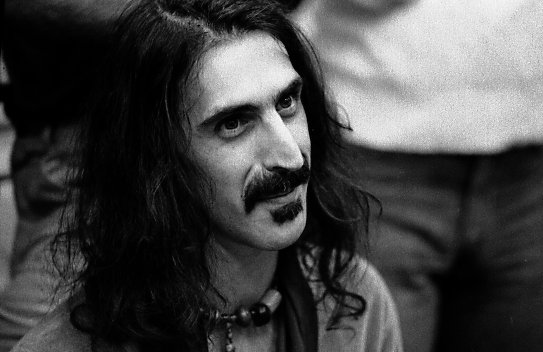

Popular music has a rich tradition of literary songwriters, including—to name but a few—Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Kate Bush, and even Alan Parsons, who released not one, but two concept albums based on the work of Edgar Allan Poe. And then there’s the inimitable Tom Waits, who doesn’t just work in a literary vein, but is a succession of pulpy characters, each one with the ability to light up a stage. Waits proved as much in 1988 when he toured his album Big Time, as alter-ego Frank O’Brien, a character he described as “a combination of Will Rogers and Mark Twain, playing accordion—but without the wisdom they possessed.” The Big Time tour, writes Dangerous Minds, was “like entering a sideshow tent in Tom Wait’s brain.”

In a review of the concert film of the same name, also released that year, the New York Times described Waits as a “gang of overlapping personas, a bunch of derelict philosopher-kings who rasp out romantic metaphors between wisecracks,” inhabiting “a seedy urban world of pawnshops and tattoos, of cigarette butts and polyester and triple‑X movies.” It’s hard to know, listening to Waits in the interview above from the year of Big Time the album, tour, and film, how many of his personae emerge from the woodshed and how many spring from grizzled voices in that sideshow brain, which must sound like a cacophony of old-time waltzes and scurrilous ragtimes; boozy big-band numbers carousing in louche cabarets; pianos drunkenly falling down stairs. Waits can tell stories beautiful and terrible, in talking blues, broken ballads, and sprechgesang, rivaling the best compositions of the Delta, the beats, and sailors and hoboes.

Or he can tell stories—as he does above—about moles, building under Stonehenge “the most elaborate system of mole catacombs,” being rewarded for “having the courage to tunnel under great rivers,” staging executions. Then he shifts the scene to New York, and a Mercedes pulls up in a puddle of blood. “I think you just write,” says Waits, “and you don’t try to make sense of it. You just put it down the way you got it.” Waits gets it in vivid, surrealist images, one bizarre and sordid detail after another. To hear him speak is to hear him compose. You can read the transcript of the short interview, recorded in London by Chris Roberts, but the effect of Waits-the-performer is entirely lost. Better to hear his cracked inflection, his driest of comic timing, and watch the excellent animation of PBS’s Blank on Blank team, who have previously brought us amusing cartoon accompaniments for interviews with B.B. King, Ray Charles, the Beastie Boys, and even Fidel Castro. Tom Waits, I think, has given them their best material yet.

Related Content:

Tom Waits, Playing the Down-and-Out Barfly, Appears in Classic 1978 TV Performance

Tom Waits Reads Two Charles Bukowski Poems, “The Laughing Heart” and “Nirvana”

Watch Tom Waits’ Classic Appearance on Australian TV, 1979

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness