People can, and do, spend lifetimes tracking down and cataloguing all of the various releases of their favorite bands—studio, stage, bootleg, and otherwise. Certain groups—the Grateful Dead, naturally (hear 9,000 Dead shows here)—encourage this more than others. And if a rock band can send completists on lifelong scavenger hunts, how much more so a prolific jazz artist such as, say, Miles Davis? Like the musical form itself, jazz artists are mercurial by nature, spending years as journeymen for any number of other bandleaders before breaking off to form their own quartets, quintets, sextets, etc. Add to the profusion of different groups the tendency of jazz players to record the same songs—but never in the same way—dozens, hundreds, of times, and you’ve got discographies that number well into double-digit page lengths.

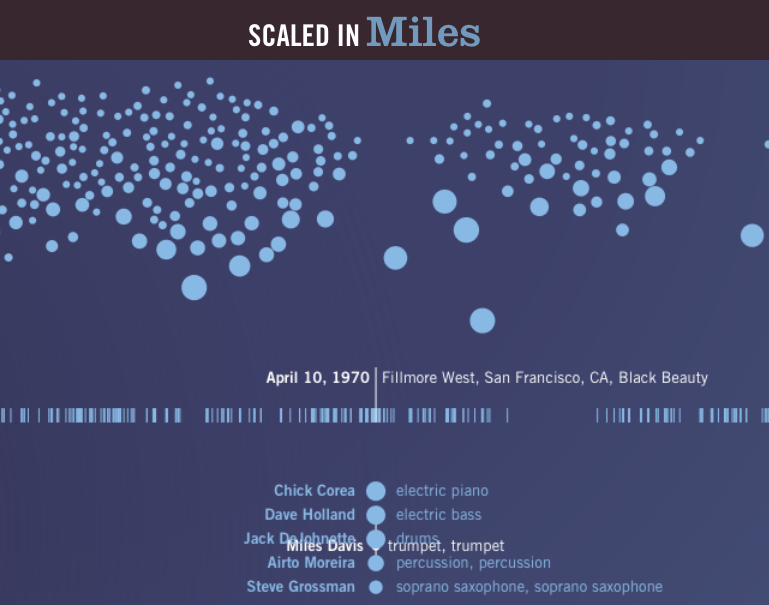

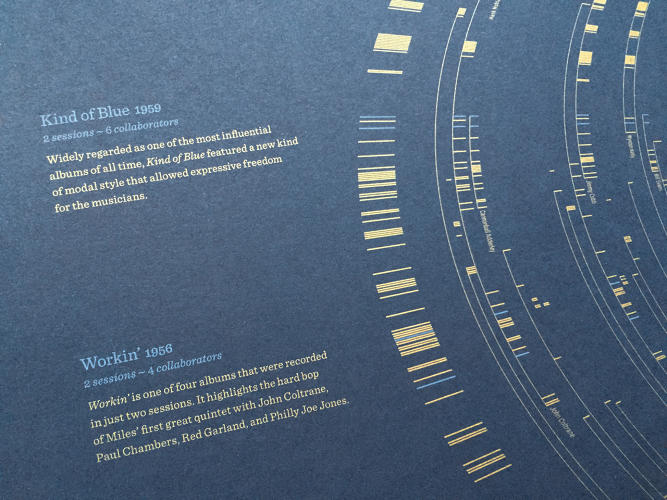

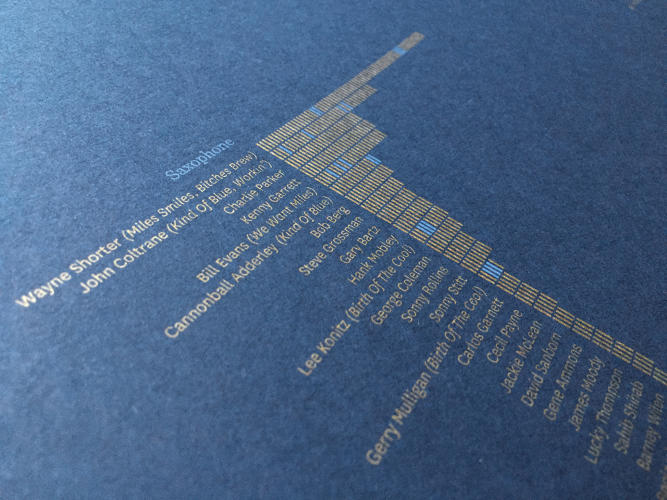

That’s the situation with Miles, for sure—even the most studied of his collectors couldn’t possibly call to mind all of his immense catalog without some handy reference guide. Perhaps “Scaled in Miles” can help. Condensing an incredible amount of musical history into a very concise and attractive form, “Scaled in Miles,” as it’s called—a huge online interactive discography—“tries to make sense of Davis’s storied career by visualizing each of the 577 artists he collaborated with over 405 recording sessions.” That description comes from Fast Company, who feature a few close-ups of the related “Scaled in Miles” poster, which they describe as resembling NASA’s “Golden Record.” The interactive visualization allows you to listen to the tunes as you learn the musicians who created them and the wheres and whens of their recordings.

Something about Miles’ music lends itself particularly well, I have to say, to the very streamlined, clean design of this impressive catalog’s online interface. Were someone enterprising enough to make one for the Grateful Dead, I’m guessing it would look less like a golden record in space and more like another, messier kind of spaced-out voyage. That’s not to suggest that Davis and the Dead have little in common but their vast recorded output. They did, after all, once share a stage at the Fillmore West in 1970. No need to go digging in the vaults to find that one; see the personnel from that night at the top of the post and stream the whole thing right here.

via Moses Hawk

Related Content:

The Miles Davis Story, the Definitive Film Biography of a Jazz Legend

The Night When Miles Davis Opened for the Grateful Dead in 1970: Hear the Complete Recordings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness