Perhaps the most famous of all literary recluses, despite herself, Emily Dickinson left a posthumously discovered cache of poetry that did not receive a proper scholarly treatment until the publication of The Poems of Emily Dickinson by Thomas H. Johnson in 1955, which made available Dickinson’s complete body of 1,775 poems in their intended state of punctuation and capitalization. For the first time, readers outside the small Dickinson family circle could read the work she circulated privately in so-called “fascicles” as well as the hundreds of poems no one had seen during her lifetime. There is some question over whether Dickinson wished to publish for a wider audience. She shared her work only with family and friends, some of whom published ten of her poems in newspapers between 1850 and 1866, most likely without her knowledge or consent. Many urged Dickinson to publish. Author Helen Hunt Jackson wrote to her: “You are a great poet—and it is a wrong to the day you live in, that you will not sing aloud.” Nevertheless, Dickinson “hesitated,” an important word in her lexicon, expressive of her profound agnostic doubts about the value of fame, success, and immortality.

Possibly due to the lack of scholarly interest before Johnson’s collection, Dickinson’s trove of manuscript drafts has remained scattered across several archives, sending researchers hoofing it to several institutions to view the poet’s handiwork. As of today, that will no longer be necessary with the inauguration of the online Emily Dickinson Archive, “an open-access website for the manuscripts of Emily Dickinson” that brings together thousands of manuscripts held by Harvard, Amherst, the Boston Public Library, the Library of Congress, and four other collections. Though nothing can substitute for the almost mystical feeling of being in the physical presence of a favorite author’s artifacts, the site is an enormous boon to scholars and lay readers alike, since it is open to anyone, unlike most special collections in university libraries (although browsing the thousands of handwritten images can be exhausting unless one knows what to look for).

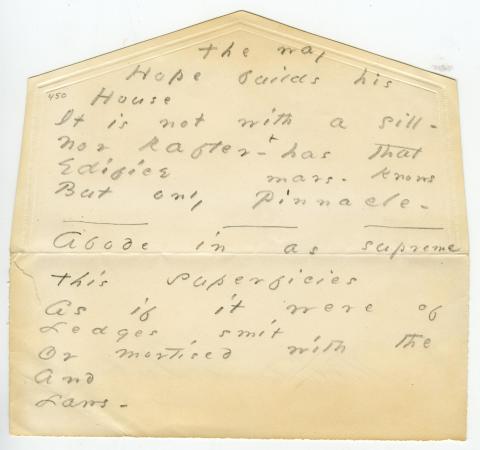

As The New York Times describes it, the archives’ creation led to some dissention among participating institutions. For the past year, Amherst has maintained an online database of their Dickinson collection (including the manuscript of “The way Hope builds his house,” above). Harvard has been more reluctant to make its manuscripts available. Nevertheless, the project’s general editor, Leslie M. Morris, says that the aim of the archive “was to downplay the issue of ownership and focus on Emily Dickinson and her manuscripts.” No behind the scenes wrangling seems to have interfered with the website’s ease of use. Readers can search the text of manuscript images or browse images by library collection, first line, date, recipient (of letters), or edition. The site also includes a “Lexicon,” with definitions of the poet’s favorite words from her own dictionary, Webster’s 1844 American Dictionary of the English Language, and users can also search for poems by word. All in all it’s an impressive project made all the more so by its free availability.

Related Content:

The Second Known Photo of Emily Dickinson Emerges.

Hear Walt Whitman (Maybe) Reading the First Four Lines of His Poem, “America” (1890)

Penn Sound: Fantastic Audio Archive of Modern & Contemporary Poets

The James Merrill Digital Archive Lets You Explore the Creative Life of a Great American Poet

Bill Murray Reads Poetry at a Construction Site

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness