Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Few would argue against the claim that Fyodor Dostoevsky, author of such bywords for literary weightiness as Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov, mastered the novel, even by the formidable standards of 19th-century Russia. But if you look into his papers, you’ll find that he also had an intriguing way with pen and ink outside the realm of letters — or, if you like, deep inside the realm of letters, since to see drawings by Dostoevsky, you actually have to look within the manuscripts of his novels.

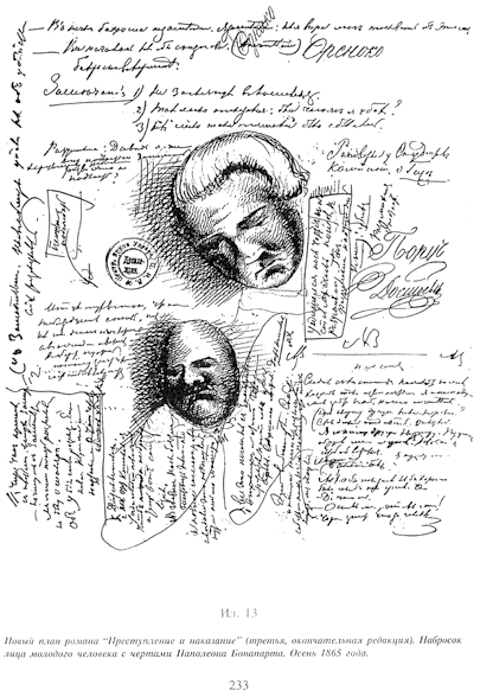

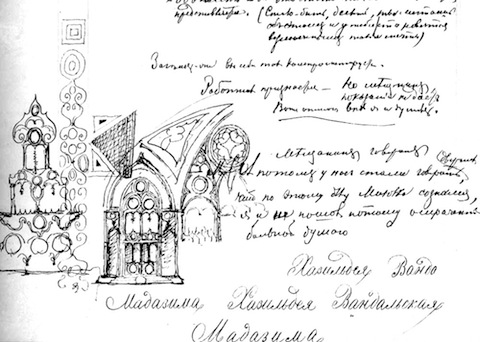

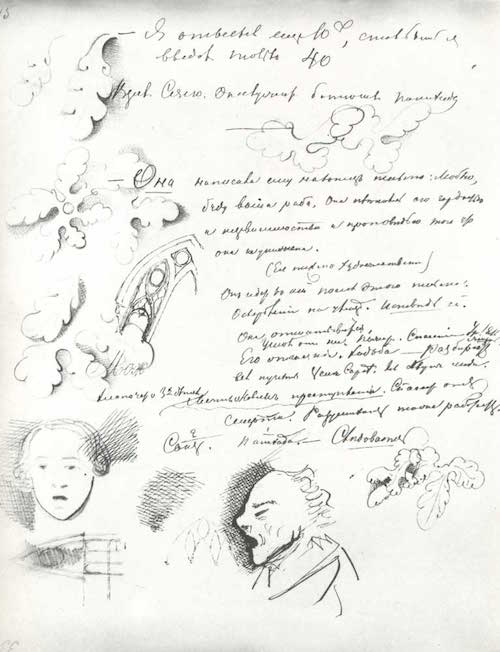

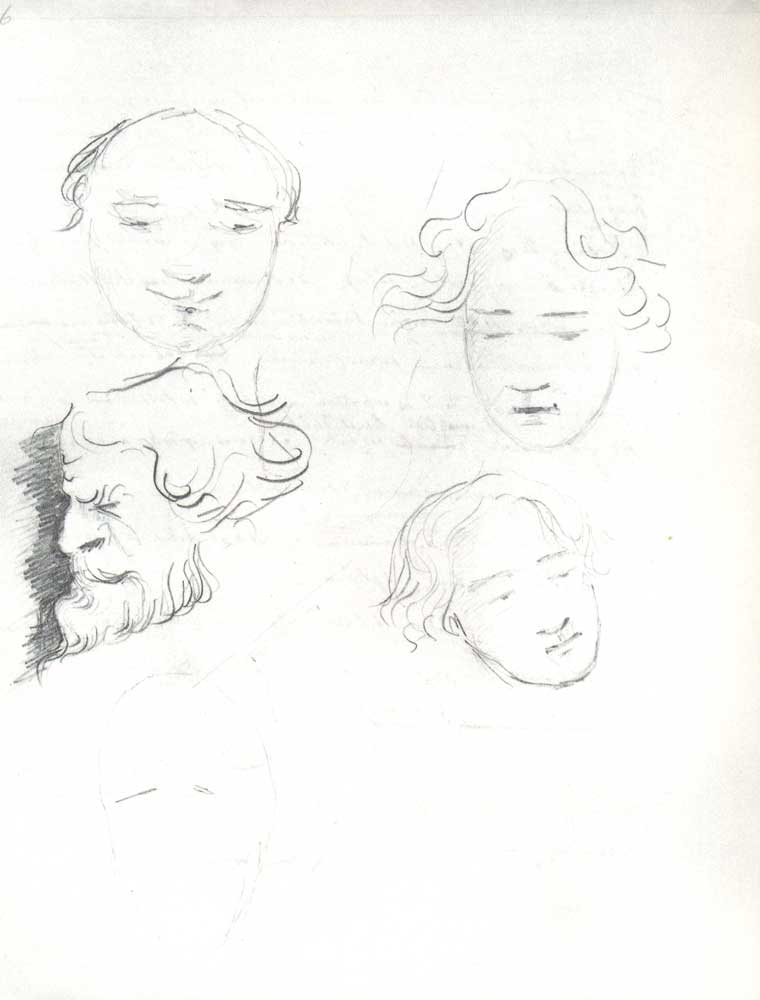

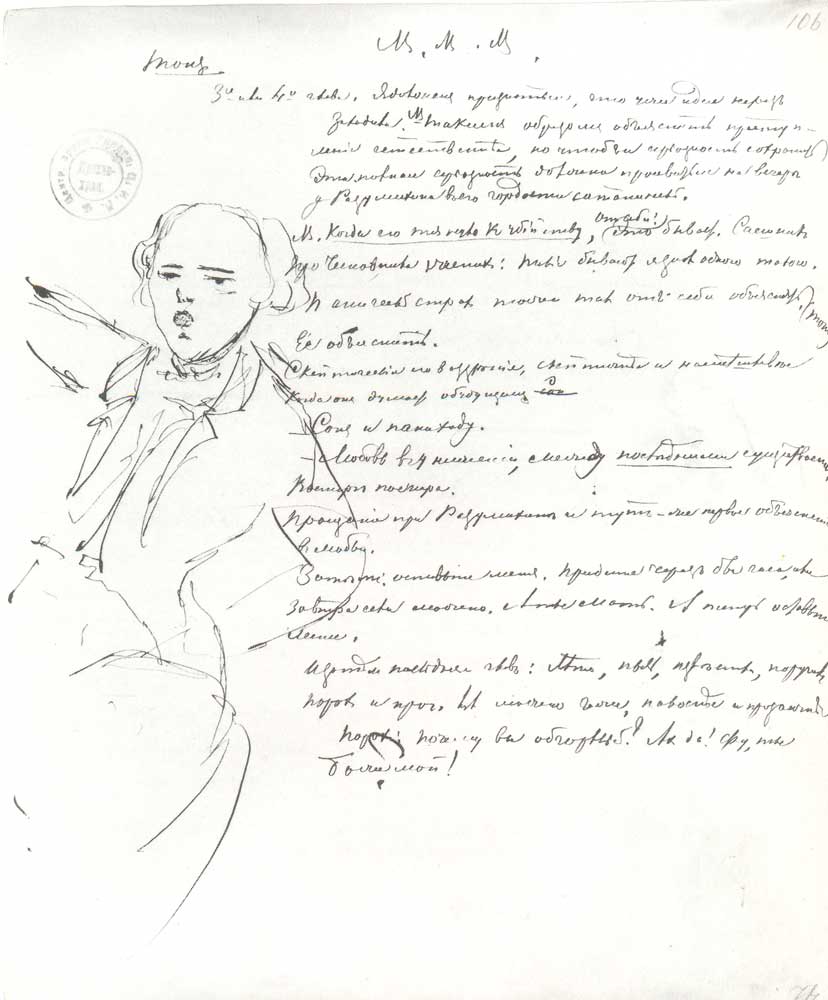

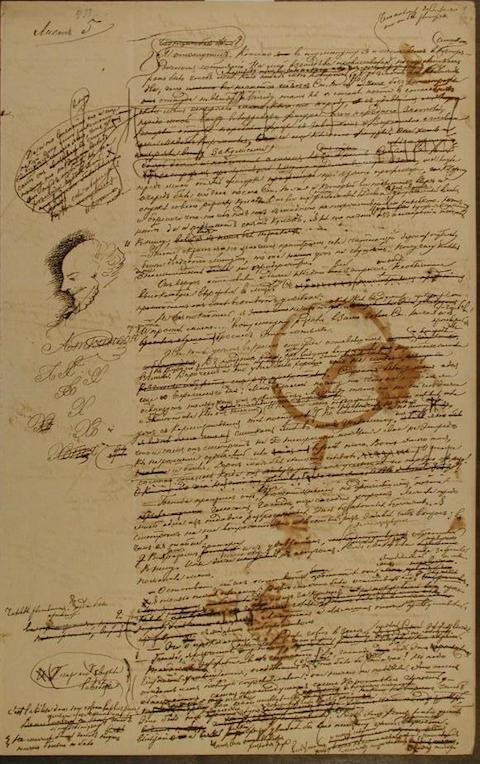

Above, we have a page from Crime and Punishment into which a pair of solemn faces (not that their mood will surprise enthusiasts of Russian literature) found their way. Just below, you’ll find examples from the same manuscript of his pen turning toward the ornamental and architectural while he “created his fiction step by step as he lived, read, remembered, reprocessed and wrote,” as the exhibition of “Dostoyevsky’s Doodles” at Columbia University’s Harriman Institute of Russian, Eurasian, and East European Studies put it.

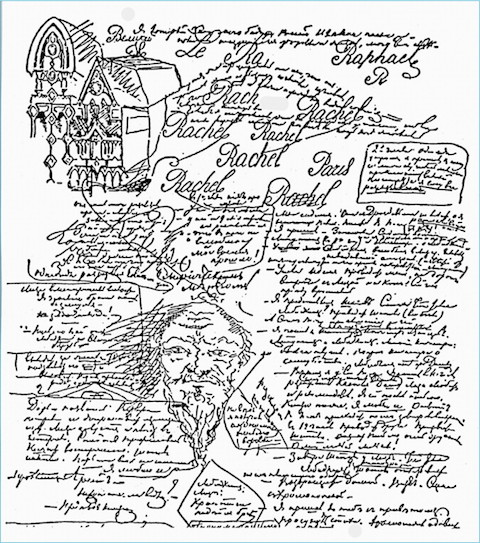

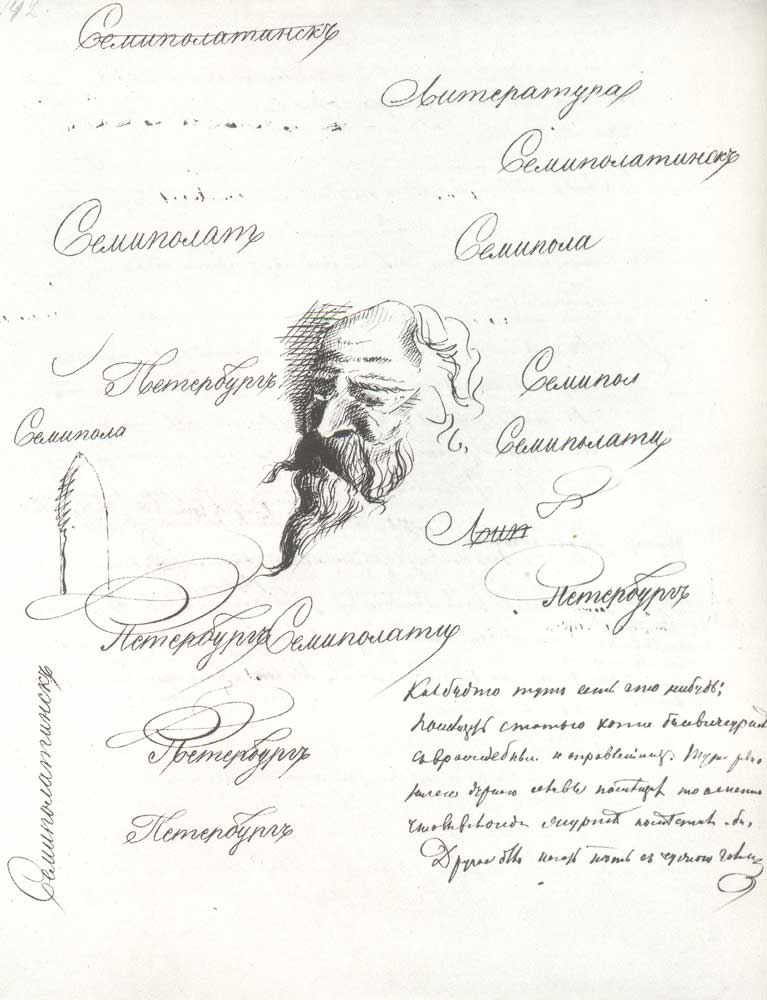

According to the exhibition description, Dostoevsky’s notes to himself “represent that key moment when the accumulated proto-novel crystallized into a text. Like many of us, Dostoevsky doodled hardest when the words came slowest.” Some of Dostoevsky’s character descriptions, argues scholar Konstantin Barsht, “are actually the descriptions of doodled portraits he kept reworking until they were right.” He didn’t just do so during the writing of Crime and Punishment, either; below we have a page of The Devils that combines the human, the architectural, and the calligraphic, apparently the three main avenues through which Dostoevsky pursued the doodler’s art.

Even if you would personally argue against his claim to greatness (and thus side with his countryman, colleague in literature, and fellow part-time artist Vladimir Nabokov, who found him a “mediocre” writer given to “wastelands of literary platitudes”), surely you can enjoy the charge of pure creation you feel from witnessing his textual mind interact with his visual one. Works by Dostoevsky can be found in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.

Related Content:

Albert Camus Talks About Adapting Dostoyevsky for the Theatre, 1959

Nabokov Makes Editorial Improvements to Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.

Read More...Dostoevsky Draws Doodles of Raskolnikov and Other Characters in the Manuscript of Crime and Punishment

Like many of us, Russian literary great Fyodor Dostoevsky liked to doodle when he was distracted. He left his handiwork in several manuscripts—finely shaded drawings of expressive faces and elaborate architectural features. But Dostoevsky’s doodles were more than just a way to occupy his mind and hands; they were an integral part of his literary method. His novelistic imagination, with all of its grand excesses, was profoundly visual, and architectural.

“Indeed,” writes Dostoevsky scholar Konstantin Barsht, “Dostoevsky was not content to ‘write’ and ‘take notes’ in the process of creative thinking.” Instead, in his work “the meaning and significance of words interact reciprocally with other meanings expressed through visual images.” Barsht calls it “a method of work specific to the writer.” We’ve shared a few of those manuscript pages before, including one with a doodle of Shakespeare.

Now we bring you a few more pages of doodles from the author of Crime and Punishment, a novel that, perhaps more so than any of his others, offers such vivid descriptions of its characters that I can still clearly remember the pictures I had of them in my mind the first time I read it in high school.

My visualizations of the angry, desperate student Raskolnikov and the sleazy sociopathic Svidrigailov do not exactly resemble the faces doodled at the the top of the post, but that is how their author saw them, at least in this early, manuscript stage of the novel.

The other faces here may be those of Sonya, police investigator Porfiry Petrovich, recidivist alcoholic father Semyon Marmelodov, and other characters in the novel, though it’s not clear exactly who’s who.

Dostoevsky had much in common with his novel’s protagonist when he began the novel in 1865. Reduced to near-destitution after gambling away his fortune, the writer was also in desperate straits. The story, writes literary critic Joseph Franks, was “originally conceived as a long short story or novella to be written in the first person,” like the feverish novella Notes From the Underground. In Dostoevsky’s manuscript notebooks, “extensive fragments of this original work are to be found here intact.”

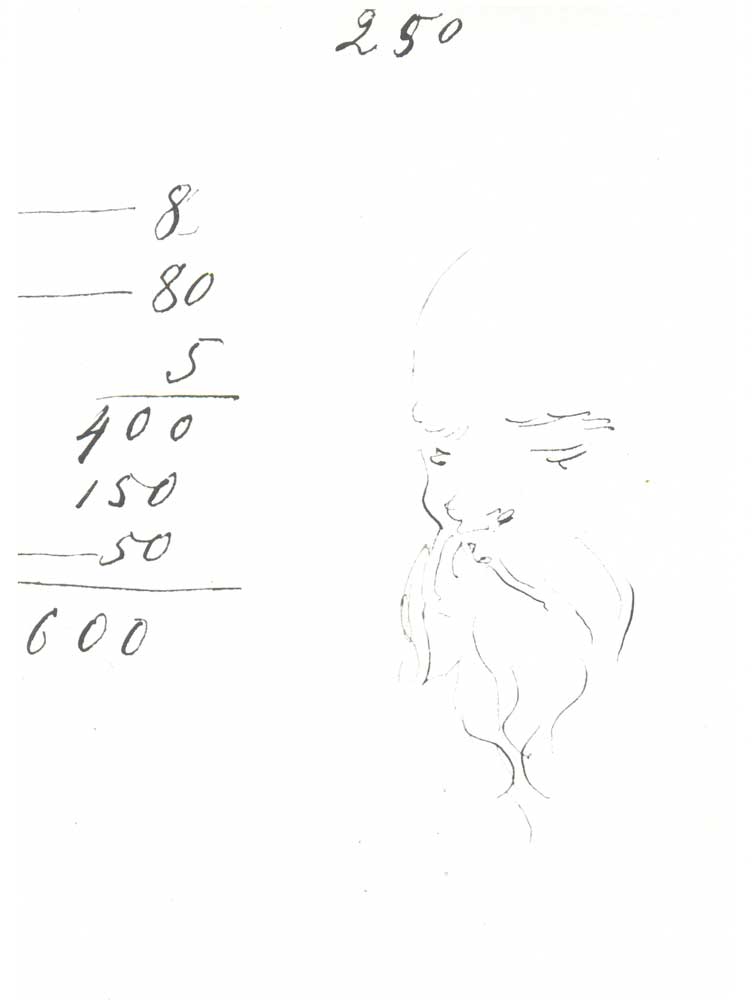

Franks quotes scholar Edward Wasiolek, who published a translation of the notebooks in 1967: “They contain drawings, jottings about practical matters, doodling of various sorts, calculations about pressing expenses, sketches, and random remarks.” In short, “Dostoevsky simply flipped his notebooks open any time he wished to write,” or to practice his calligraphy, as he does on many pages.

The pages of the Crime and Punishment notebooks resemble all of the manuscript pages of his novels in their ornamental haphazardness. You can see many more examples from novels like The Idiot, The Possessed, and A Raw Youth at the Russian site Culture, including the sketchy self portrait below, next to a few sums that indicate the author’s perpetual preoccupation with his troubled economic affairs.

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Dostoevsky Draws a Picture of Shakespeare: A New Discovery in an Old Manuscript

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Animated Dostoevsky: Two Finely Crafted Short Films Bring the Russian Novelist’s Work to Life

You can experience Dostoevsky in the original. You can experience Dostoevsky in translation. Or how about an experience of Dostoevsky in animation? Today we’ve rounded up two particularly notable examples of that last, both of which take up their unconventional project of adaptation with suitably unconventional animation techniques. At the top of the post, we have the first part (and just below we have the second) of Dostoevsky’s story “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man,” re-imagined by Russian animator Alexander Petrov.

The animation, as Josh Jones wrote here in 2014, “uses painstakingly hand-painted cells to bring to life the alternate world the narrator finds himself navigating in his dream. From the flickering lamps against the dreary, darkened cityscape of the ridiculous man’s waking life to the shifting, sunlit sands of the dreamworld, each detail of the story is finely rendered with meticulous care.” A haunting visual style for this haunting piece of late Dostoevsky in full-on existentialist mode.

Just below, you can see a longer and more ambitious adaptation of one of Dostoevsky’s much longer, much more ambitious works: Crime and Punishment. This half-hour animated version by Polish filmmaker Piotr Dumala, Mike Springer wrote here in 2012, gets “told expressionistically, without dialogue and with an altered flow of time. The complex and multi-layered novel is pared down to a few central characters and events,” all of them portrayed with a form of labor-intensive “destructive animation” in which Dumala engraved, painted over, and then re-engraved each frame on plaster, a method where “each image exists only long enough to be photographed and then painted over to create a sense of movement.”

If you’d now like to plunge into Dostoevsky’s literary world and find out if it compels you, too, to create strikingly unconventional animations — or any other sort of project inspired by the writer’s epic grappling with life’s greatest, most troubling themes — you can do it for free with our collection of Dostoevsky eBooks and audiobooks.

Related Content:

Watch a Hand-Painted Animation of Dostoevsky’s “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Dostoevsky Draws a Picture of Shakespeare: A New Discovery in an Old Manuscript

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Dostoevsky Draws a Picture of Shakespeare: A New Discovery in an Old Manuscript

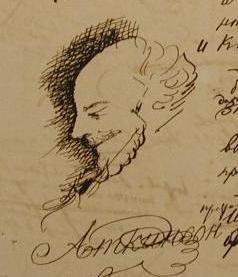

Dostoevsky, a doodler? Surely not! Great Russian brow furrowed over the meaning of love and hate and faith and crime, diving into squalid hells, ascending to the heights of spiritual ecstasy, taking a gasp of heavenly air, then back down to the depths again to churn out the pages and hundreds of character arcs—that’s Dostoevsky’s style. Doodles? No. And yet, even Dostoevsky, the acme of literary seriousness, made time for the odd pen and ink caricature amidst his bouts of existential angst, poverty, and ill health. We’ve shown you some of them before—indeed, some very well rendered portraits and architectural drawings in the pages of his manuscripts. Now, just above, see yet another, a recently discovered tiny portrait of Shakespeare in profile, etched in the margins of a page from one of his angstiest novels, The Possessed, available in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices.

Annie Martirosyan in The Huffington Post points out some family resemblance between the Shakespeare doodle and the famous brooding oil portrait of Dostoevsky himself, by Vasily Perov. She also notes the ring stain and sundry drips over the “hardly legible… scribbles” and “marginalia… scattered naughtily across the page” is from the author’s tea. “Feodor Mikhailovich was an avid tea drinker,” and he would consume his favorite beverage while walking “to and fro in the room and mak[ing] up his characters’ speeches out loud….” Can’t you just see it? Under the drawing (see it closer in the inset)—in one of the many examples of the author’s painstaking handwriting practice—is the name “Atkinson.”

Martirosyan sums up a somewhat complicated academic discussion between Dostoevsky experts Vladimir Zakharov and Boris Tikhomirov about the source of this name. This may be of interest to literary specialists. But perhaps it suffices to say that both scholars “have now confirmed the authenticity of the image as Dostoevsky’s drawing of Shakespeare,” and that the name and drawing may have no conceptual connection. It’s also further proof that Dostoevsky, like many of us, turned to making pictures when, says scholar Konstantin Barsht—whom Colin Marshall quoted in our previous post—“the words came slowest.” In fact, some of the author’s character descriptions, Barsht claims, “are actually the descriptions of doodled portraits he kept reworking until they were right.”

So why Shakespeare? Perhaps it’s simply that the great psychological novelist felt a kinship with the “inventor of the human.” After all, Dostoevsky has been called, in those memorable words from Count Melchoir de Vogue, “the Shakespeare of the lunatic asylum.”

h/t OC reader Nick

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Watch a Hand-Painted Animation of Dostoevsky’s “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Why You Should Read The Master and Margarita: An Animated Introduction to Bulgakov’s Rollicking Soviet Satire

Which are the essential Russian novels? Quite a few undeniable contenders come to mind right away: Fathers and Sons, Crime and Punishment, War and Peace, Anna Karenina, The Brothers Karamazov, Dr. Zhivago, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. But among serious enthusiasts of Russian literature, novels don’t come much less deniable than The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov’s tale of the Devil’s visit to Soviet Moscow in the 1930s. This “surreal blend of political satire, historical fiction, and occult mysticism,” as Alex Gendler describes it in the animated TED-Ed video above, “has earned a legacy as one of the 20th century’s greatest novels — and one of its strangest.”

The Master and Margarita consists of two parallel narratives. In the first, “a meeting between two members of Moscow’s literary elite is interrupted by a strange gentleman named Woland, who presents himself as a foreign scholar invited to give a presentation on black magic.” Then, “as the stranger engages the two companions in a philosophical debate and makes ominous predictions about their fates, the reader is suddenly transported to first-century Jerusalem,” where “a tormented Pontius Pilate reluctantly sentences Jesus of Nazareth to death.”

The novel oscillates between the story of the historical Jesus — though not quite the one the Bible tells — and that of Woland and his entourage, which includes an enormous cat named Behemoth with a taste for chess, vodka, wisecracks, and firearms. Dark humor flows liberally from their antics, as well as from Bulgakov’s depiction of “the USSR at the height of the Stalinist period. There, artists and authors worked under strict censorship, subject to imprisonment, exile, or execution if they were seen as undermining state ideology.”

The devilish Woland plays this overbearing bureaucratic life like a fiddle, and “as heads are separated from bodies and money rains from the sky, the citizens of Moscow react with petty-self interest, illustrating how Soviet society bred greed and cynicism despite its ideals.” Such content would naturally render a book unpublishable at the time, and though Bulgakov’s earlier satire The Heart of a Dog (in which a surgeon transplants human organs into a dog and then insists he behave as a human) circulated in samizdat form, he couldn’t even complete The Master and Margarita before his death in 1940.

“Bulgakov’s experiences with censorship and artistic frustration lend an autobiographical air to the second part of the novel, when we are finally introduced to its namesake,” says Gendler. “The Master is a nameless author who’s worked for years on a novel but burned the manuscript after it was rejected by publishers — just as Bulgakov had done with his own work. Yet the true protagonist is the Master’s mistress Margarita,” whose “devotion to her lover’s abandoned dream bears a strange connection to the diabolical company’s escapades — and carries the story to its surreal climax.”

In the event, a censored version of The Master and Margarita was first published in the 1960s, and an as-complete-as-possible version eventually appeared in 1973. Against the odds, the manuscript that Bulgakov left behind survived him to become a masterpiece that has inspired not just other Russian writers, but creators like the Rolling Stones, Patti Smith, and (in a perhaps less than safe-for-work manner) H.R. Giger as well. Perhaps the author himself had some premonition of the book’s potential: manuscripts, as he famously has Woland say to the Master, don’t burn.

Looking for free, professionally-read audio books from Audible.com? (This could include The Master and Margarita.) Here’s a great, no-strings-attached deal. If you start a 30 day free trial with Audible.com, you can download two free audio books of your choice. Get more details on the offer here.

Related Content:

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, Animated in Two Minutes

Patti Smith’s Musical Tributes to the Russian Greats: Tarkovsky, Gogol & Bulgakov

Why Should We Read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451? A New TED-Ed Animation Explains

Why You Should Read One Hundred Years of Solitude: An Animated Video Makes the Case

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Museum Discovers Math Notebook of an 18th-Century English Farm Boy, Adorned with Doodles of Chickens Wearing Pants

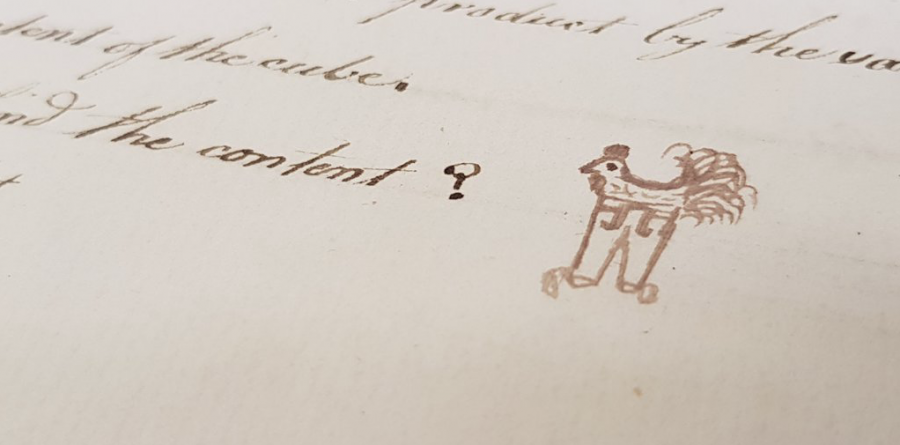

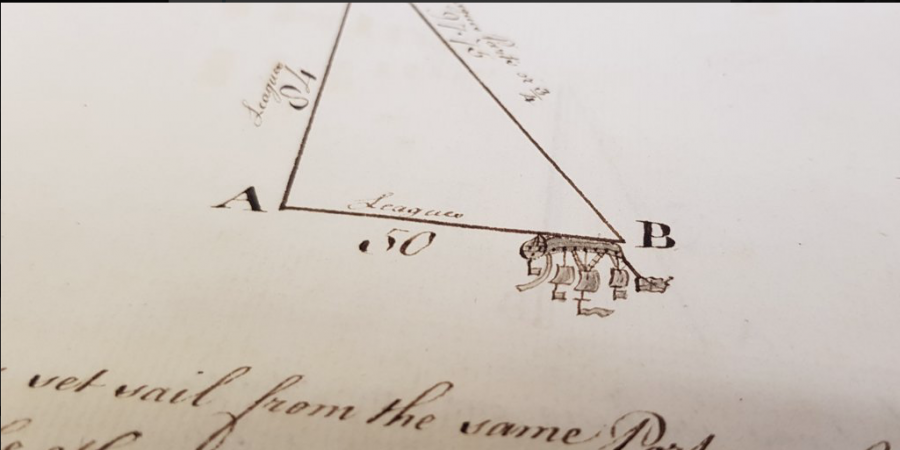

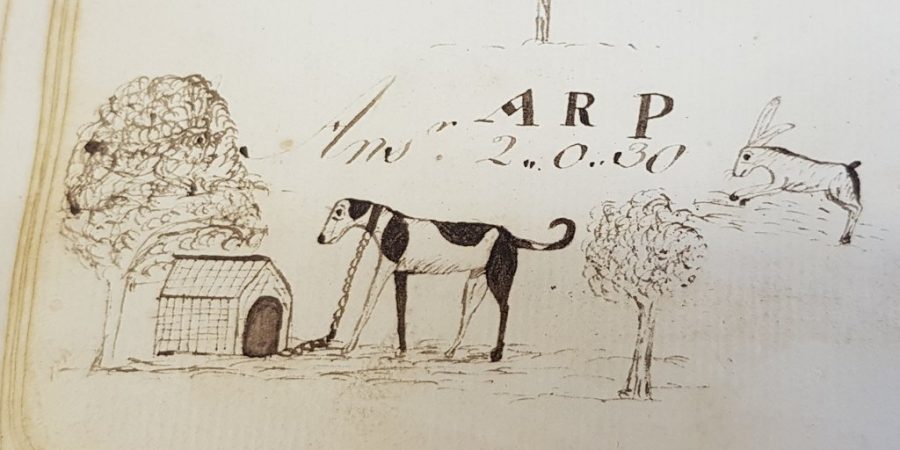

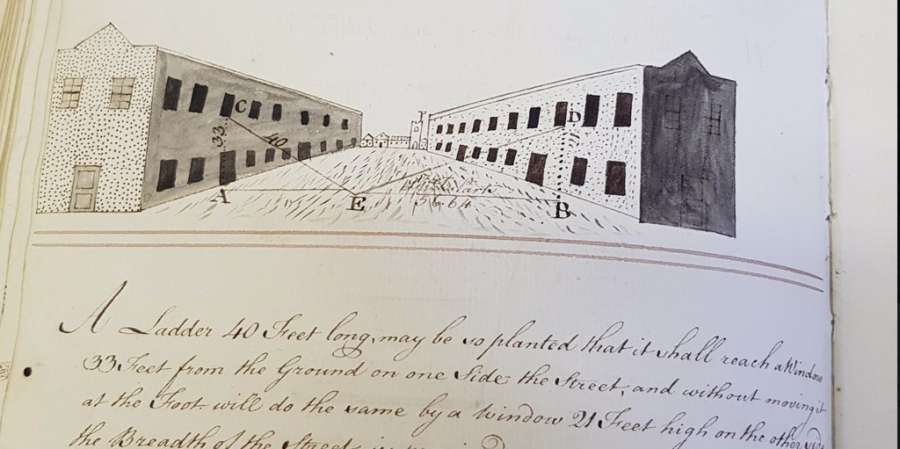

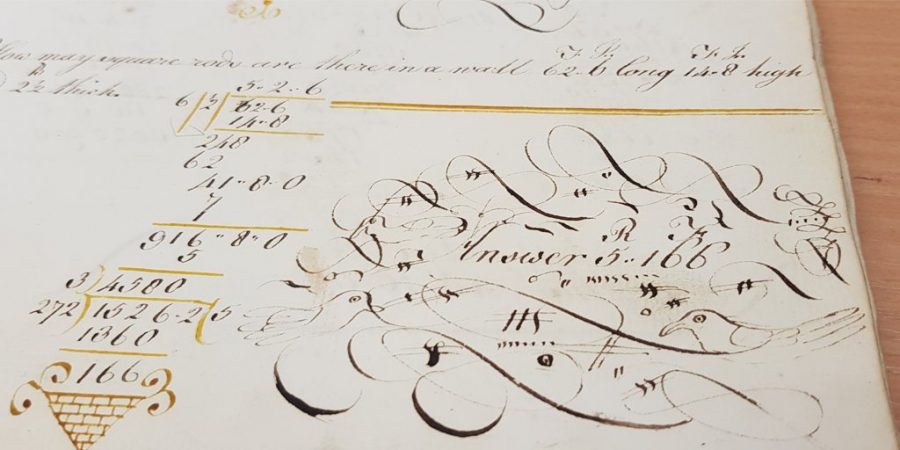

We are trained by tradition to think of history as a series of great men’s (and some women’s) lives, of great wars and royal successions, conquests and tragic defeats, revolutions and world-changing discoveries. The ordinary, everyday lives of ordinary, everyday people seem tedious and unremarkable by comparison. But archivists know better. Their jobs are not glamorous, but what they lack in fame or academic sinecures, they make up for with chance discoveries of the kind that we see here—doodles in the 1784 math notebook of one Richard Beale, a 13-year-old farm boy from rural Kent, England.

The archivists at the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) were so excited about this find they made a Twitter thread about it, explaining its provenance in a bundle of eighteenth-century farm diaries, which “are a lot like normal diaries but with more cows.”

The museum’s program manager, Adam Koszary, has a good ear for the medium, tweeting out other witticisms about Richard’s adventures in taking notes: “But, like every teenager, mathematics couldn’t fill the void of Richard’s heart. Richard doodled.” He drew pictures of his dog, incorporated drawings of ships into his equations, and impeccably illustrated his word problems.

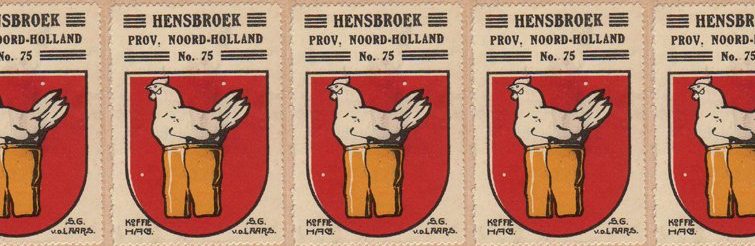

One can almost imagine the listicle: “Rural 18th-Century English Folk: They’re Just Like Us!” They think about their pets a lot. They draw when they get bored. They doodle tiny sketches of chickens in pants…Wait what? Yes, a chicken in trousers appears among Richard’s doodles, one of the many charming features that landed MERL’s story in The Guardian and garnered famous fans like JK Rowling. Like seemingly everything on the internet, the chicken in pants has sparked conspiracy theories, such as “Why do the trousers appear to be solid like Wallace’s in The Wrong Trousers?” and “Was Richard Beale acquainted with the town of Hensbroek in the Netherlands?”

These questions, writes Guy Baxter, associate director of archive services at MERL, are only partly tongue-in-cheek. The Dutch town of Hensbroek, does indeed have a coat of arms featuring a chicken in pants that bears a very close resemblance to Richard’s drawing, though it is entirely unlikely that Richard ever traveled to the Netherlands. The arms of Hensbroek “are a famous example of ‘canting’, which uses a pun on a name to inspire the design,” notes Baxter. (Hensbroek literally means “hens pants.”) The origin of Richard’s design is more mysterious. “It is possible that he knew about canting arms,” Baxter admits. “Or maybe he just had a vivid imagination.”

The little story of Richard Beale and his math homework doodles shows us something about our fractured, fragmented world and the anxious, divided lives we seem to lead online, says Ollie Douglas, curator of MERL’s object collections: “Social media is awash with highly personalized engagements and commentaries on the world…. You only need to look through the responses to this single Twitter thread (and that fact that a readymade chicken-in-trousers gif was available for us to shamelessly retweet) to see that the messy complexity of our world is still being shared and that we are all still doodlers at heart.”

Follow the Museum of English Rural Life for updates to this story.

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hear a BBC Radio Drama of Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: Streaming Free for a Limited Time

A quick heads up: For the next two weeks, you can stream a BBC Radio 4 dramatization of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s final novel, The Brothers Karamazov. Published between January 1879 and November 1880, the philosophical novel has influenced generations of readers–certainly me, maybe you, and then some other notable figures like Einstein, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Freud and more. The radio dramatization is truncated, just 5 hours, whereas most complete versions run 34 hours. (Find those in our collection of Free Audio Books. Or get a professionally-read version on Audible.com, by checking out Audible’s 30-day free trial program.) Below, you can find the installments of the BBC radio drama.

- Episode 1: Russia, 1880: The unpredictable Fyodor Karamazov and his sons are reunited to discuss Dmitry’s inheritance. Stars Roy Marsden.

- Episode 2: As Alyosha attends to dying Father Zosima, relations between Dmitry and his father turn ever more dangerous. Stars Paul Hilton.

- Episode 3: Following a violent encounter at the Karamazov home, Dmitry flees the town in search of Grushenka. Stars Paul Hilton.

- Episode 4: As Dmitry goes on trial for murder, Alyosha desperately seeks proof of his innocence. Stars Paul Hilton and Carl Prekopp.

- Episode 5: Following Ivan’s dramatic appearance at his brother’s trial, Katerina prepares to deal Dmitry a fatal blow. Stars Paul Hilton.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Life & Literature Introduced in a Monty Python-Style Animation

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Free Online Literature Courses

Read More...Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Life & Literature Introduced in a Monty Python-Style Animation

“You know how earlier we were talking about Dostoyevsky?” asks David Brent, Ricky Gervais’ iconically insecure paper-company middle-manager central to the BBC’s original The Office. “Oh, yeah?” replies Ricky, the junior employee who had earlier that day demonstrated a knowledge of the influential Russian novelist apparently intimidating to his boss. “Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky. Born 1821. Died 1881,” recites Brent. “Just interested in him being exiled in Siberia for four years.” Ricky admits to not knowing much about that period of the writer’s life. “All it is is that he was a member of a secret political party,” Brent continues, drawing upon research clearly performed moments previous, “and they put him in a Siberian labour camp for four years, so, you know…”

We here at Open Culture know that you wouldn’t stoop to such tactics in an attempt to establish intellectual supremacy over your co-workers — nor would you feel any shame in not having yet plunged into the work of that same Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky, born 1821, died 1881, and the author of such much-taught novels as Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and The Brothers Karamazov (as well as a prolific doodler). “His first major work,” in the posturing words of David Brent, “was Notes from the Underground, which he wrote in St Petersburg in 1859. Of course, my favorite is The Raw Youth. It’s basically where Dostoyevsky goes on to explain how science can’t really find answers for the deeper human need.”

An intriguing position! To hear it explained with deeper comprehension (but just as entertainingly, and also in an English-accented voice), watch this 14-minute, Monty Python-style animated primer from Alain de Botton’s School of Life and read the accompanying article from The Book of Life. Even apart from those years in Siberia, the man “had a very hard life, but he succeeded in conveying an idea which perhaps he understood more clearly than anyone: in a world that’s very keen on upbeat stories, we will always run up against our limitations as deeply flawed and profoundly muddled creatures,” an attitude “needed more than ever in our naive and sentimental age that so fervently clings to the idea – which this great Russian loathed – that science can save us all and that we may yet be made perfect through technology.”

After The School of Life gets you up to speed on Dostoyevsky, you’ll no doubt find yourself able to more than hold your own in any water-cooler discussion of the man whom James Joyce credited with shattering the Victorian novel, “with its simpering maidens and ordered commonplaces,” whom Virginia Woolf regarded as the most exciting writer other that Shakespeare, and whose work Hermann Hesse tantalizingly described as “a glimpse into the havoc.” You may well also find yourself moved even to open one of Dostoyevsky’s intimidatingly important books themselves, whose assessments of the human condition remain as devastatingly clear-eyed as, well, The Office’s.

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Dostoevsky Draws a Picture of Shakespeare: A New Discovery in an Old Manuscript

Albert Camus Talks About Nihilism & Adapting Dostoyevsky’s The Possessed for the Theatre, 1959

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Download 800 free eBooks to your Kindle, iPad/iPhone, computer, smart phone or ereader. Collection includes great works of fiction, non-fiction and poetry, including works by Asimov, Jane Austen, Philip K. Dick, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Neil Gaiman, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Shakespeare, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf & James Joyce. Also please see our collection 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free, where you can download more great books to your computer or mp3 player.

- Aeschylus - Prometheus Bound

- Aesop - Aesop’s Fables

- Andersen, Hans Christian - Andersen’s Fairy Tales

- Anderson, Sherwood — Winesburg, Ohio

- Anonymous - Beowulf

- Anonymous — Epic of Gilgamesh

- Anonymous - The Arabian Nights

- Aquinas, Thomas — Summa Theologiae

- Aristophanes — Lysistrata

- Aristophanes - The Birds

- Aristophanes - The Clouds

- Arnold, Matthew - Culture and Anarchy

- Aristotle — Collected Works

- Aristotle — Nicomachean Ethics

- Aristotle — Physics

- Aristotle - Politics

- Aristotle — The Categories

- Asimov, Isaac — “How People Get New Ideas”

- Asimov, Isaac — “Jokester”

- Asimov, Isaac — “Let’s Get Together”

- Asimov, Isaac - “Living Space”

- Asimov, Isaac — “Silly Asses”

- Asimov, Isaac - “Youth”

- Aurelius, Marcus - Meditations

- Austen, Jane - Emma

- Austen, Jane — Lady Susan

- Austen, Jane - Love and Friendship

- Austen, Jane - Mansfield Park

- Austen, Jane - Northanger Abbey

- Austen, Jane - Persuasion

- Austen, Jane - Pride & Prejudice

- Austen, Jane — Sense & Sensibility

- Ayer, Alfred — Language, Truth and Logic

- Bacon, Sir Francis — Novum Organum

- Balzac, Honoré de - Le Père Goriot

- Barthes, Roland — Incidents

- Basho, Matsuo — Various Poems

- Baudelaire, Charles - Les Fleurs du Mal (in French)

- Baudelaire, Charles - Flowers of Evil (in English)

- Baudelaire, Charles - The Generous Gambler

- Baudelaire, Charles - The Poem of Hashish (translated by Aleister Crowley)

- Barrie, JM- Peter Pan

- Baum, L. Frank - The Wizard of Oz (Vol 1)

- Baum, L. Frank - The Marvelous Land of Oz (Vol 2)

- Baum, L. Frank — Ozma of Oz (Vol 3)

- Baum L. Frank — Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (Vol 4)

- Baum L. Frank — The Road to Oz (Vol 5)

- Baum, L. Frank — The Emerald City of Oz (Vol 6)

- Baum, L. Frank — The Patchwork Girl of Oz (Vol 7)

- Baum, L. Frank — Tik-Tok of Oz (Vol 8)

- Baum, L. Frank - The Scarecrow of Oz (Vol 9)

- Baum, L. Frank — Rinkitink in Oz (Vol 10)

- Baum L. Frank — The Lost Princess of Oz (Vol 11)

- Baum L. Frank — The Tin Woodman of Oz (Vol 12)

- Baum L. Frank — The Magic of Oz (Vol 13)

- Baum, L. Frank — Glinda of Oz (Vol 14)

- Beckett, Samuel - Waiting for Godot

- Benjamin, Walter — “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”

- Bergerac, Cyrano de — Voyage to the Moon

- Berkeley, George — Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous

- Berlin, Isaiah - Concepts and Categories

- Berlin, Isaiah - The Arts in Russia Under Stalin

- Berryman, John - Card Trick

- Berryman, John — Modus Vivendi

- Berryman, John — The Right Time

- Berryman, John — Trouble With Telstar

- Berryman, John — Vigorish

- Blake, William — Songs of Innocence and of Experience

- Blake, William - Selected Poems

- Boethius — Consolation of Philosophy

- Borges, Jorge Luis — “The Library of Babel”

- Bradbury, Ray — “I See You Never”

- Bradbury, Ray — “The Jar”

- Bradbury, Ray — “The Last Night of the World”

- Bronte, Charlotte - Jane Eyre

- Bronte, Emily - Wuthering Heights

- Buchan, John - The Thirty Nine Steps

- Bukowski, Charles — Archive of Poems and Letter Manuscripts

- Bukowski, Charles — His Last (Faxed) Poem

- Bukowski, Charles — Dostoevsky

- Burke, Edmund - Reflections on the Revolution in France

- Burke, Edmund - On the Sublime and Beautiful

- Burckhardt, Jacob- The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy

- Burroughs, Edgar Rice - A Princess of Mars

- Calvino, Italo - “Distance to the Moon”

- Calvino, Italo — “The Daughters of the Moon”

- Calvino, Italo — “Why Read the Classics?”

- Camus, Albert — The Stranger

- Carroll, Lewis - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Carroll, Lewis — Symbolic Logic

- Carroll, Lewis — The Game of Logic

- Carroll, Lewis - Through the Looking-Glass

- Carver, Raymond — “Beginners” (early draft of “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love”)

- Carver, Raymond - “Cathedral”

- Cervantes - Don Quixote

- iPad/iPhone (Vol 1 — Vol 2) — Kindle + Other Formats — Read Online Now

- Chandler, Raymond - “The Simple Art of Murder”

- Chaucer - Canterbury Tales

- Chekhov, Anton - Plays

- Chekhov, Anton — Collected Stories

- Chekhov, Anton - The Kiss

- Chekhov, Anton - The Lady with the Dog

- Chekhov, Anton — The Chorus Girl and Other Stories (by Constance Garnett)

- Chekhov, Anton - Uncle Vanya

- Chomsky, Noam — Deterring Democracy

- Chomsky, Noam — Excerpts from Powers and Prospects: Reflections on Human Nature and the Social Order

- Chomsky, Noam — Keeping the Rabble in Line

- Chomsky, Noam — Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies

- Chomsky, Noam — Rethinking Camelot: JFK, the Vietnam War, and U.S. Political Culture

- Chomsky, Noam — Secrets, Lies and Democracy

- Chomsky, Noam — The Prosperous Few and the Restless Many

- Chomsky, Noam — What Uncle Sam Really Wants

- Chomsky, Noam — Year 501: The Conquest Continues

- Chopin, Kate - The Awakening

- Christie, Agatha - The Mysterious Affair at Styles

- Christie, Agatha - The Secret Adversary

- Cicero — Orations

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “Second Dawn”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “The Deep Range”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “The Nine Billion Names of God”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “The Parasite”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “The Star”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “The Stroke of the Sun”

- Clarke, Arthur C. — “A Walk in the Dark”

- Coelho, Paulo - The Way of the Bow

- Coelho, Paulo - Warrior of the Light

- Coelho, Paulo - Assorted Texts (in different languages)

- Coleridge, Samuel - Ancient Mariner and Select Poems

- Confucius — The Analects

- Confucius — The Great Learning

- Conrad, Joseph - Lord Jim

- Conrad, Joseph - Heart of Darkness

- Conrad, Joseph — Nostromo

- Conrad, Joseph - The Secret Agent

- Conrad, Joseph - Victory

- Crane, Stephen - The Red Badge of Courage

- Crowley, Aleister — Book of Law

- Crowley, Aleister — Household Gods

- Cummings E.E. — The Enormous Room

- da Vinci, Leonardo — A Treatise on Painting

- da Vinci, Leonardo — Anatomy Drawings

- Dante - The Divine Comedy

- Dante — The Divine Comedy (Digital Version from Columbia University)

- Dante — Intertextual Dante

- Darwin, Charles - On the Origin of Species

- Darwin, Charles — The Descent of Man

- Darwin, Charles — The Voyage of the Beagle

- Defoe, Daniel - Robinson Crusoe

- Denton, Bradley — Buddy Holly is Alive and Well on Ganymede (Background)

- Derrida, Jacques — “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences”

- Descartes, Rene - Discourse on the Method

- Dewey, John - Democracy & Education

- Diaz, Junot — 7 Free Stories

- Dick, Philip K. — “Adjustment Team”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Beyond the Door”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Beyond Lies the Wub”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Breakfast at Twilight”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Exhibit Piece”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Foster You’re Dead”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Human Is”

- Dick, Philip K. — “James P. Crow”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Meddler”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Mr. Spaceship”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Piper in the Woods”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Progeny”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Prominent Author”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Sales Pitch”

- PDF — eText

- Dick, Philip K. — “Second Variety”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Shell Game”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Small Town”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Souvenir”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Survey Team”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Crawlers”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Crystal Crypt”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Defenders”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Eyes Have It”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Golden Man”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Gun”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Hanging Stranger”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Last of tbe Masters”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Skull”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Turning Wheel”

- Dick, Philip K. — “The Variable Man”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Tony and the Beetles”

- Dick, Philip K. — “Upon the Dull Earth”:

- Dick, Philip K. — “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale”

- Dickens, Charles - A Christmas Carol

- Dickens, Charles - A Tale of Two Cities

- Dickens, Charles - Bleak House

- Dickens, Charles - David Copperfield

- Dickens, Charles - Great Expectations

- Dickens, Charles - Hard Times

- Dickens, Charles — Little Dorrit

- Dickens, Charles - Mystery of Edwin Drood

- Dickens, Charles - Nicholas Nickleby

- Dickens, Charles - Oliver Twist

- Dickens, Charles - Our Mutual Friend

- Dickens, Charles — The Pickwick Papers

- Dickinson, Emily - Poems

- Didion, Joan — 12 Masterful Essays

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - A Raw Youth (Translated by Constance Garnett)

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - Brothers Karamazov

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - Crime and Punishment

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - Notes from the Underground

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - Poor Folk

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor — The Double

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor — “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - The Gambler

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - The Idiot

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - The Possessed

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor - White Nights and Other Stories

- Douglass, Frederick — Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

- Doyle, Arthur Conan - The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

- Doyle, Arthur Conan- The Complete Sherlock Holmes

- Doyle, Arthur Conan — The Hound of Baskerville

- Doyle, Arthur Conan - The Lost World

- Doyle, Arthur Conan - The Poison Belt

- Dreiser, Theodore - An American Tragedy

- Dreiser, Theodore - Sister Carrie

- Dumas, Alexandre - The Count of Monte Cristo

- Dumas, Alexandre - The Man in the Iron Mask

- Dumas, Alexandre - The Three Musketeers

- Durkheim, Emile — Le suicide: Étude de sociologie

- Eliot, Charles - The Harvard Classics (51 Volumes)

- Einstein, Albert — Relativity : The Special and General Theory

- Eisenstein, Sergei — Notes of a Film Director

- Eliot, George - Daniel Deronda

- Eliot, George - Middlemarch

- Eliot, George - Silas Marner

- Eliot, T.S. — Eeldrop and Appleplex

- Eliot, T.S. - Ezra Pound: His Metric and Poetry by T. S. Eliot

- Eliot, T.S. — Four Quartets

- Eliot, T.S. - Poems (Including “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”)

- Eliot, T.S. — The Hollow Men

- Eliot, T.S. — The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

- Eliot, T.S. — The Sacred Wood

- Eliot, T.S. — “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

- Eliot, TS - The Waste Land

- Eisenstein, Sergei — Notes on a Film Director

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo — Essays

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo - The Complete Works

- Erasmus - The Praise of Folly

- Euripides - Medea

- Euripides — The Bacchae

- Faulkner, William - The Collected Stories of William Faulkner

- Faulkner, William — Early Prose and Poetry

- Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert; Sands, Matthew - The Feynman Lectures on Physics

- Volume 1: Read Online Now

- Volume 2: Read Online Now

- Volume 3: Read Online Now

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott — “Babylon Revisited”

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott — “Bernice Bobs Her Hair”

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - Collected Stories

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott — All the Sad Young Men

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - Flappers and Philosophers

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - Tales of the Jazz Age

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - Tender is the Night

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - The Beautiful and Damned

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - The Great Gatsby

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott - This Side of Paradise

- Flaubert, Gustave - Madame Bovary

- Flaubert, Gustave - Salammbo

- Flaubert, Gustave — Three Short Works

- Fontane, Theodor — Effi Briest

- Ford, Madox Ford - The Good Soldier

- Forster, E.M. — A Room with a View

- Forster, E.M. - Howards End

- Forster, E.M. - The Machine Stops

- Foucault, Michel - Die Ordnung des Diskurses

- Franklin, Benjamin - Autobiography

- Freud, Sigmund — A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis

- Freud, Sigmund - Beyond the Pleasure Principle

- Freud, Sigmund — Delusion and Dream

- Freud, Sigmund - Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis for Beginners

- Freud, Sigmund - Leonardo da Vinci

- Freud, Sigmund - Interpretation of Dreams

- Freud, Sigmund - Moses And Monotheism

- Freud, Sigmund — Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis

- Freud Sigmund — Psychopathology of Everyday Life

- Freud, Sigmund - Reflections on War and Death

- Freud, Sigmund - Selected Papers on Hysteria and Other Psychoneuroses

- Freud, Sigmund - The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement

- Freud, Sigmund — Three Contributions to the Sexual Theory

- Freud, Sigmund — Totem and Taboo

- Freud, Sigmund — Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious

- Frost, Robert - A Boy’s Will

- Frost, Robert — Miscellaneous Poems to 1920

- Frost, Robert — Mountain Interval

- Frost, Robert — North of Boston

- Frost, Robert — “The Road Not Taken

- Gaiman, Neil — “A Study in Emerald”

- Gaiman, Neil - “Bitter Grounds”

- Gaiman, Neil - “Cinnamon”

- Gaiman, Neil - “I Cthulhu”

- Gaiman, Neil - “The Case of the Four and Twenty Blackbirds”

- Gaiman, Neil - “The Day the Saucers Came”

- Gaiman, Neil — The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains

- Garcia Marquez, Gabriel — The Autumn of the Patriarch

- Garcia Marquez, Gabriel — 10 Stories Online

- Gibbon, Edward - The History Of The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire

- Ginsberg, Allen — America

- Ginsberg, Allen — Homework

- Ginsberg, Allen — Howl

- Ginsberg, Allen, — America, Kaddish Part 1, A Supermarket in California, Sunflower Sutra

- Ginsberg, Allen — Taking a Walk through Leaves of Grass

- Goethe — Faust

- Goethe — Faust (Illustrated by Delacroix)

- Goethe — The Sorrows of Young Werther

- Goethe — Theory of Colors (background info)

- Gogol, Nikolai - The Dead Souls

- Gogol, Nikolai - The Nose

- Gogol, Nikolai — Taras Bulba

- Gramsci, Antonio — Selected Writings

- Grimm Brothers - Grimm’s Fairy Tales

- Hammett, Dashiell - Arson Plus

- Harbou, Thea von — Metropolis

- Hardy, Thomas - Collected Stories

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel - The House of the Seven Gables

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel - The Scarlet Letter

- Hegel, GWF — Lectures on the History of Philosophy

- Hegel, GWF — Philosophy of Mind

- Hegel, GWF — Philosophy of Right

- Hegel, GWF — The Phenomenology of the Spirit

- Hemingway, Ernest - The First Forty Nine Stories (includes “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”)

- Hayek, Friedrich - The Use of Knowledge in Society

- Henley - Invictus

- Herodotus — The History of Herodotus V. 1 (Macaulay translation)

- Herodotus, The History of Herodotus V. 2 (Macaulay translation)

- Hesse, Hermann - Siddhartha

- Hobbes, Thomas - Leviathan

- Homer — The Iliad

- Homer — The Odyssey

- Hope, Anthony — The Prisoner of Zenda

- Hughes, Langston and Hurston, Zora Neale - The Mule Bone

- Hugo, Victor - Hunchback of Notre Dame

- Hugo, Victor - Les Miserables

- Hume, David - A Treatise of Human Nature

- Hume, David - Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

- Hume, David - Enquiry into the Principles of Morals

- Hume, David ‑An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

- Hurston, Zora Neale - Poker!

