20 Free Business MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) That Will Advance Your Career

Art, philosophy, literature and history–that’s mainly what we discuss around here. We’re about enriching the mind. But we’re not opposed to helping you enrich yourself in a more literal way too.

Recently, Business Insider Italy asked us to review our longer list of 1600 MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) and create a short list of 20 courses that can help you advance your career. And, with the help of Coursera and edX, the two top MOOC providers, we whittled things down to the following list.

Above, you’ll find the introductory video for Design Thinking for Innovation, a course from the University of Virginia. Other courses come from such top institutions as Yale, MIT, the University of Michigan and Columbia University. Topics include everything from business fundamentals, to negotiation and decision making, to corporate finance, strategy, marketing and accounting.

One tip to keep in mind. If you want to take a course for free, select the “Full Course, No Certificate” or “Audit” option when you enroll. If you would like an official certificate documenting that you have successfully completed the course, you will need to pay a fee. Here’s the list:

- Business Foundations — University of British Columbia

- Influencing People — University of Michigan

- Introduction to Negotiation: A Strategic Playbook for Becoming a Principled and Persuasive Negotiator — Yale University

- Selling Ideas: How to Influence Others, and Get Your Message to Catch On — University of Pennsylvania/Wharton Business School

-

Effective Problem Solving and Decision Making — University of California-Irvine

- Design Thinking for Innovation — University of Virginia

- Project Management: The Basics for Success — University of California-Irvine

- Work Smarter, Not Harder: Time Management for Personal & Professional Productivity — University of California-Irvine

- Becoming an Entrepreneur — MIT

- Competitive Strategy — Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU)

-

Financial Markets — Yale University (taught by Nobel Prize Winning Economist Robert Shiller)

-

Finance for Non-Financial Professionals — University of California-Irvine

-

Introduction to Corporate Finance — University of Pennsylvania/Wharton Business School

-

Introduction to Financial Accounting — University of Pennsylvania/Wharton Business School

-

Introduction to Marketing — University of Pennsylvania/Wharton Business School

- Managing the Value of Customer Relationships — University of Pennsylvania/Wharton Business School

- Marketing in a Digital World — University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Analytics in Python — Columbia University

- Introduction to User Experience — University of Michigan

- Data Science Essentials — MIT & Microsoft

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Read More...Hear Classic Readings of Poe’s “The Raven” by Vincent Price, James Earl Jones, Christopher Walken, Neil Gaiman, Stan Lee & More

It can seem that the writing of literature and the theory of literature occupy separate great houses, Game of Thrones-style, or even separate countries held apart by a great sea. Perhaps they war with each other, perhaps they studiously ignore each other or obliquely interact at tournaments with acronymic names like MLA and AWP. Like Thomas Pynchon’s characterization of the political right and left, scholars and writers represent opposing poles, the hothouse and the street. That rare beast, the academic poet, can seem like something of a unicorn, or dragon.

…Or like the ominous talking raven in Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous of poems.

The divide between theory and practice is a recent development, a product of state budgeting, political brinksmanship, the relentless publishing mills of academia that force scholars to find a pigeonhole and stay there.… In days past, poets and scholar/theorists frequently occupied the same place at the same time—Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Shelley, and, of course, Poe, whose perennially popular “The Raven” serves as a point-by-point illustration for his theory of composition just as thoroughly as Eliot’s great works bear out his notion of the “objective correlative.”

Poe’s object, the titular creature, is an “archetypal symbol,” writes Dana Gioia, in a poem that aims for what its author calls a “unity of effect.” In his 1846 essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe the poet/theorist tells us in great detail how “The Raven” satisfies all of his other criteria for literature as well, such as achieving its intent in a single sitting, using a repeated refrain, and so on.

Should we have any doubt about how much Poe wanted us to see the poem as the deliberate outcome of a conceptual scheme, we find him three years later, in 1849, the year of his death, delivering a lecture on the “Poetic Principle,” and concluding with a reading of “The Raven.”

John Moncure Daniel of the Richmond Semi-Weekly Examiner remarked after attending one of these talks that “the attention of many in this city is now directed to this singular performance.” At that point, Poe, who hardly made a dime from “The Raven,” had to suffer the indignity of having all of his work go out of print during his brief, unhappy lifetime. Moncure and the Examiner thereby furnished readers “with the only correct copy ever published,” previous appearances, it seems, having contained punctuation errors.

Nonetheless, for all of Poe’s pedantry and penury, “The Raven“ ‘s first appearances made him semi-famous. His readings were a sensation, and it’s a sure bet that his audiences came to hear him read the poem, not deliver a lecture on its principles. Oh, for some proto-Edison in the room with an early recording device. What would it be like to hear the mournful, grief-stricken, alcoholic genius—master of the macabre and inventor of the detective story—intone the raven’s enigmatic “Nevermore”?

While Poe’s speaking voice has receded irretrievably into history, his poetic voice may live close to forever. So mesmerizing are his meter and diction that many great actors known especially for their voices have become possessed by “The Raven.”

Likely when we think of the poem, what first comes to the mind’s ear is the voice of Vincent Price, or James Earl Jones, Christopher Lee, or Christopher Walken, all of whom have given “The Raven” its due.

And so have many other notables, such as the great Stan Lee, Poe successor Neil Gaiman, original Gomez Addams actor John Astin, and venerable Beat poet/scholar Anne Waldman (listen here). You will find those recitations here at this round-up of notable “Raven” readings, and if this somehow doesn’t satiate you, then check out Lou Reed’s take on the poem, the Grateful Dead’s musical tribute, “Raven Space,” or a reading in 100 different celebrity impressions.

Finally, we would be remiss not to mention The Simpsons’ James Earl Jones-narrated parody, a worthy teaching tool for distracted young visual learners. Is it a shame that we now think of “The Raven” as a Halloween yarn fit for the Treehouse of Horror or any number of enjoyable exercises in spooky oratory—rather than the theoretical thought experiment its author seemed to intend? Does Poe rotisserie in his grave as Homer snores in a wingback chair? Probably. But as the author told us himself at length, the poem works! It still never fails to excite our morbid curiosity, enchant our gothic sensibility, and maybe send a chill or two down the spine. Maybe we never really needed Poe to explain it to us.

You can find other literary readings in our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

When Charles Dickens & Edgar Allan Poe Met, and Dickens’ Pet Raven Inspired Poe’s Poem “The Raven”

7 Tips from Edgar Allan Poe on How to Write Vivid Stories and Poems

Download The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe on His Birthday

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch Werner Herzog’s Very First Film, Herakles, Made When He Was Only 19-Years-Old (1962)

Rebellious dwarfs, crazed conquistadors, delusional tycoons, wood-carving ski jumpers: Werner Herzog scholars who attempt to find a pattern in the filmmaker’s choices of subject matter are virtually guaranteed an interesting search, if an ultimately futile one. But they must all start in the same place: Herzog’s very first film Herakles, which mashes up the spectacles of body building, auto racing, and destruction. It does all that in nine minutes to a soundtrack of saxophone jazz, and with frequent references to the titular hero of myth, whom you may know better by his Roman name of Hercules.

“Would he clean the Augean stables?” ask Herakles’ subtitles over footage of one young German man showing off his well-shaped torso. “Would he dispose of the Lernaean Hydra?” they ask of another as he strikes a pose.

Between clips of these bodybuilders performing their labors and questions about whether they could perform those of Hercules, we see militaristic marches, falling bombs, heaps of rubble, and a 1955 racecar crash at Le Mans that killed 83 people. All this juxtaposition tempts us to ask what message the nineteen-year-old Herzog wanted to deliver, but, as in all his subsequent work, he surely wanted less to make an articulable point than to explore the possibilities of cinema itself.

More recently, in Paul Cronin’s interview book Herzog on Herzog, the filmmaker looks back on “my first blunder, Herakles” and finds it “rather stupid and pointless, though at the time it was an important test for me. It taught me about editing together very diverse material that would not normally sit comfortably as a whole,” and in a sense prepared him for an entire cinematic career of very diverse material that would not normally sit comfortably as a whole. “For me it was fascinating to edit material together that had such separate and individual lives. The film was some kind of an apprenticeship for me. I just felt it would be better to make a film than go to film school” — of the non-rogue variety, anyway.

Related Content:

Werner Herzog Teaches His First Online Course on Filmmaking

Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School: Apply & Learn the Art of Guerilla Filmmaking & Lock-Picking

Portrait Werner Herzog: The Director’s Autobiographical Short Film from 1986

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Trigonometry Discovered on a 3700-Year-Old Ancient Babylonian Tablet

One presumption of television shows like Ancient Aliens and books like Chariots of the Gods is that ancient people—particularly non-western people—couldn’t possibly have constructed the elaborate infrastructure and monumental architecture and statuary they did without the help of extra-terrestrials. The idea is intriguing, giving us the hugely ambitious sci-fi fantasies woven into Ridley Scott’s revived Alien franchise. It is also insulting in its level of disbelief about the capabilities of ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, South Americans, South Sea Islanders, etc.

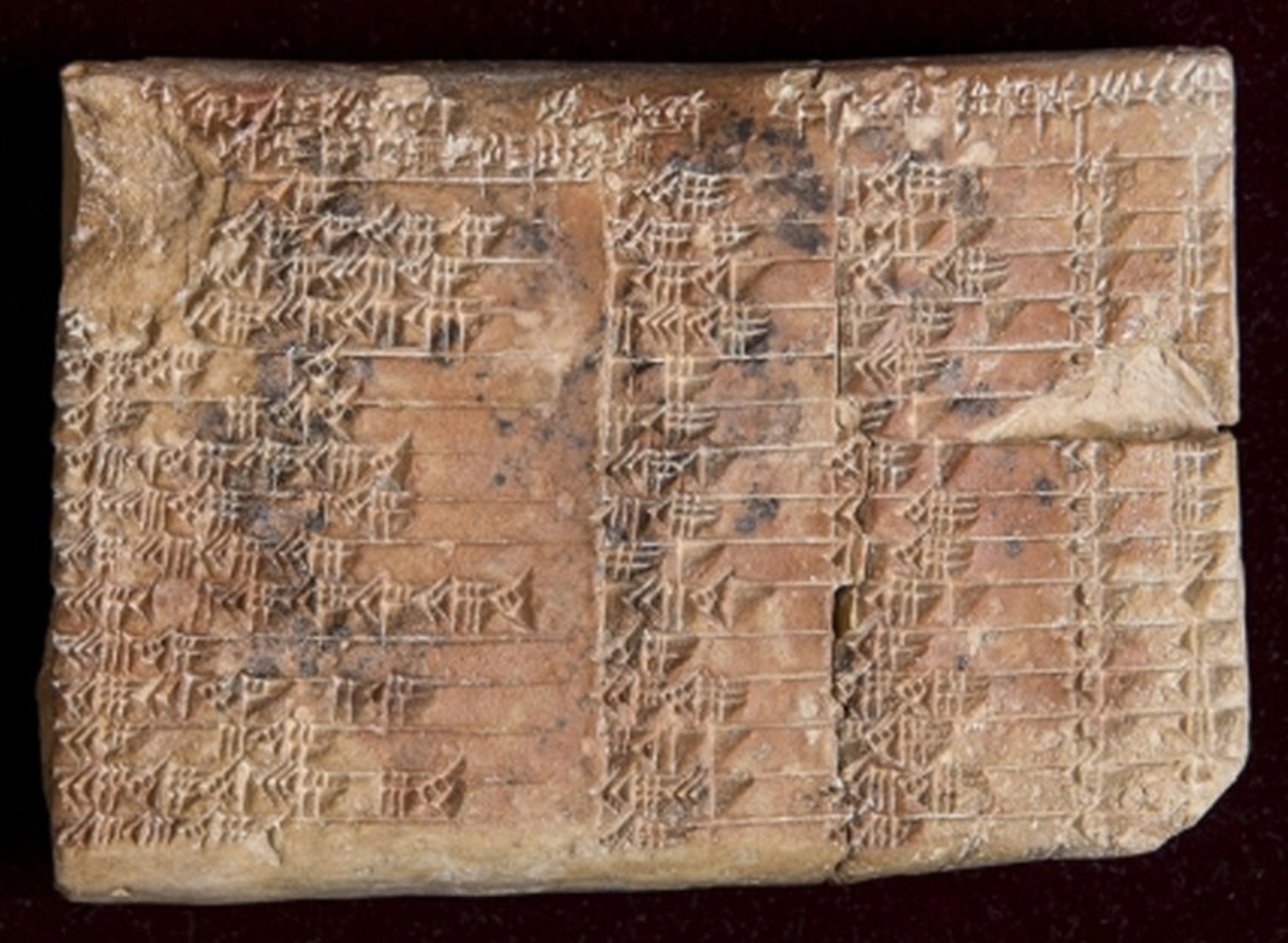

We assume the Greeks perfected geometry, for example, and refer to the Pythagorean theorem, although this principle was probably well-known to ancient Indians. Since at least the 1940s, mathematicians have also known that the “Pythagorean triples”—integer solutions to the theorem—appeared 1000 years before Pythagoras on a Babylonian tablet called Plimpton 322. Dating back to sometime between 1822 and 1762 B.C. and discovered in southern Iraq in the early 1900s, the tablet has recently been re-examined by mathematicians Daniel Mansfield and Norman Wildberger of Australia’s University of New South Wales and found to contain even more ancient mathematical wisdom, “a trigonometric table, which is 3,000 years ahead of its time.”

In a paper published in Historia Mathematica the two conclude that Plimpton 322’s Babylonian creators detailed a “novel kind of trigonometry,” 1000 years before Pythagoras and Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who has typically received credit for trigonometry’s discovery. In the video above, Mansfield introduces the unique properties of this “scientific marvel of the ancient world,” an enigma that has “puzzled mathematicians,” he writes in his article, “for more than 70 years.” Mansfield is confident that his research will fundamentally change the way we understand scientific history. He may be overly optimistic about the cultural forces that shape historical narratives, and he is not without his scholarly critics either.

Eleanor Robson, an expert on Mesopotamia at University College London has not published a formal critique, but she did take to Twitter to register her dissent, writing, “for any historical document, you need to be able to read the language & know the historical context to make sense of it. Maths is no exception.” The trigonometry hypothesis, she writes in a follow-up tweet, is “tediously wrong.” Mansfield and Wildberger may not be experts in ancient Mesopotamian language and culture, it’s true, but Robson is also not a mathematician. “The strongest argument” in the Australian researchers’ favor, writes Kenneth Chang at The New York Times, is that “the table works for trigonomic calculations.” As Mansfield says, “you don’t make a trigonomic table by accident.”

Plimpton 322 uses ratios rather than angles and circles. “But when you arrange it such a way so that you can use any known ratio of a triangle to find the other side of a triangle,” says Mansfield, “then it becomes trigonometry. That’s what we can use this fragment for.” As for what the ancient Babylonians used it for, we can only speculate. Robson and others have proposed that the tablet was a teaching guide. Mansfield believes “Plimpton 322 was a powerful tool that could have been used for surveying fields or making architectural calculations to build palaces, temples or step pyramids.”

Whatever its ancient use, Mansfield thinks the tablet “has great relevance for our modern world… practical applications in surveying, computer graphics and education.” Given the possibilities, Plimpton 322 might serve as “a rare example of the ancient world teaching us something new,” should we choose to learn it. That knowledge probably did not originate in outer space.

Related Content:

How the Ancient Greeks Shaped Modern Mathematics: A Short, Animated Introduction

Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in the Original Akkadian and Enjoy the Sounds of Mesopotamia

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...What Is Freedom? Watch Four Philosophy Animations on Freedom & Free Will Narrated by Harry Shearer

Growing up in America, I heard nearly every behavior, no matter how unpleasant, justified with the same phrase: “It’s a free country.” In her recent book Notes on a Foreign Country, the Istanbul-based American reporter Suzy Hansen remembers singing “God Bless the USA” on the school bus during the first Iraq war: “And I’m proud to be an American / Where at least I know I’m free.” That “at least,” she adds, is funny: “We were free – at the very least we were that. Everyone else was a chump, because they didn’t even have that obvious thing. Whatever it meant, it was the thing that we had, and no one else did. It was our God-given gift, our superpower.”

But how many of us can explain what freedom is? These videos from BBC Radio 4 and the Open University’s animated History of Ideas series approach that question from four different angles. “Freedom is good, but security is better,” says narrator Harry Shearer, summing up the view of seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who imagined life without government, laws, or society as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” The solution, he proposed, came in the form of a social contract “to put a strong leader, a sovereign or perhaps a government, over them to keep the peace” — an escape from “the war of all against all.”

But that escape comes hand in hand with the unpalatable prospect of living under “a frighteningly powerful state.” The nineteenth-century philosopher John Stuart Mill, who wrote a great deal about the state’s proper limitations, based his concept of freedom in something called the “harm principle,” which holds that “the state, my neighbors, and everyone else should let me get on with my life, as long as I don’t harm anyone in the process.” As “the seedbed of genius” and “the basis of enduring happiness for ordinary people,” this individual freedom needs protection, especially when it comes to speech: “Merely causing offense, he thinks, is no grounds for intervention, because, in his view, that is not a harm.”

That proposition remains debated more heatedly now, in the 21st century, than Mill probably could have imagined. But then as now, and as in any time of human history, we live in more or less the same world, “a world festering with moral evil, a world of wars, torture, rape, murder, and other acts of meaningless violence,” not to mention “natural evil” like disease, famine, floods, and earthquakes. This gives rise to perhaps the oldest problem in the philosophical book, the problem of evil: “How could a good god allow anyone to do such horrific things?” Some have taken the fact that the wars, murders, floods, and earthquakes continue as evidence that no such god exists.

But had that god created “human beings that always did the right thing, never harmed anyone else, never went astray,” we’d all have ended up “automata, preprogrammed robots.” Better, in this view, “to have free will with the genuine risk that some people will end up evil than to live in a world without choice.” Even so, the mere mention of free will, a concept no more easily defined than that of freedom itself, opens up a whole other can of worms, especially in light of research like neuroscientist Benjamin Libet’s.

Libet, who “wired up subjects to an EEG machine, measuring brain activity via electrodes on our scalps,” found that brain activity initiating a movement actually happened before the subjects thought they’d decided to make that movement. Does that disprove free will? Does evil disprove the existence of a good god? Does offense cause the same kind of harm as physical violence? Should we give up more security for freedom, or more freedom for security? These questions remain unanswered, and quite possibly unanswerable, but that doesn’t make considering the very nature of freedom any less necessary as human societies — those in “free countries” and otherwise — find their way forward.

Related Content:

47 Animated Videos Explain the History of Ideas: From Aristotle to Sartre

An Animated Aldous Huxley Identifies the Dystopian Threats to Our Freedom (1958)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Earliest Known Appearance of the F‑Word, in a Bizarre Court Record Entry from 1310

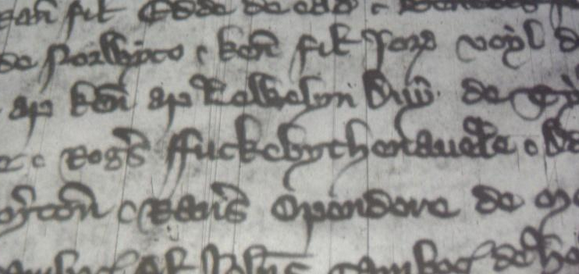

Photo by Paul Booth

You value decorum, propriety, eloquence, you treasure le mot juste and agonize over diction as you compose polite but strongly-worded letters to the editor. But alas, my literate friend, you have the misfortune of living in the age of Twitter, Tumblr, et al., where the favored means of communication consists of readymade mimetic words and phrases, photos, videos, and animated gifs. World leaders trade insults like 5th graders—some of them do not know how to spell. Respected scientists and journalists debate anonymous strangers with cartoon avatars and work-unsafe pseudonyms. Some of them are robots.

What to do?

Embrace it. Insert well-placed profanities into your communiqués. Indulge in bawdiness and ribaldry. You may notice that you are doing no more than writers have done for centuries, from Rabelais to Shakespeare to Voltaire. Profanity has evolved right alongside, not apart from, literary history. T.S. Eliot, for example, knew how to go lowbrow with the best of them, and gets credit for the first recorded use of the word “bullshit.” As for another, even more frequently used epithet in 24-hour online commentary?—well, the word “F*ck” has a far longer history, granting its apt public use recently by seismologist Steven Gibbons an added authority.

Not long ago we alerted you to the first known use of the versatile obscenity in a 1528 marginal note scribbled in Cicero’s De Officiis by a monk cursing his abbot. Not long after this discovery, notes Medievalists.net, another scholar found the word in a 1475 poem called Flen flyys. This was thought to be the earliest appearance of “f*ck” as a purely sexual reference until medieval historian Paul Booth of Keele University discovered an instance dating over a hundred years earlier. Rather than within, or next to, a work of literature, however, the word appears in a set of 1310 English court records. And no, it is decidedly not a legal term.

The documents concern the case of “a man named Roger Fuckebythenavele.” Used three times in the record, the name, says Booth, is probably not a joke made by the scribe but some kind of bizarre nickname, though one hopes not a description of the crime. “Either it refers to an inexperienced copulator, referring to someone trying to have sex with a navel,” says Booth, stating the obvious, “or it’s a rather extravagant explanation for a dimwit, someone so stupid they think that this is the way to have sex.” Our medieval gent had other problems as well. He was called to court three times within a year before being pronounced “outlawed,” which The Independent’s Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith suggests execution but probably refers to banishment.

For the word to have such casually hilarious or insulting currency in the early 14th century, it must have come from an even earlier time. Indeed, “f*ck is a word of German origin,” notes Jesse Sheidlower, author of an etymological history called The F Word, “related to words in several other Germanic languages, such as Dutch, German, and Swedish, that have sexual meanings as well as meaning such as ‘to strike’ or ‘to move back and forth’” (naturally). So, in other words, it’s just a word. But in this case it might have also been a weapon, Booth speculates, wielded “by a revengeful former girlfriend. Fourteenth-century revenge porn perhaps…” If that’s not evidence for you that the present may not be unlike the past, then maybe take note of the appearance of the word “twerk” in 1820.

Related Content:

Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW)

Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The 100 Funniest Films of All Time, According to 253 Film Critics from 52 Countries

Does comedy come with an expiration date? Scholars of the field both amateur and professional have long debated the question, but only one aspect of the answer has become clear: the best comedy films certainly don’t. That notion manifests in the variety of cinematic eras represented in BBC Culture’s recent poll of 177 film critics to determine the 100 greatest comedy films of all time. Most of us have seen Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day at some point (and probably at more than one point) over the past 24 years; fewer of us have seen the Marx Brothers’ picture Duck Soup, but even those of us who consider ourselves far too cool and modern to watch the Marx Brothers have to acknowledge its genius.

That top ten runs as follows:

- Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959)

- Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

- Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

- Groundhog Day (Harold Ramis, 1993)

- Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933)

- Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979)

- Airplane! (Jim Abrahams, David Zucker and Jerry Zucker, 1980)

- Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

- This Is Spinal Tap (Rob Reiner, 1984)

- The General (Clyde Bruckman and Buster Keaton, 1926)

The BBC have published the top 100 results (the last spot being a tie between the late Jerry Lewis’ The Ladies Man and Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy) on their site, accompanied by a full list of participating critics and their votes, critics’ comments on the top 25, an essay on whether men and women find different films funny (mostly not, but with certain notable splits on movies like Clueless and Animal House), another on whether comedy differs from region to region, and another on why Some Like It Hot is number one.

Though no enthusiast of classic Hollywood would ever deny Billy Wilder’s gender-bending 1959 farce any honor, it wouldn’t have come out on top in a poll of American and Canadian critics alone: Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove wins that scenario handily. “Intriguingly, Eastern European critics were much more likely to vote for Dr Strangelove than Western European critics,” adds Christian Blauvelt. “Perhaps the US and countries that used to be behind the Iron Curtain appreciate Dr. Strangelove so much because it ruthlessly satirises the delusions of grandeur held by both sides. And perhaps Some Like It Hot is embraced more by Europeans than US critics because, although it’s a Hollywood film, it has a continental flair and distinctly European attitude toward sex.”

Other entries, such as Jacques Tati’s elaborate modernity-critiquing 70-millimeter spectacle Playtime, have also been received differently, to put it mildly, at different times and in different places. But if all comedy ultimately comes down to making us laugh, the only way to know your own position on the cultural comedic spectrum is to simply sit down and see what has that singularly enjoyable effect on you. Why not start with Keaton’s The General, which happens to be free to view online — and on some level the predecessor of (and, in the eyes of may critics, the superior of) even the physical comedies that come out today?

Related Content:

The Art of Making Intelligent Comedy Movies: 8 Take-Aways from the Films of Edgar Wright

The 10 Greatest Films of All Time According to 358 Filmmakers

The 10 Greatest Films of All Time According to 846 Film Critics

1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A Short Documentary on Artist Jeff Koons, Narrated by Scarlett Johansson

If you don’t move, nothing happens. — Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons, the subject of Oscar Boyson’s recent pop video essay, above, is surely one of the most widely known living artists. As with fellow artists Damien Hirst and Cindy Sherman the spotlight has produced an army of detractors who know very little about him, or his large, far-ranging body of work.

The choice of Scarlett Johansson to provide snarky second-person narration might not jolly Koons’ naysayers into suspending judgment long enough for a proper reintroduction. (His show-and-tell display of his Venus of Willendorf coffee mug causes her to quip, “You sexy motherfucker.” Ugh.)

On the other hand, there’s rapper Pharrell Williams’ onscreen observation that, “We need haters out there. They’re our walking affirmations that we’re doing something right.”

The potential for clamorous negative reaction has never propelled Koons to shy away from doing things on the grand scale in the public arena, as the giant open air display of such sculptures as “Seated Ballerina,” “Balloon Flower,” and “Puppy” will attest.

Surely, the genial affect he brings to the film is not what those who abhor “Made in Heaven,” a series of erotic 3‑D self-portraits co-starring his then-wife, porn-star Ilona “Cicciolina” Staller, would have expected.

Nor does he come off as a pandering, high priest of kitsch, something certain to disappoint those who abhor “Michael Jackson and Bubbles,” his gaudy, larger-than-life glazed porcelain sculpture of the King of Pop and his pet chimp.

“Kitsch is a word I really don’t believe in,” he smiles (possibly all the way to the bank).

Instead, he veers toward reflection, a fitting preoccupation for an artist given to mirror-polished stainless steel and more recently, gazing balls of the sort commonly found on 20th-century American lawns. He wants viewers to take a good look at themselves, along with his work.

Those whose hearts are set against him are unlikely to be swayed, but the undecided and open-minded might soften to a list of influences including Duchamp, Dali, DaVinci, Fragonard, Bernini, and Manet.

Ditto the opinions of a diverse array of talking heads like Frank Gehry, Larry Gagosian, and fellow post-modernist David Salle, who praises Koons’ artistic dedication to “everyday American-style happiness.”

Related Content:

