We’ve told you about a fair few vintage video games that you can play free online. Here’s another one to add to your collection.

Back in 1985, Douglas Adams teamed up with Infocom’s Steve Meretzky to create an interactive fiction video game based on The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Designed before graphic-intensive video games really hit their stride, the original Hitchhiker’s Guide game (watch an unboxing above) was played with text commands on the Apple II, Macintosh, Commodore 64, CP/M, DOS, Amiga, Atari 8‑bit and Atari ST platforms. And it found instant success. The adventure game sold 400,000 copies, making it one of the best-selling games of its time, and it was named the “Game Of The Year” by various magazines.

In 2004, the BBC released on its website a 20th anniversary version of the game, and then an enhanced 30th anniversary version last year. Before you start playing, you will need to register for an account with the BBC, and then you would be wise to read the instructions, which begin with these words:

The game remains essentially unchanged and the original writing by Douglas Adams remains untouched. It is still played by entering commands and pressing return. Then read the text, follow your judgement and you will probably be killed an inordinate number of times.

Note: The game will kill you frequently. If in doubt, before you make a move please save your game by typing “Save” then enter. You can then restore your game by typing “Restore” then enter. This should make it slightly less annoying getting killed as you can go back to where you were before it happened. You’ll need to be signed in for this to work. You can sign in or register by clicking the BBCiD icon next to the BBC logo in the top navigation bar.

You can find some important game hints here, or watch a walk-through on YouTube here.

Enjoy.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Back to Bed: A New Video Game Inspired by the Surreal Artwork of Escher, Dali & Magritte

Play the Twin Peaks Video Game: Retro Fun for David Lynch Fans

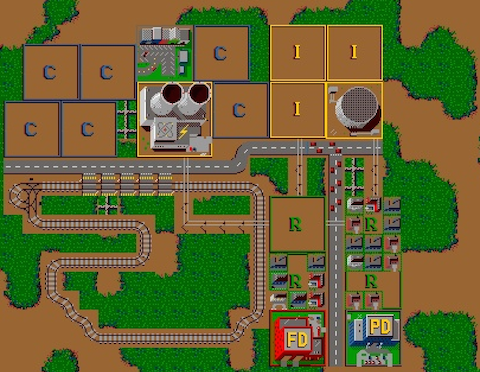

The Internet Arcade Lets You Play 900 Vintage Video Games in Your Web Browser (Free)