- Hurston, Zora Neale - Three Plays (Lawing and Jawing; Forty Yards; Woofing)

- Huxley, Aldous - Brave New World

- Huxley, Aldous — Crome Yellow

- Huxley, Aldous — Mortal Coils

- Ibsen, Henrik - A Doll’s House

- Ibsen, Henrik — An Enemy of the People

- Ibsen, Henrik - Hedda Gabler

- Ibsen, Henrik - Peer Gynt

- Irving, Washington - The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

- James, Henry - The Ambassadors

- James, Henry — The American

- James, Henry - The Wings of the Dove

- James, Henry - Turn of the Screw

- James, William — Essay in Radical Empiricism

- James, William - Pragmatism

- James, William - Varieties of Religious Experience

- Joyce, James - A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

- Joyce, James - Chamber Music

- Joyce, James - Dubliners

- Joyce, James - Finnegans Wake

- Joyce, James - Ulysses

- Kafka, Franz - “A Hunger Artist”

- Kafka, Franz — “A Country Doctor”

- Kafka, Franz — Amerika (German Edition)

- Kafka, Franz — “A Report to an Academy”

- Kafka, Franz — “Before the Law”

- Kafka, Franz - “In the Penal Colony”

- Kafka, Franz — The Castle/Das Schloß (in German)

- Kafka, Franz — “The Great Wall of China”

- Kafka, Franz - The Metamorphosis

- Kafka, Franz — The Neighbour

- Kafka, Franz - The Trial

- Kant, Immanuel - Critique of Judgement

- Kant, Immanuel - Critique of Practical Reason

- Kant, Immanuel - Critique of Pure Reason

- Kant, Immanuel - Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals

- Kant, Immanuel - Perpetual Peace

- Kant, Immanuel - What is Enlightenment?

- Keats, John - The Poems of John Keats

- Keats, John — Poems, 1817

- Keats, John — Poetical Works

- Kenner, Hugh — Chuck Jones: A Flurry of Drawings

- Keynes, John Maynard - The Economic Consequences of the Peace

- Keynes, John Maynard - The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

- Kierkegaard, Søren - Fear and Trembling

- Kierkegaard, Søren — Philosophical Fragments

- Kierkegaard, Søren - Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing

- Kierkegaard, Søren — The Sickness Unto Death

- Kierkegaard, Søren - Two Discourses on God and Man

- Kipling, Rudyard - Just So Stories for Little Children

- Kipling, Rudyard - Kim

- Kipling, Rudyard - The Jungle Book

- Lao-tzu — The Tao-te Ching

- Lawrence, D.H — Lady Chatterley’s Lover

- Lawrence, D.H. - Sons and Lovers

- Lawrence, D.H. — Women in Love

- Leibniz — Theodicy

- LeRoux, Gaston — Phantom of the Opera

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude - Tristes tropiques

- Lewis, C.S. — Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics

- Lewis, C.S. — The Abolition of Man

- Lewis, Sinclair — Arrowsmith

- Lewis, Sinclair - Babbitt

- Lewis, Sinclair — It Can’t Happen Here

- Locke, John — An Essay on Human Understanding

- Locke, John - Second Treatise on Government

- London, Jack - The Call of the Wild

- London, Jack - White Fang

- Lovecraft, HP - Collected Stories

- Lovecraft, HP — Supernatural Horror in Literature

- Lovecraft, HP — Free Complete, Works of H.P. Lovecraft

- Lucretius - On the Nature of the Things

- Machiavelli, Niccolò - The Prince

- Madison, Hamilton & Jay - The Federalist Papers

- Malthus, Thomas — An Essay on the Principle of Population

- Maimonides — Guide for the Perplexed

- Mann, Thomas — Death in Venice

- Marx and Engels - The Communist Manifesto

- Marx, Karl — The Works of Karl Marx (mostly in German)

- Marx, Karl — Das Kapital

- Marx, Karl - The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir — The Collected Poems of Vladimir Mayakovsky

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir - Whom Should I Be?

- Maupassant, Guy de - Original Short Stories

- McCrae, John — “In Flanders Fields”

- Melville, Herman - Billy Budd

- iPad/iPhone — Text — ZIP — Read Online Now

- Melville, Herman - Moby Dick

- Melville, Herman — Pierre

- Mencken, H.L. — The American Language

- Mencken, H.L. — The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche

- Mill, John Stuart- On Liberty

- Mill, John Stuart - Utilitarianism

- Miller, Henry — The Books in My Life

- Milton, John - Paradise Lost

- Milton, John — Paradise Regained

- Milton, John - The Poetical World

- Minsky, Marvin — The Emotion Machine

- Mirbeau, Octave — La 628-E8 (in French)

- Molière - Collected Works (in French)

- Molière - Le Bourgeois gentilhomme

- Molière - Tartuffe

- Montaigne — Essays

- Montesquieu - The Persian Letters

- Montesquieu - The Spirit of the Laws

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud — Anne of Green Gables

- More, Thomas - Utopia

- Morrison, Toni — “Sweetness”

- Muir, John — My First Summer in the Sierra

- Muir, John — The Mountains of California

- Muir, John — The Yosemite

- Muir, John — Travels in Alaska

- Munro, Alice — Collection of 18 Stories

- Murakami, Haruki — 6 Short Stories

- Murakami, Haruki — “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning”

- Nabokov, Vladimir - “Cloud, Castle, Lake”

- Nabokov, Vladimir — “Signs and Symbols”

- Nabokov, Vladimir — Lectures on Russian Literature

- Nabokov, Vladimir — Lecture on The Metamorphosis

- Nabokov, Vladimir - “The Aurelian”

- Nabokov, Vladimir — “The Art of Translation”

- Newton, Isaac — Opticks

- Newton, Isaac — Principia

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Beyond Good and Evil

- Nietzsche, Friedrich- Ecce Homo

- Nietzsche, Friedrich — Genealogy of Morals

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Homer and Classical Philology

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Human, All Too Human

- Nietzsche, Friedrich — On the Future of our Educational Institutions

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Selected Letters

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - The Anti Christ

- Nietzsche, Friedrich — The Birth of Tragedy

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - The Case Against Wagner

- Nietzsche, Friedrich — The Dawn of Day

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - The Gay Science

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Thus Spake Zarathustra

- Nietzsche, Friedrich - Twilight of the Idols

- Norris, Frank — McTeague

- Northup, Solomon — Twelve Years a Slave

- O’Neill, Eugene - Anna Christie

- O’Neill, Eugene - Beyond the Horizon

- O’Neill, Eugene - The Hairy Ape

- O’Neill, Eugene - The Iceman Cometh

- Oates, Joyce Carol — “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?”

- Orwell, George — 50 Essays

- Orwell, George - 1984

- Orwell, George — A Clergyman’s Daughter

- Orwell, George - Animal Farm

- Orwell, George - Burmese Days

- Orwell, George - Down and Out in Paris and London

- Orwell, George - Homage to Catalonia

- Orwell, George - Politics and the English Language

- Orwell, George — Review of Mein Kampf

- Orwell, George — Review of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Portrait of the Antisemite

- Orwell, George - Looking Back on the Spanish war

- Orwell, George — New Words

- Orwell, George — Rudyard Kipling

- Orwell, George — The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius

- Orwell, George — War Time Diaries (1938–1942)

- Ovid — Metamorphoses

- Paine, Thomas - Common Sense

- Paine, Thomas - Rights of Man

- Paine, Thomas — The Age of Reason

- Pascal, Blaise — The Pensées

- Pascal, Blaise — The Provincial Letters

- Perrault, Charles — Cinderella

- Planck, Max — Eight Lectures on Theoretical Physics

- Plath, Sylvia — A Lesson in Vengeance

- Plath, Sylvia - Ariel

- Plath, Sylvia — Blackberrying

- Plath, Sylvia — Daddy

- Plath, Sylvia — Dream with Clam-Diggers

- Plato — Collected Works

- Plato — Three Illustrated Dialogues by Plato: Euthyphro, Meno, Republic Book I

- Plato - Symposium

- Plato - The Apology, Phaedo, and Crito of Plato

- Plato - The Republic

- Plutarch - Lives

- Poe, Edgar Allan — The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 1

- Poe, Edgar Allan — The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 2

- Poe, Edgar Allan — The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 3

- Poe, Edgar Allan — The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 4

- Poe, Edgar Allan — The Works of Edgar Allan Poe — Volume 5

- Poe, Edgar Allan — Tales of Mystery and Imagination

- Poe, Edgar Allan - The Complete Poetical Works

- Poe, Edgar Allan - The Raven (Illustrated by Gustave Doré)

- Poe, Edgar Allan - The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket

- Popper, Karl — The Logic of Scientific Discovery

- Potter, Beatrix — The Tale of Peter Rabbit

- Pound, Ezra — Canto I

- Pound, Ezra — Canto XVI

- Pound, Ezra - Cathay

- Pound, Ezra — Personae

- Proust, Marcel - Swann’s Way

- Proust, Marcel - Within a Budding Grove

- Proust, Marcel - The Guermantes Way

- Proust, Marcel - Cities on the Plain

- Proust, Marcel - The Captive

- Proust, Marcel - The Sweet Cheat Gone

- Proust, Marcel - Time Regained

- Proust, Marcel — À la recherche du temps perdu

- Pushkin, Alexander — Eugene Onegin

- Rabelais — Gargantua and Pantagruel

- Racine, Jean — Andromaque

- Racine, Jean — Phaedre (English)

- Rand, Ayn - Anthem

- Reed, Lou — O Delmore how I miss you

- Reed, John - The Ten Days That Shook the World

- Richardson, Samuel — Clarissa

- Rilke, Rainer Maria — Duino Elegies

- Roth, Philip — “Epstein”

- Roth, Philip — “The Conversion of the Jews”

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques — Emile

- Rousseau, Jean Jacques — Julie; ou, la Nouvelle Héloïse

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - The Confessions

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - The Social Contract & Discourses

- Rucker, Rudy — Postsingular

- Rucker, Rudy — Turing and Burroughs: A SF Novel

- Rucker, Rudy — The Big Aha

- Rucker, Rudy — The Hollow Earth

- Rucker, Rudy — The Men in the Back Room at the Country Club

- Rucker, Rudy — The Ware Tetralogy (Background)

- Russell, Bertrand — Free Thought and Official Propaganda

- Russell, Bertrand - Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy

- Russell, Bertrand — Mysticism and Logic and Other Essays

- Russell, Bertrand - Political Ideals

- Russell, Bertrand — The Conquest of Happiness

- Russell, Bertrand - The Problems of Philosophy

- Russell, Bertrand - Western Philosophy

- Russell, Bertrand — Why I Am Not a Christian

- Ryle, Gilbert — The Concept of Mind

- Salinger, JD — Slight Rebellion Off Madison

- Santayana, George — Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy: Five Essays

- Santayana, George — The Life of Reason

- Santayana, George — These Sense of Beauty

- Santayana, George — Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante and Goethe

- Sartre, Jean-Paul - Existentialism Is a Humanism

- Sartre, Jean-Paul — Nausea

- Read Online Now (French version)

- Scott, Sir Walter - Ivanhoe

- Schopenhauer, Arthur - The World as Will and Representation

- Schopenhauer, Arthur — The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer; On Human Nature

- iPad/iPhone — Kindle + Other Formats (find German version here)

- Schopenhauer, Arthur — Studies in Pessimism

- Seneca — The Tao of Seneca: Practical Letters from a Stoic Master (3 volumes)

- Seneca - On Benefits

- Sewell, Anna — Black Beauty

- Shackleton, Ernest - South: The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition

- Shakespeare, William — Complete Works in an HTML Edition by the Folger Shakespeare Library

- Shakespeare, William - The Complete Works

- Shakespeare, William - All’s Well Ends Well

- Shakespeare, William — Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare, William — As You Like It

- Shakespeare, William - A Midsummer’s Night Dream

- Shakespeare, William — Coriolanus

- Shakespeare, William — Cymbeline

- Shakespeare, William - Hamlet

- Shakespeare, William — Henry IV (Part 1)

