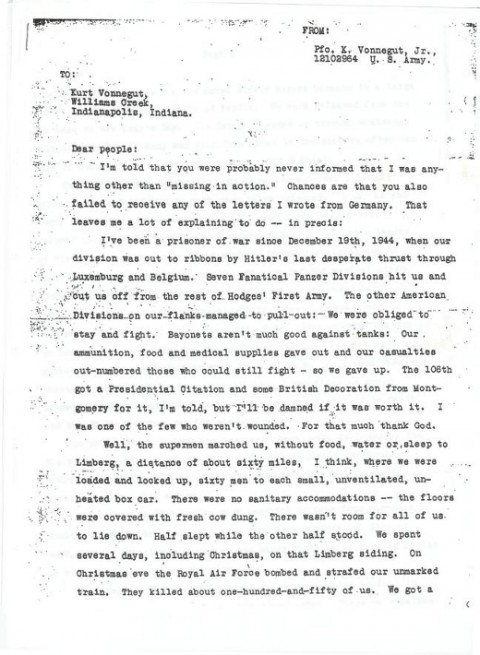

If you read Open Culture, smart money says you’ll also enjoy Letters of Note, a site we occasionally reference. They collect, post, and provide context for “fascinating letters, postcards, telegrams, faxes, and memos” to and from all manners of luminaries throughout the history of art, politics, music, science, media, and, er, letters. Dig into the archives and you’ll find a missive home from Kurt Vonnegut, a notable letter-writer if ever there was one. Dedicated Vonnegut readers will recognize the tone of the novelist, although here, at the age of 22, he had yet to become one. A Private in the Second World War, he was taken prisoner on December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge. Having then done time in an underground section of a Dresden work camp known, yes, as “Slaughterhouse Five,” he survived the subsequent bombing of the city and wound up in a repatriation camp by May 1945. There, he wrote what follows:

Dear people:

I’m told that you were probably never informed that I was anything other than “missing in action.” Chances are that you also failed to receive any of the letters I wrote from Germany. That leaves me a lot of explaining to do — in precis:

I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944, when our division was cut to ribbons by Hitler’s last desperate thrust through Luxemburg and Belgium. Seven Fanatical Panzer Divisions hit us and cut us off from the rest of Hodges’ First Army. The other American Divisions on our flanks managed to pull out: We were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren’t much good against tanks: Our ammunition, food and medical supplies gave out and our casualties out-numbered those who could still fight — so we gave up. The 106th got a Presidential Citation and some British Decoration from Montgomery for it, I’m told, but I’ll be damned if it was worth it. I was one of the few who weren’t wounded. For that much thank God.

Well, the supermen marched us, without food, water or sleep to Limberg, a distance of about sixty miles, I think, where we were loaded and locked up, sixty men to each small, unventilated, unheated box car. There were no sanitary accommodations — the floors were covered with fresh cow dung. There wasn’t room for all of us to lie down. Half slept while the other half stood. We spent several days, including Christmas, on that Limberg siding. On Christmas eve the Royal Air Force bombed and strafed our unmarked train. They killed about one-hundred-and-fifty of us. We got a little water Christmas Day and moved slowly across Germany to a large P.O.W. Camp in Muhlburg, South of Berlin. We were released from the box cars on New Year’s Day. The Germans herded us through scalding delousing showers. Many men died from shock in the showers after ten days of starvation, thirst and exposure. But I didn’t.

Under the Geneva Convention, Officers and Non-commissioned Officers are not obliged to work when taken prisoner. I am, as you know, a Private. One-hundred-and-fifty such minor beings were shipped to a Dresden work camp on January 10th. I was their leader by virtue of the little German I spoke. It was our misfortune to have sadistic and fanatical guards. We were refused medical attention and clothing: We were given long hours at extremely hard labor. Our food ration was two-hundred-and-fifty grams of black bread and one pint of unseasoned potato soup each day. After desperately trying to improve our situation for two months and having been met with bland smiles I told the guards just what I was going to do to them when the Russians came. They beat me up a little. I was fired as group leader. Beatings were very small time: — one boy starved to death and the SS Troops shot two for stealing food.

On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. their combined labors killed 250,000 people in twenty-four hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.

After that we were put to work carrying corpses from Air-Raid shelters; women, children, old men; dead from concussion, fire or suffocation. Civilians cursed us and threw rocks as we carried bodies to huge funeral pyres in the city.

When General Patton took Leipzig we were evacuated on foot to (‘the Saxony-Czechoslovakian border’?). There we remained until the war ended. Our guards deserted us. On that happy day the Russians were intent on mopping up isolated outlaw resistance in our sector. Their planes (P‑39’s) strafed and bombed us, killing fourteen, but not me.

Eight of us stole a team and wagon. We traveled and looted our way through Sudetenland and Saxony for eight days, living like kings. The Russians are crazy about Americans. The Russians picked us up in Dresden. We rode from there to the American lines at Halle in Lend-Lease Ford trucks. We’ve since been flown to Le Havre.

I’m writing from a Red Cross Club in the Le Havre P.O.W. Repatriation Camp. I’m being wonderfully well feed and entertained. The state-bound ships are jammed, naturally, so I’ll have to be patient. I hope to be home in a month. Once home I’ll be given twenty-one days recuperation at Atterbury, about $600 back pay and — get this — sixty (60) days furlough.

I’ve too damned much to say, the rest will have to wait, I can’t receive mail here so don’t write.

May 29, 1945

Love,

Kurt — Jr.

Related content:

Kurt Vonnegut Reads from Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut’s Eight Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story

Kurt Vonnegut: “How To Get A Job Like Mine” (2002)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.