Morning, friend! Ready to kick off your week with a Beckettian nightmare vision?

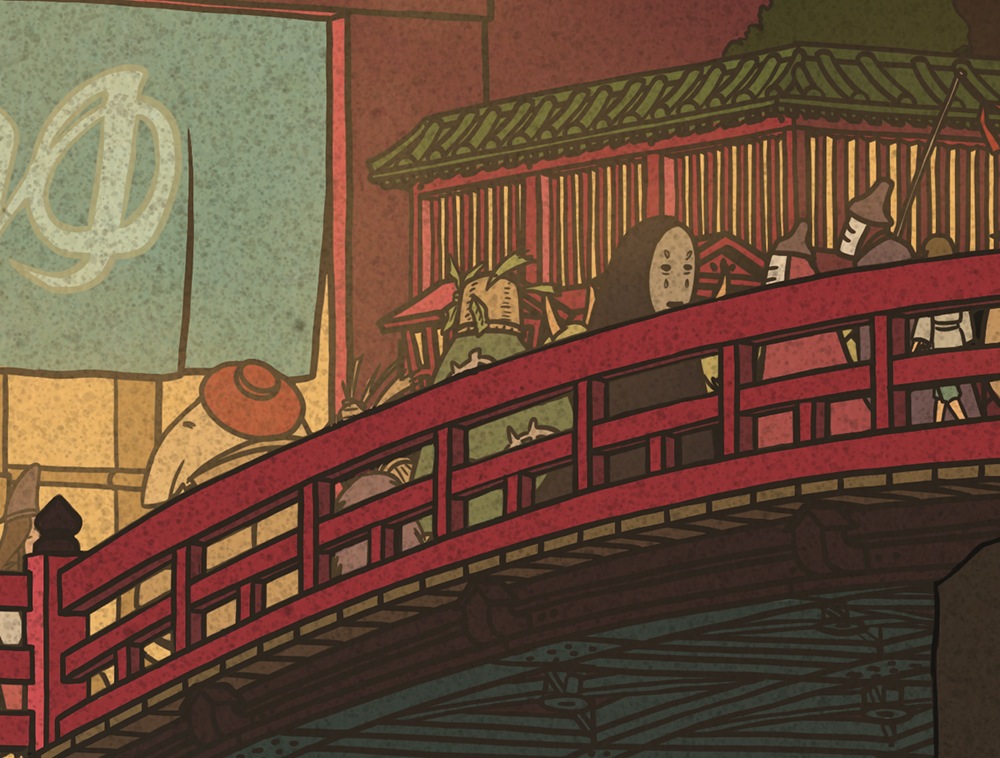

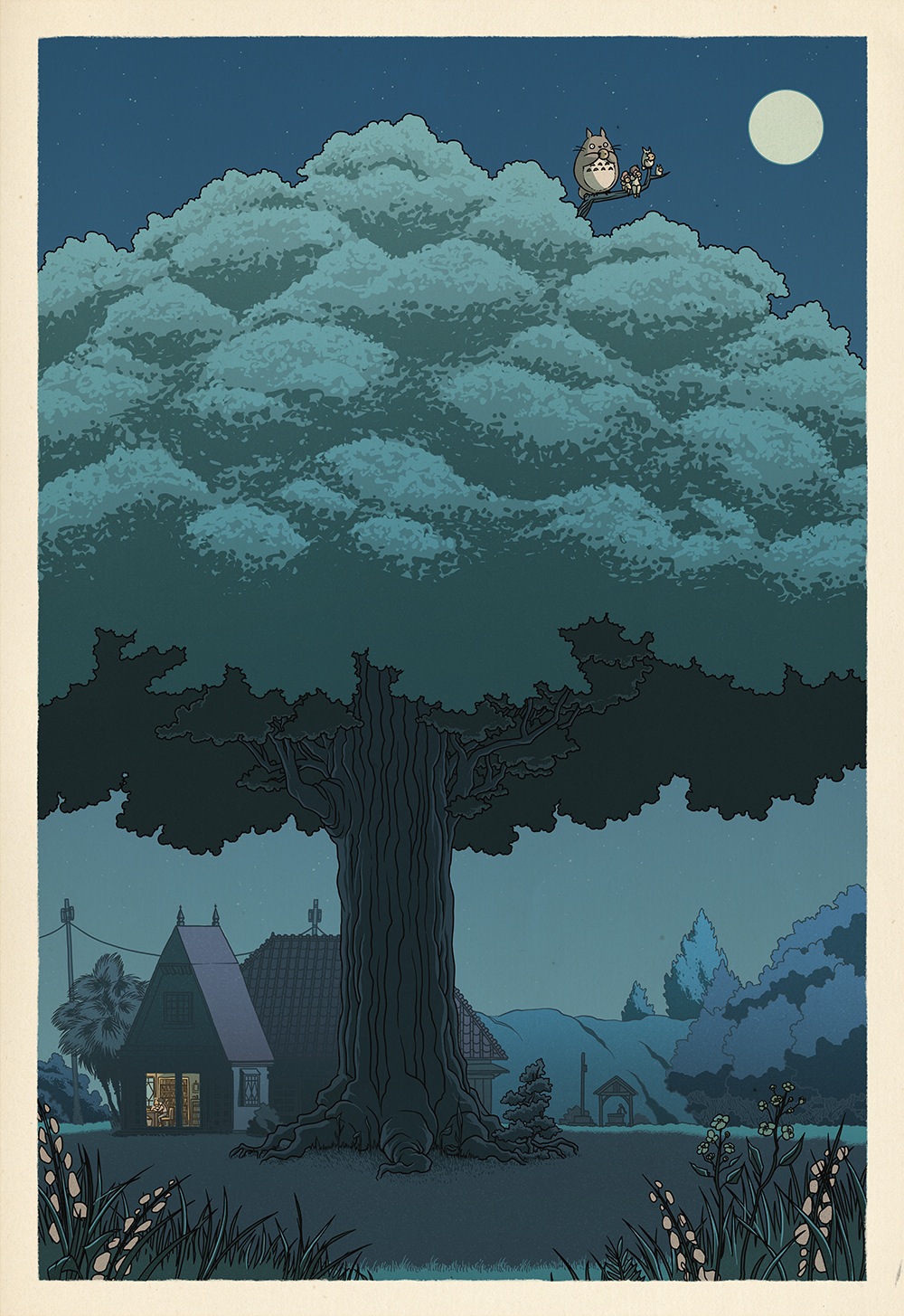

Samuel Beckett scholar Jenny Triggs was earning a masters in Visual Communications at the Edinburgh College of Art when she created the unsettling, cut out animation for his 1953 novel, The Unnamable, above. (Her PhD exhibition, a decade later, was a multi-screen video response to Beckett’s short story, Ping.)

The wretched creatures haunting the film conjure Bosch and Gilliam, in addition to Ireland’s best known avant-garde playwright.

Triggs seem to have drawn inspiration from the nameless narrator’s physical self-assessment:

I of whom I know nothing, I know my eyes are open because of the tears that pour from them unceasingly. I know I am seated, my hands on my knees, because of the pressure against my rump, against the soles of my feet? I don’t know. My spine is not supported. I mention these details to make sure I am not lying on my back, my legs raised and bent, my eyes closed.

Despite the narrator’s effort to keep track of his parts, Triggs ensures that something will always be missing. Her characters make do with rods, bits of chess pieces or nothing at all in places where limbs should be.

Are these birth defects or some sort of wartime disability that precludes prosthetics?

One character is described as “nothing but a shapeless heap… with a wild equine eye.”

