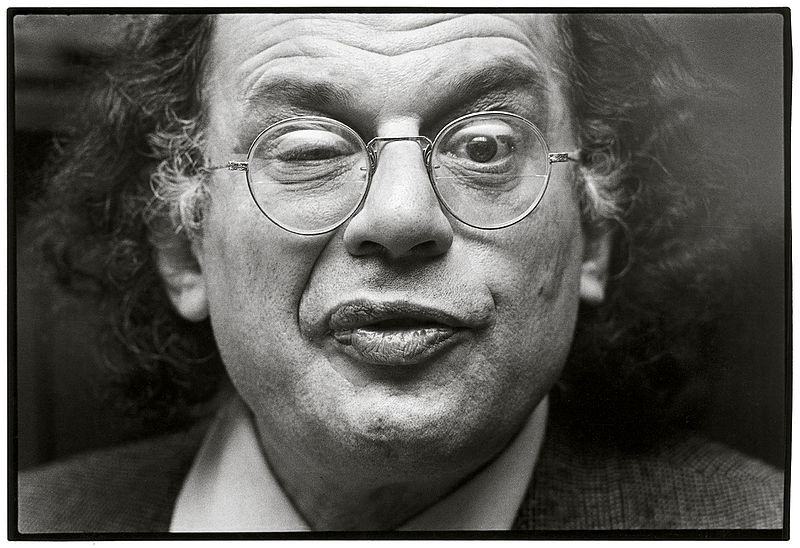

Image by Michiel Hendryckx, via Wikimedia Commons

Recent MacArthur Fellow and poet Terrence Hayes appeared on NPR yesterday to read and discuss his work; he was asked if he found “being defined as an African-American poet” to be limiting in some way. Hayes replied,

I think it’s a bonus. It’s a thing that makes me additionally interesting, is what I would say. So, black poet, Southern poet, male poet — many of those identities I try to fold into the poems and hope that they enrich them.

It seemed to me an odd question to ask a MacArthur-winning American poet. Issues of both personal and national identity have been central to American poetry at least since Walt Whitman or Langston Hughes, but especially since the 1950s with the emergence of confessional and beat poets like Allen Ginsberg. Without the celebration of personal identity, one might say that it’s hard to imagine American poetry.

Like Hayes, Ginsberg enfolded his various identities—Jew, Buddhist, gay man—into his poetry in enriching ways. Thirty-six years ago, he gave a radio interview to “Stonewall Nation,” one of a handful of specifically gay radio programs broadcast in 1970s Western New York. In an occasionally NSFW conversation, he discussed the experience of coming out to his fellow Beats and to his family.

- Introduction (5:21):

MP3

MP3 - On being closeted (2:09):

MP3

MP3 - Excerpts from “Don’t Grow Old” (2:32):

MP3

MP3 - On coming out to his family (3:01):

MP3

MP3 - On desire and compassion (1:41):

MP3

MP3 - On the Briggs amendment (8:54):

MP3

MP3 - On the Beats and nature (3:24):

MP3

MP3 - On Rocky Flats (2:19):

MP3

MP3 - Ginsberg sings “Everybody Sing” (2:37):

MP3

MP3

During the interview Ginsberg talks about being closeted and having a crush on Jack Kerouac, who was “very tolerant, friendly,” after Ginsberg confessed it. Above he tells a funny story about coming out to his father, then reads a moving untitled poem about his father’s eventual acceptance after their mutual “timidity and fear.” He also recalls how the rest of his family, particularly his brother, reacted.

The interview moves to broader topics. Ginsberg discusses his views on desire and compassion, defining the latter as “benevolent and indifferent attentiveness,” rather than “heart-love.” Buddhism pervades Ginsberg’s conversation as does a roguish vaudevillian sensibility mixed with sober reflection. He opens with a long, boozy sing-along whose first four lines concisely sum up core Buddhist doctrines; he ends with a funny, bawdy song that then becomes a dark exploration of homophobic and misogynistic violence.

Ginsberg and host also discuss the Briggs Initiative (above) a piece of legislation that would have been an effective purge in the California school system of gay teachers, their supporters, even those who might “take a neutral attitude which could be interpreted as approval.” This would preclude even the teaching of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (or one particular section of it), which, Ginsberg says, “would make the teacher liable for encouraging homosexual activity.” The amendment—one that, apparently, former governor Ronald Reagan strongly opposed—failed to pass. These days such proposals target Ginsberg’s poetry as well, and we still have conversations about the value of things like “benevolent and indifferent attentiveness” in the classroom, or whether poets should feel limited by being who they are.

In the photo above, taken by Herbert Rusche in 1978, you can see Ginsberg (left) with his long-time partner, the poet Peter Orlovsky (right).

via PennSound

Related Content:

The First Recording of Allen Ginsberg Reading “Howl” (1956)

“Expansive Poetics” by Allen Ginsberg: A Free Course from 1981

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

MP3

MP3