When you think of the accomplishments of the Islamic world, what comes to mind? For most of this century so far, at least in the West, the very notion has had associations in many minds with not creation but destruction. In 2002, mathematician Keith Devlin lamented how “the word Islam conjures up images of fanatical terrorists flying jet airplanes full of people into buildings full of even more people” and “the word Baghdad brings to mind the unscrupulous and decidedly evil dictator Saddam Hussein.” Ironically, writes Devlin, “the culture that these fanatics claim to represent when they set about trying to destroy the modern world of science and technology was in fact the cradle in which that tradition was nurtured. As mathematicians, we are all children of Islam.”

You don’t have to dig deep into history to discover the connection between Islam and mathematics; you can simply see it. “In Islamic culture, geometry is everywhere,” says the narrator of the brief TED-Ed lesson above. “You can find it in mosques, madrasas, palaces, and private homes.”

Scripted by writer and consultant on Islamic design Eric Broug, the video breaks down the complex, abstract geometric patterns found everywhere in Islamic art and design, from its “intricate floral motifs adorning carpets and textiles to patterns of tilework that seem to repeat infinitely, inspiring wonder and contemplation of eternal order.”

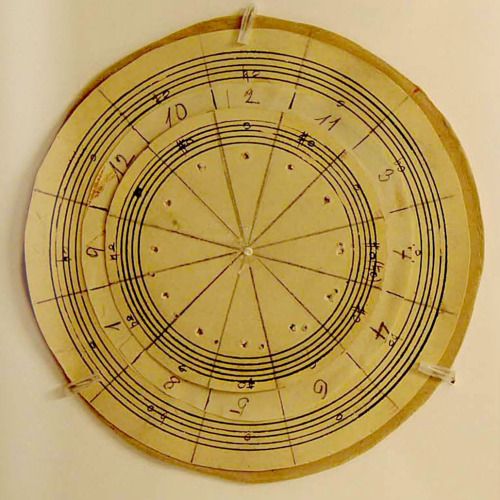

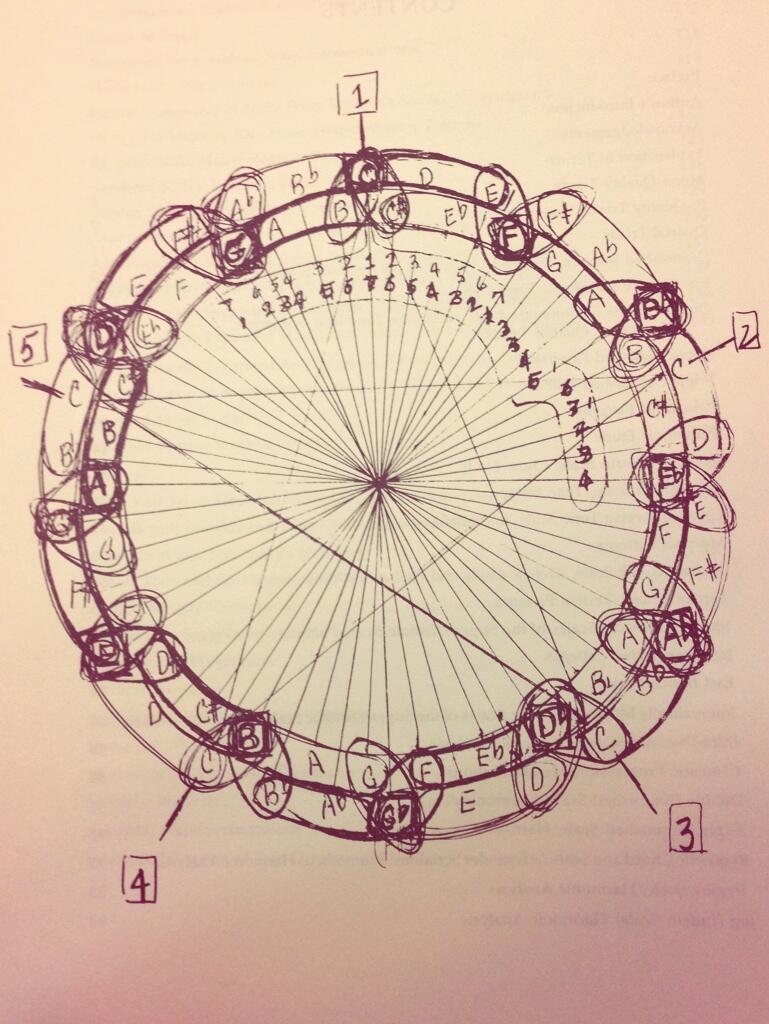

And the tools used to render these visions of eternity? Nothing more advanced than a compass and a ruler, Broug explains, used to first draw a circle, divide that circle up, draw lines to construct repeating shapes like petals or stars, and keep intact the grid underlying the whole pattern. The process of repeating a geometric pattern on a grid, called tessellation, may seen familiar indeed to fans of the mathematically minded artist M.C. Escher, who used the very same process to demonstrate what wondrous artistic results can emerge from the use of simple basic patterns. In fact, Escher’s Dutch countryman Broug once wrote an essay on the connections between his art and that of the Islamic world for the exhibit Escher Meets Islamic Art at Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum.

Escher first encountered tessellations on a trip to the Islamic world himself, in the “colorful abstract decorations in the 14th century Alhambra, the well-known palace and fortress complex in Southern Spain,” writes Al.Arte’s Aya Johanna Daniëlle Dürst Britt. “Although he visited the Alhambra in 1922 after his graduation as a graphic artist, he was already interested in geometry, symmetry and tessellations for some years.” His fascinations included “the effect of color on the visual perspective, causing some motifs to seem infinite — an effect partly caused by symmetry.” His second visit to Alhambra, in 1936, solidified his understanding of the principles of tessellation, and he would go on to base about a hundred of his own pieces on the patterns he saw there. Those who seek the door to infinity understand that any tradition may hold the keys.

Related Content:

How Arabic Translators Helped Preserve Greek Philosophy … and the Classical Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.