The narrator steels himself “to invent another fairy tale with heads, trunks, arms, legs and all that follows.” Meanwhile, he’s tormented by a spiritual push-me-pull-you that feels very like the one afflicting Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot:

Where I am, I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.

Triggs describes The Unnamable as a book that begs to be read aloud, and her narrators Louise Milne and Chris Noon are deserving of praise for parsing the meandering text in such a way that it makes sense, at least atmospherically.

To go on means going from here, means finding me, losing me, vanishing and beginning again, a stranger first, then little by little the same as always, in another place, where I shall say I have always been, of which I shall know nothing, being incapable of seeing, moving, thinking, speaking, but of which little by little, in spite of these handicaps, I shall begin to know something, just enough for it to turn out to be the same place as always, the same which seems made for me and does not want me, which I seem to want and do not want, take your choice, which spews me out or swallows me up, I’ll never know, which is perhaps merely the inside of my distant skull where once I wandered, now am fixed, lost for tininess, or straining against the walls, with my head, my hands, my feet, my back, and ever murmuring my old stories, my old story, as if it were the first time.

Related Content:

Rare Audio: Samuel Beckett Reads From His Novel Watt

Take a “Breath” and Watch Samuel Beckett’s One-Minute Play

Hear Samuel Beckett’s Avant-Garde Radio Plays: All That Fall, Embers, and More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday