The word “Wagnerian” as a synonym for operatic bombast may have fallen out of favor in recent years, as has the reputation of German composer Richard Wagner. He has been regarded as “the most repugnant of musical nationalists,” writes David P. Goldman at Tablet—a sentiment widely shared given Wagner’s permanent association with Nazism. His music has long been banned in Israel, though “every so often a prominent musician makes a point of sneaking Wagner into a public concert.” And just as philosophy departments across the world have struggled with Martin Heidegger’s Nazism, so the classical music and opera worlds have wrestled with Wagner.

What’s odd, however, in this case, is that Wagner died in 1883. He towered over 19th-century German culture, a contemporary of Nietzsche rather than Hitler, who claimed him after the composer’s death.

Yet those who know the story of Wagner’s turbulent friendship with Nietzsche know that the philosopher violently rejected his former idol and father figure in part because, as Robert Holub argues, Nietzsche “was unequivocally antagonistic toward what he understood as anti-Semitism and anti-Semites.” Nietzsche saw the writing on the wall in views Wagner expressed in essays like 1850’s “Judaism in Music.”

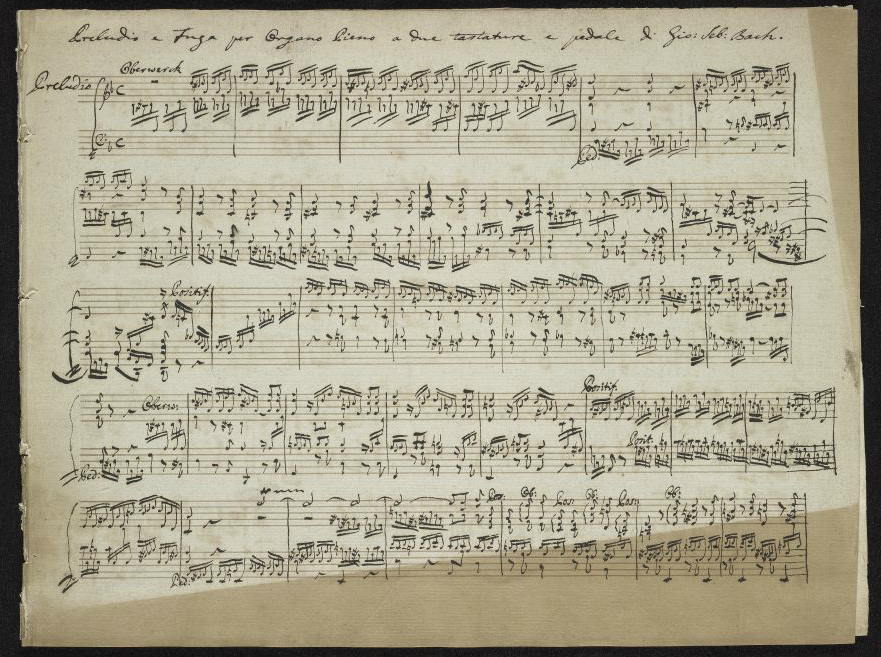

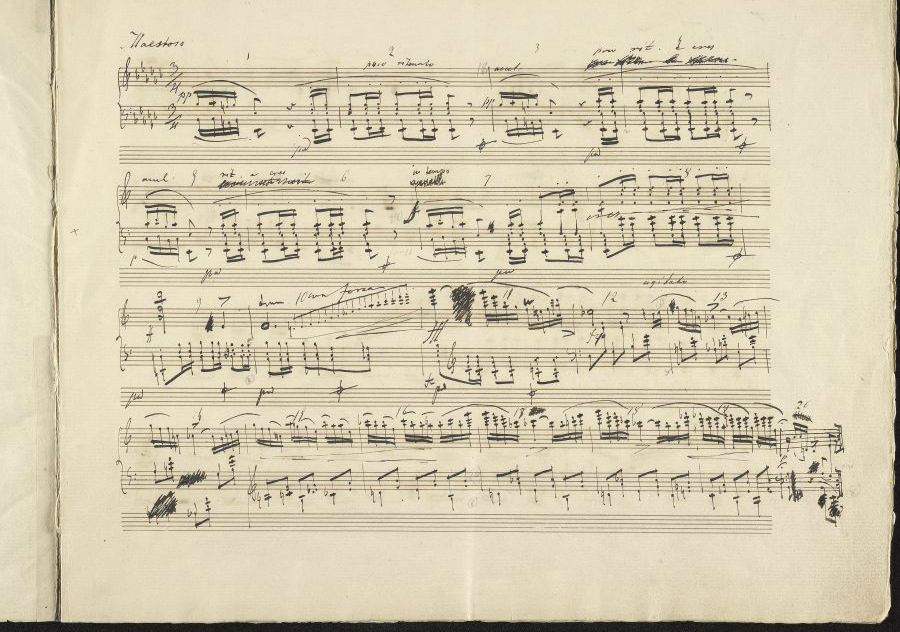

Wagner—musicologists and historians would say—also saw the future, and helped design it through his unwitting posthumous influence on Hitler. The composer’s famed theory and practice of what he called Gesamtkunstwerk, the “total work of art,” anticipate the massive spectacles of 20th century totalitarian aesthetics and the mythological dimensions of 20th century fascism. Wagner called his work the “Music of the Future,” happily appropriating a term critics used to deride his Romantic nationalism. But Wagner’s cultural influence is much, much broader than its most damning association, including his formative influence on Nietzsche.

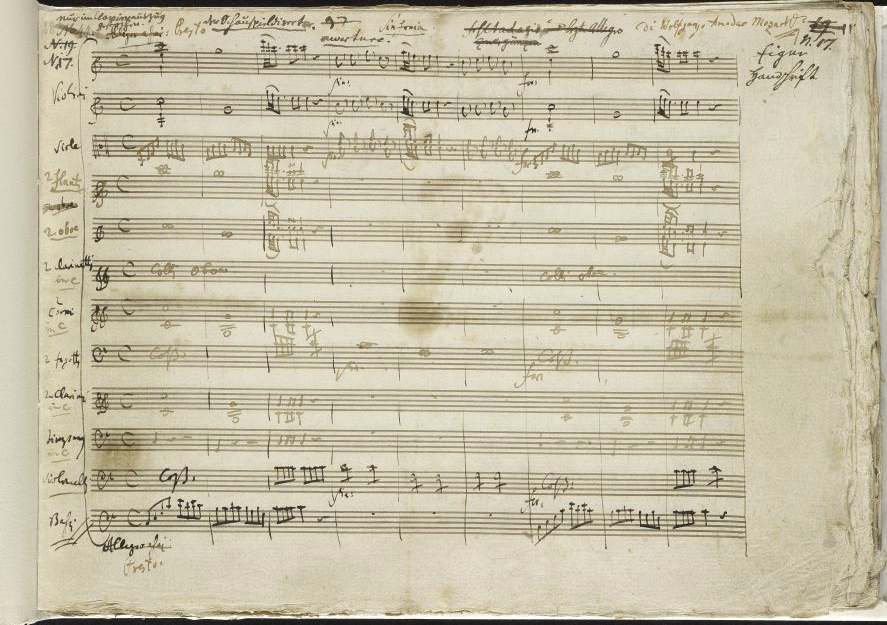

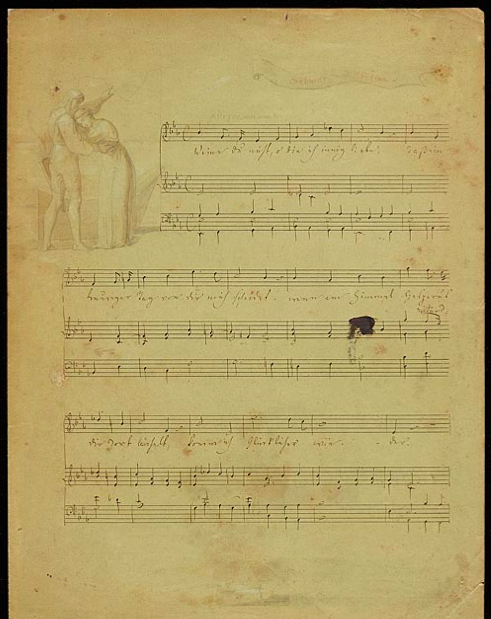

Wagner’s greatest achievement, Der Ring des Nibelungen—referred to as the Ring Cycle—inspired J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and scored the “Ride of the Valkyries” scene in Apocalypse Now. Loony Tunes’ “Kill the Wabbit” spoofed the Ring Cycle, and became an entire generation’s “first, and often only exposure to opera,” as Ayun Halliday noted here recently. The Ring Cycle’s overwhelming demonstration of the Gesamtkunstwerk is a thing to behold, and you can see it here performed in full, all four parts, “15 hours of epic opera” courtesy of BBC Arts and The Space. The film here, by Opera North, comes from live performances in Leeds in 2016. At the top, see Das Rheingold, below it Die Walküre, just above Siegfried, and below Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods”).

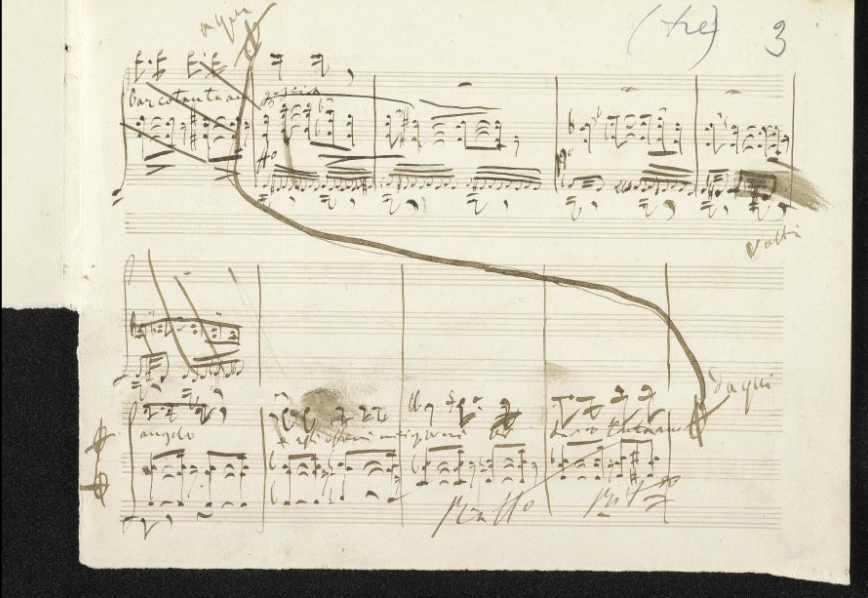

So what should we make of Wagner’s music, given its unavoidable relationship to wars of domination (against even “Wabbits”)? If we are to heed some of his critics, we might think of him as a 19th century Michael Bay. Mark Twain is rumored to have called Wagner’s music “better than it sounds”—though it turns out the quote actually comes from humorist Edgar Wilson. Twain did write that he enjoyed “the first act of everything Wagner created,” but “after two acts I have gone away physically exhausted.” Samuel Beckett, in a gem of a paragraph, called Wagner’s work “clouds on wheels.” But Wagner is also incredibly powerful and often sublime, and his music does inspire the kind of awe that Tolkien and Francis Ford Coppola drew on for their own awe-inspiring work.

< Appreciating Wagner may indeed be an endurance exercise. His booming tales of dwarfs and giants, gods and river-maidens, heroes and, yes, Valkyries, can seem to rumble along several miles above us. The exercise is not for the faint of heart. However, the technology of streaming video can save us from Twain’s fate—you can return here, or to the BBC’s site—as many times as you like without having to take in the massive Der Ring des Nibelungen all in one sitting. And as is always helpful in opera of any length, you can peruse summaries—like this one—when you feel a bit lost in the clouds. Or, for a truly surreal condensed Wagnerian experience, watch the video above of “four and a half hours of opera in one minute.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness