I discovered one of my favorite pieces of rock ‘n’ roll memorabilia—a full page ad for the 1983 album from David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust concert film—at a flea market. It’s a nice little piece of history, but a little bit misleading to consumers at the time, since it says, “featuring the single ‘White Light/White Heat.’” As everyone knows, “White Light/White Heat” is not a Bowie single, but a Lou Reed song, one of his many odes to heroin as lead singer of the Velvet Underground.

But whatever the admen had in mind in promoting this track over Bowie’s many original hits, the star himself has never been shy about acknowledging his debts. When it comes to Ziggy, “the songwriter who most influenced” the glam rock alien is certainly Reed, as Bowie himself says in this 1977 interview.

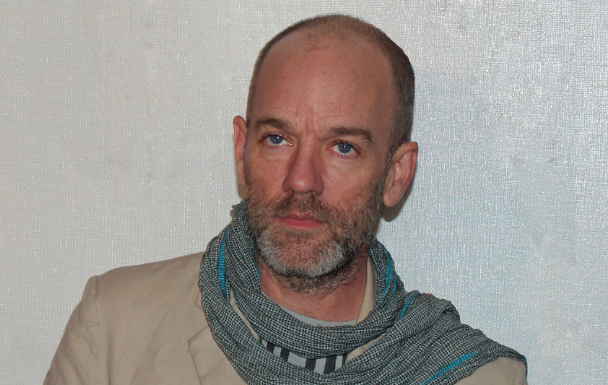

Today, on the one-year anniversary of Reed’s death, we revisit their creative and personal relationship, a mutual admiration that spanned more than four decades. Not only did Bowie cover Reed’s songs and produce his 1972 solo album Transformer, but he wrote 1971’s “Queen Bitch” as a tribute to Reed and the Velvets. In 1997, Bowie and Reed took the stage together to perform the song. The occasion was Bowie’s 50th birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden, and the all-star lineup that night included Frank Black, Dave Grohl, Sonic Youth, Robert Smith, and Billy Corgan (see the full setlist here). But Reed’s appearance was the most exciting, and in hindsight, most poignant. At the top of the post, see the two old friends play “Queen Bitch,” just above, they do “White Light/White Heat,” and below, Reed’s classic “Waiting for the Man” (they also played Reed’s 1989 “Dirty Boulevard” together).

At the time, Bowie was at “somewhat of a low point” in his career, writes Rolling Stone, though poised for a comeback with the upcoming single (and Trent Reznor-starring video) “I’m Afraid of Americans,” which he played with Sonic Youth that night. But the first time he and Reed shared the stage, in 1972, Bowie was riding high in all his Ziggy Stardust glory and regularly covering Velvet Underground songs on tour. That year, he brought Reed on stage in London for his “very, very first appearance on any stage in England.” Hear them do “White Light/White Heat” in somewhat muffled live audio below. They also played “Waiting for the Man” and “Sweet Jane” together, which you can hear at the bottom of the post.

While Bowie seems to have taken every opportunity to lavish praise on his idol, Reed was a bit more understated, though no less sincere, in his appreciation. In 2004, he told Rolling Stone, “We’re still friends after all these years. We go to the occasional art show and museum together, and I always like working with him […] I saw him play here in New York on his last tour, and it was one of the greatest rock shows I’ve ever seen. At least as far as white people go. Seriously.” Seriously, Lou Reed, you are sorely missed.

Related Content:

Rock and Roll Heart, 1998 Documentary Retraces the Remarkable Career of Lou Reed

Teenage Lou Reed Sings Doo-Wop Music (1958–1962)

David Bowie Recalls the Strange Experience of Inventing the Character Ziggy Stardust (1977)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness