wants to carve a career as a creative writer.”

Presumably Lee did too. “I hope to goodness that every novel I do gets better and better, not worse and worse,” she remarked toward the end of the interview.

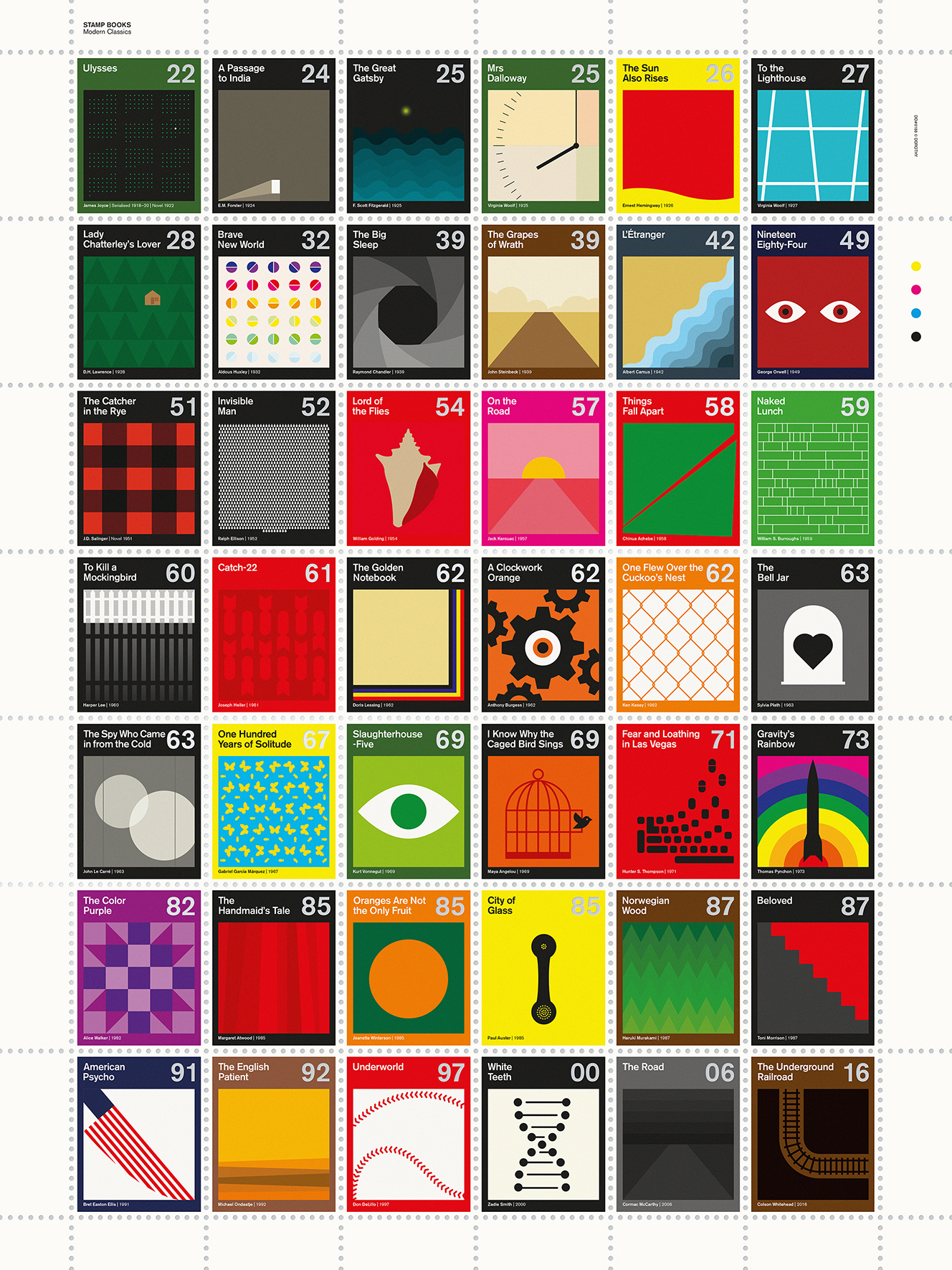

She obliged Newquist by offering some advice, but stopped short of offering career tips to those eager for the lowdown on how to write an instant bestseller that will be adapted for stage and screen, earn a perennial spot in middle school curriculums, and — just last week — be crowned the Best Book of the Past 125 Years in a New York Times readers’ poll, beating out titles by well regarded, and vastly more prolific authors on the order of J.R.R. Tolkien, George Orwell, Gabriel García Márquez, and Toni Morrison.

“People who write for reward by way of recognition or monetary gain don’t know what they’re doing. They’re in the category of those who write; they are not writers,” she drawled.

Harper Lee’s Advice to Young Writers

- Hope for the best and expect nothing in terms of recognition

- Write to please an audience of one: yourself

- Write to exorcise your divine discontent

- Gather material from the world around you, then turn inward and reflect

- Don’t major in writing

Listening to the recording, it occurs to us that this interview contains some more advice for young writers, or rather, those bringing up children in the digital age.

When Newquist wonders why it is that “such a disproportionate share of our sensitive and enduring fiction springs from writers born and reared in the South,” Lee, a native of Monroeville, Alabama, makes a strong case for cultivating an environment wherein children have no choice but to make their own fun:

I think … the absence of things to do and see and places to go means a great deal to our own private communication. We can’t go to see a play; we can’t go to see a big league baseball game when we want to. We entertain ourselves.

This was my childhood: If I went to a film once a month it was pretty good for me, and for all children like me. We had to use our own devices in our play, for our entertainment. We didn’t have much money. Nobody had any money. We didn’t have toys, nothing was done for us, so the result was that we lived in our imagination most of the time. We devised things; we were readers, and we would transfer everything we had seen on the printed page to the backyard in the form of high drama.

Did you never play Tarzan when you were a child? Did you never tramp through the jungle or refight the battle of Gettysburg in some form or fashion? We did. Did you never live in a tree house and find the whole world in the branches of a chinaberry tree? We did.

I think that kind of life naturally produces more writers than, say, an environment like 82nd Street in New York.

Hear that, parents and teachers of young writers?

- Nurture the creative spirit by regularly prying the digital device’s from young writers’ hands (and minds.)

Bite your tongue if, thus deprived, they trot off to the theater, the multiplex, or the sports stadium. Remember that iPhones hadn’t been invented when Lee was stumping for the tonic effects of her chinaberry tree. These days, any unplugged real world experience will be to the good.

If the young writers complain — and they surely will — subject yourself to the same terms.

Call it solidarity, self-care, or a way of upholding your New Year’s resolution…

Read an account of another Harper Lee interview, during her one day visit to Chicago to promote the 1962 film of To Kill a Mockingbird and attend a literary tea in her honor, here.

Related Content:

Harper Lee Gets a Request for a Photo; Offers Important Life Advice Instead (2006)

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.