- Shakespeare, William — Henry IV (Part 2)

- Shakespeare, William — Henry V

- Shakespeare, William — Henry VI Part 1

- Shakespeare, William — Henry VI Part 2

- Shakespeare, William — Henry VI Part 3

- Shakespeare, William — Henry VIII

- Shakespeare, William - Julius Caesar

- Shakespeare, William — King John

- Shakespeare, William — King Lear

- Shakespeare, William — Love’s Labor’s Lost

- Shakespeare, William - Macbeth

- Shakespeare, William — Measure for Measure

- Shakespeare, William — Much Ado About Nothing

- Shakespeare, William - Othello

- Shakespeare, William — Pericles

- Shakespeare, William — Richard II

- Shakespeare, William — Richard III

- Shakespeare, William - Romeo & Juliet

- Shakespeare, William — The Comedy of Errors

- Shakespeare, William - The Merchant of Venice

- Shakespeare, William — The Merry Wives of Windsor

- Shakespeare, William - The Taming of the Shrew

- Shakespeare, William — The Tempest

- Shakespeare, William — The Two Noble Kinsmen

- Shakespeare, William — The Winter’s Tale

- Shakespeare, William — Timon of Athens

- Shakespeare, William — Titus Andronicus

- Shakespeare, William — Troilus and Cressida

- Shakespeare, William — Twelfth Night

- Shakespeare, William — Two Gentleman of Verona

- Shaw, George Bernard — Pygmalion

- Shelley, Mary - Frankenstein

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe — Complete Works

- Sinclair, Upton - The Jungle

- Smith, Adam - The Theory of Moral Sentiments

- Smith, Adam - The Wealth of Nations

- Sophocles - Antigone

- Sophocles - Oedipus Trilogy

- Spenser, Edmund - The Faerie Queene

- Spinoza — The Chief Works of Benedict de Spinoza, 2 vols.

- Spinoza — Ethics

- St. Augustine — Confessions

- Stein, Gertrude - Matisse Picasso and Gertrude Stein

- Stein, Gertrude - Tender Buttons

- Stein, Gertrude - Three Lives : stories of the Good Anna, Melanctha and the Gentle Lena

- Stein, Gertrude - The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

- Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de

- Stendhal — The Red and the Black

- French: Kindle + Other Formats

- English: Read Online Now

- Sterne, Laurence — The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

- Stevenson, Robert Louis - Olalla

- Stevenson, Robert Louis - The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

- Stevenson, Robert Louis - Treasure Island

- Stoker, Bram - Dracula

- Stoker, Bram — The Mystery of the Sea

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher - Uncle Tom’s Cabin

- Strunk Jr., William — The Elements of Style

- Suetonius - The Lives of the Twelve Caesars

- Sun Tzu - The Art of War

- Swift, Jonathan - A Tale of the Tub

- Swift, Jonathan - Gulliver’s Travels

- Thackeray, William Makepeace — Vanity Fair

- Thoreau, Henry David - Walden

- Thompson, Hunter S. — Collection of 10 Essays

- Thompson, Hunter S. — Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

- Thucydides — The History of the Peloponnesian War

- Tocqueville, Alexis de - Democracy in America Vol 1.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de - Democracy in America Vol 2.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. — A Middle English Vocabulary

- Tolstoy, Leo — A Letter to a Hindu

- Tolstoy, Leo - Anna Karenina

- Tolstoy, Leo — Fables for Children

- Tolstoy, Leo - Master and Man

- Tolstoy, Leo — The Cossacks

- Tolstoy, Leo — The Death of Ivan Ilych

- Tolstoy, Leo — The Kingdom of God is Within You

- Tolstoy, Leo — The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories

- Tolstoy, Leo - The Pathways of Life (aka Wise Thoughts for Every Day)

- Tolstoy, Leo — Tolstoy on Shakespeare

- Tolstoy, Leo - War and Peace

- Tolstoy, Leo — What is Art?

- Tolstoy, Leo - What Men Live by and Other Tales

- Trollope, Anthony - The Life of Cicero

- Turgenev, Ivan Sergeevich - Fathers and Children

- Twain, Mark — On the Decay of the Art of Lying

- Twain, Mark - The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- Twain, Mark - The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

- Twain, Mark - The $30,000 Bequest

- Twain, Mark — The Prince and the Pauper

- U. Chicago — The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th Edition

- Untermeyer, Louis (editor) — Modern British Poetry

- Vasari, Giorgio — The Lives of the Artists

- Vasari, Giorgio — The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

- Vatsyayana - The Kama Sutra

- Veblen, Thorstein - The Theory of the Leisure Class

- Verne, Jules - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

- Verne, Jules - Around the World in 80 Days

- Verne, Jules - A Journey into the Center of the Earth

- Verne, Jules — The Mysterious Island

- Voltaire - Candide

- Voltaire — Micromégas

- Voltaire — Socrates

- Voltaire — The Philosophical Dictionary

- Voltaire — The Works of Voltaire

- Virgil - The Aeneid

- Vonnegut, Kurt — 2 B R O 2 B

- Vonnegut, Kurt - The Big Trip Up Yonder

- Vonnegut, Kurt - “The Drone”

- Wallace, David Foster - “9/11: The View From the Midwest”

- Wallace, David Foster - “All That”

- Wallace, David Foster - “An Interval”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Asset”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Backbone”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Consider the Lobster”

- Wallace, David Foster - “David Lynch Keeps His Head”

- Wallace, David Foster - “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Everything is Green”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Federer as Religious Experience”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Good People”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Host”

- Wallace, David Foster- “Incarnations of Burned Children”

- Wallace, David Foster - Little Expressionless Animals

- Wallace, David Foster - “Several Birds”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of aluxury cruise”

- Wallace, David Foster - “The String Theory”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Ticket to the Fair”

- Wallace, David Foster - “Wiggle Room”

- Weber, Max — Essays in Sociology

- Weber, Max — The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

- Wells, H.G. — A Short History of the World

- Wells, H.G. — Experiment in Autobiography

- Wells, H.G. — The Invisible Man

- Wells, H.G.- The Island of Dr. Moreau

- Wells, H.G. - The Time Machine

- Wells, H.G. - The War of the Worlds

- Wells, H.G. — Twelve Stories and a Dream

- Wharton, Edith - The Age of Innocence

- Whitman, Walt — Complete Prose Works

- Whitman, Walt - Leaves of Grass

- Whitman, Walt — Song of Myself

- Wilde, Oscar - Picture of Dorian Gray

- Wilde, Oscar — The Happy Prince and Other Stories

- Wilde, Oscar - The Importance of Being Earnest

- Wilde, Oscar — The Complete Works

- Wilde, Oscar — Collected Poems

- William, Margery — The Velveteen Rabbit

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig — The Brown Book

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig - Notebooks, 1914–1916

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig — Notes on Logic

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig — Philosophical Investigations (German)

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig - Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig - Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (German-English Side by Side Edition)

- Wollstonecraft, Mary — A Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Woolf, Virginia - A Room of One’s Own

- Woolf, Virginia - Mrs Dalloway

- Woolf, Virginia - To the Lighthouse

- Woolf, Virginia - The Voyage Out

- Wordsworth, William - Lyrical Ballads, with other poems

- Wright, Frank Lloyd — The Disappearing City

- Yeats, William Butler - Collected Poems

- Zamyatin, Eugene — We

- Zola, Émile - Germinal

- Zola, Émile - Therese Raquin

- Zweig, Stefan — Conqueror of the Seas — The Story of Magellan

- Zweig, Stefan — Paul Verlaine

- Zweig, Stefan — Romain Rolland: The Man and His Work

- Zweig, Stefan — The Burning Secret

Religious Texts

- Bhagavad Gita

- The King James Edition of the Bible

- The Qur’an (Translated by Abdullah Yusuf Ali)

- Epub — Kindle (Mobi) — PDF — Read Online Now

- Vedas

Assorted Texts

- 700 Free eBooks Made Available by the University of California Press - Overview

- 243 Free eBooks on Design, Data, Software, Web Development & Business from O’Reilly Media - Overview

- 48 Free eBooks from Cambridge University - Read Online Now

- 250 Free Art Books From the Getty Museum - Overview

- 397 Free Art Catalogs from The Metropolitan Museum of Art — Overview

- 99 Modern Art Books by the Guggenheim - Read Online Now

- Assorted NASA eBooks — Web Site

- Assortment of Classic Books for Kids — Read Online Now

- Chicago Manual of Style — Read Online Now

- Classic Texts in the History of Psychology — Read Online Now

- Hanover Historical Texts Collection — Read Online Now

- Smithsonian Online Collection — Read Online Now

- The History of Cartography (3 Volumes) — Read Online Now

- The International Children’s Digital Library Offers Free eBooks for Kids in Over 40 Languages — Overview

- Baldwin, Frederick - Dear Monsieur Picasso — PDF

- boyd, dana — It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens — PDF

- Boyle, James — The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind — PDF — HTML — ePub

- Chomsky, Noam — Year 501: The Conquest Continues — Read Online Now

- Chomsky, Noam - Secrets, Lies and Democracy — Read Online Now

- Brand, Stewart — The Whole Earth Catalog — Read Online Now

- Doctorow, Cory - I, Robot — Kindle + Other Formats

- Doctorow, Cory — With a Little Help — Kindle + Other Formats

- Free Art Catalogs from The Metropolitan Museum of Art — Read Online Now

- Carroll, Jean - Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson — PDF — RTF

- Kamenetz, Anya — The Edupunks’ Guide to a DIY Credential — Kindle + Other Formats

- Lessig, Lawrence - The Future of Ideas — PDF

- Lethem, Jonathan — The Empty Room — Read Online Now

- Scroggy, David — The Blade Runner Sketchbook: The Art of Syd Mead and Ridley Scott — Read Online Now

- Vakoch, Douglas (ed) — Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication

- Various Authors — Out of Copyright Science Fiction for the Kindle

- Wright, Erik Olin — Selected Writings — Read Online Now

This list of Free eBooks has received mentions in the The Daily Beast, Computer World, Gizmodo and Lifehacker.

Read More...Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov Strikingly Illustrated by Expressionist Painter Alice Neel (1938)

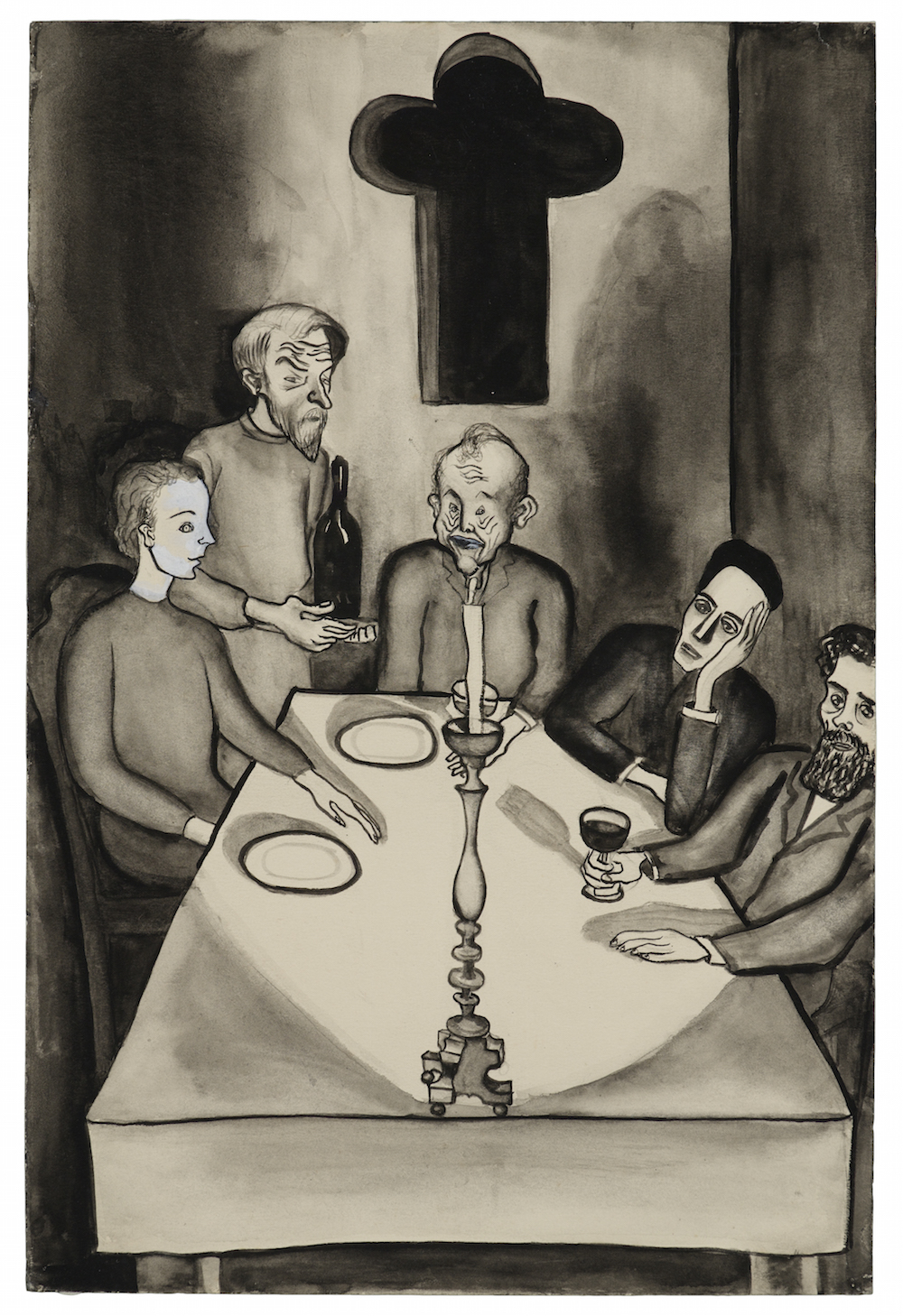

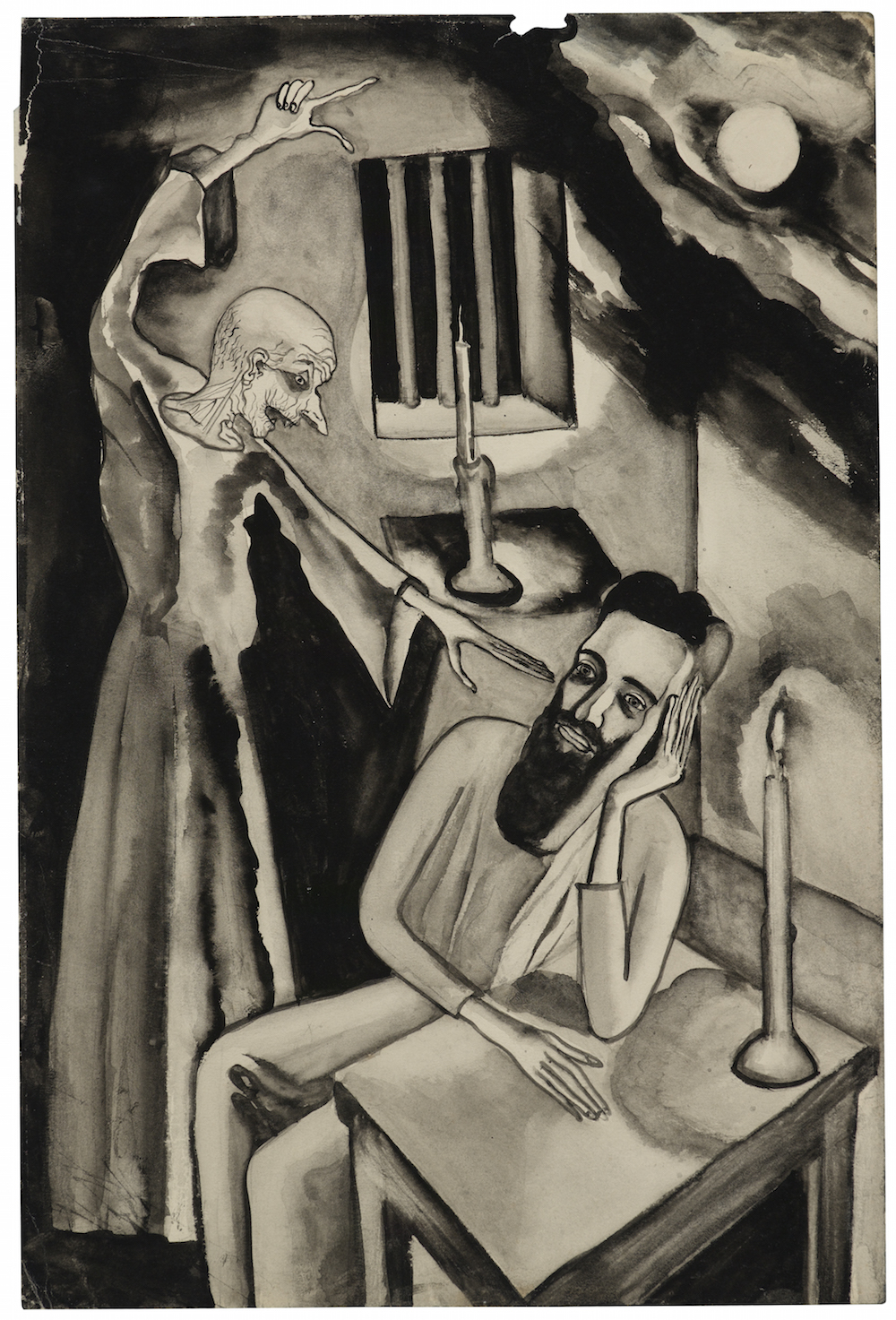

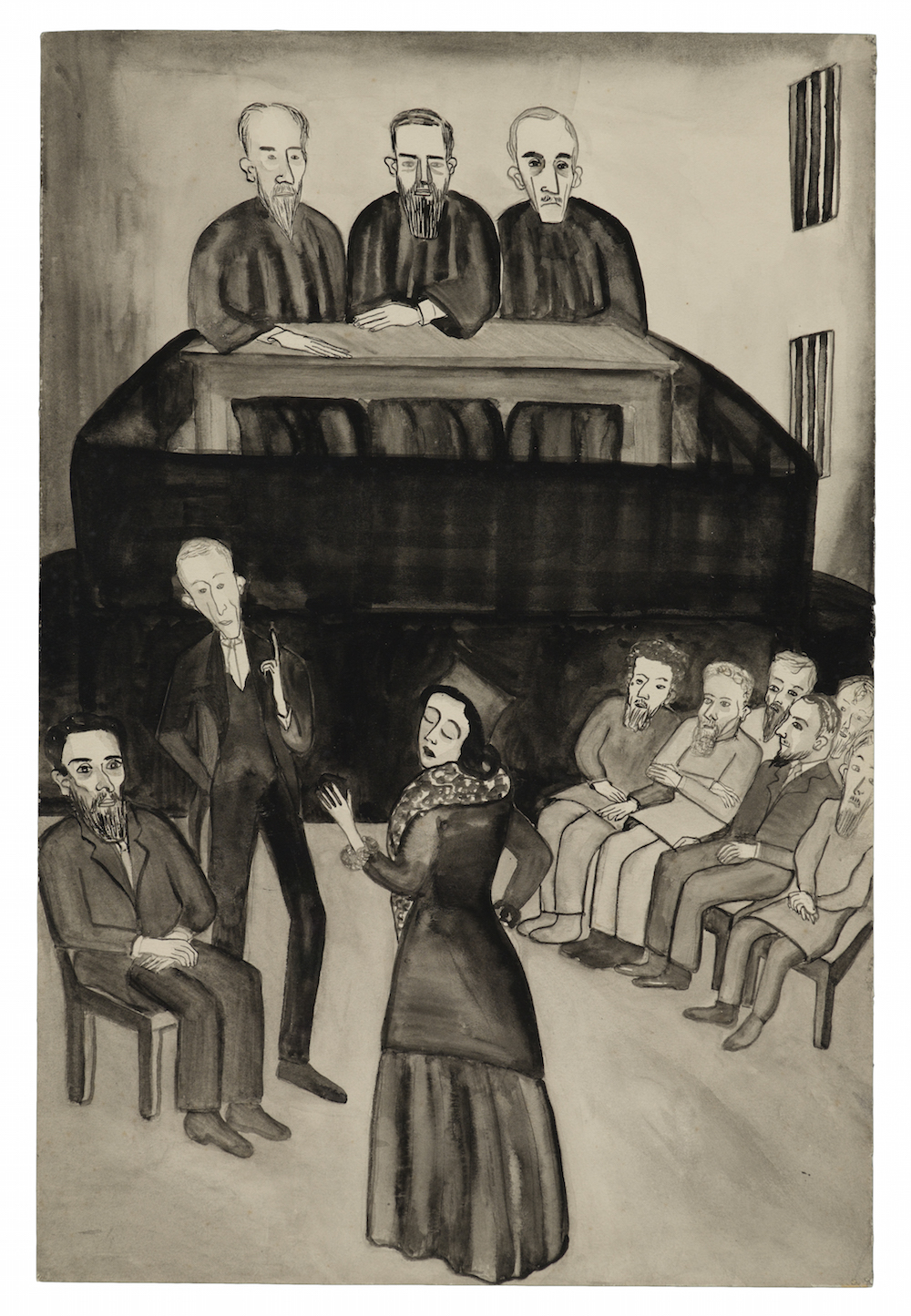

Images belong to The Estate of Alice Neel.

We all know the reputation of 19th-century Russian novels: long, dense bricks of pure prose, freighted with deep moral concerns and, to the uninitiated, enlivened only by a confusing farrago of patronymics. And sure, while they may have a bit of a learning curve to them, these classic works of literature also, so their advocates assure us, boast plenty to keep them relevant today — just the quality, of course, that makes them classic works of literature in the first place.

While we should by all means read them, that doesn’t mean we can’t get a taste of these much-discussed books before we heft them and turn to page one by, for example, checking out their illustrations. These vary in quality with the editions, of course, but how much of the art that has ever accompanied, say, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov has looked quite as evocative as the never-published illustrations here? They come from the hand of the Pennsylvania-born artist Alice Neel, commissioned in the 1930s for an edition of the novel that never saw the printing press.

The Paris Review’s Dan Piepenberg, posting eight of Neel’s illustrations, highlights “how attuned these two sensibilities are: it’s the marriage of one kind of darkness to another”; “the black storm cloud of Neel’s pen is well suited to Dostoyevsky’s questions of God, reason, and doubt.” And yet Neel also manages to express the novel’s “madness and comedy,” bringing “a manic bathos to these scenes that lends them both gravity and levity; in every wide, glassy pair of eyes, grave questions of moral certitude are undercut by the absurd.”

You can see all of eight of Neel’s Karamazov illustrations at The Paris Review, not that they provide a substitute for reading the novel itself (which you can find in our collection of Free eBooks). After all, that’s the only way to find out what exactly happens at that bacchanal just above.

Related Content:

Fyodor Dostoevsky Draws Elaborate Doodles In His Manuscripts

Albert Camus Talks About Adapting Dostoyevsky for the Theatre, 1959

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...