John Waters: The Point of Contemporary Art

Teens Ponder Meaning of Contemporary Art

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

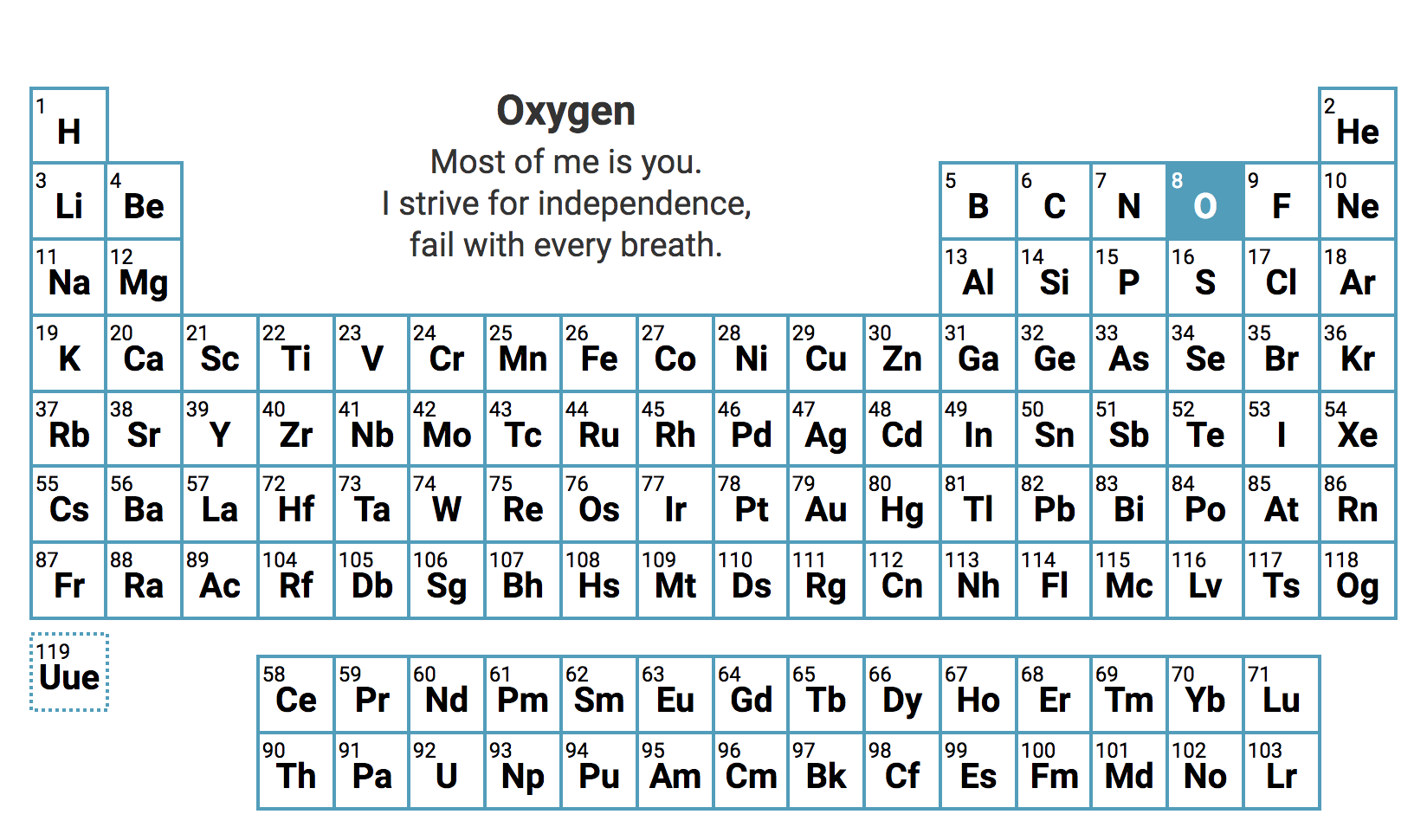

Read More...The Periodic Table of Elements Presented as Interactive Haikus

British poet and speculative fiction writer recently got a little creative with the Periodic Table, writing one haiku for each element.

Carbon

Show-stealing diva,

throw yourself at anyone,

decked out in diamonds.

Silicon

Locked in rock and sand,

age upon age

awaiting the digital dawn.

Strontium

Deadly bone seeker

released by Fukushima;

your sweet days long gone.

You can access the complete Elemental haiku here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

The Periodic Table of Elements Scaled to Show The Elements’ Actual Abundance on Earth

Periodic Table Battleship!: A Fun Way To Learn the Elements

“The Periodic Table Table” — All The Elements in Hand-Carved Wood

World’s Smallest Periodic Table on a Human Hair

“The Periodic Table of Storytelling” Reveals the Elements of Telling a Good Story

Chemistry on YouTube: “Periodic Table of Videos” Wins SPORE Prize

Free Online Chemistry Courses

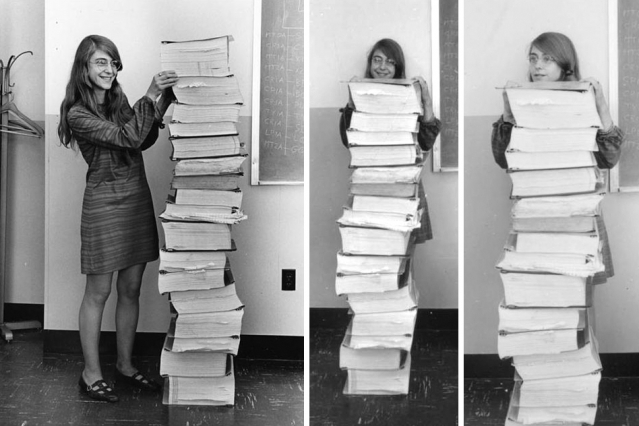

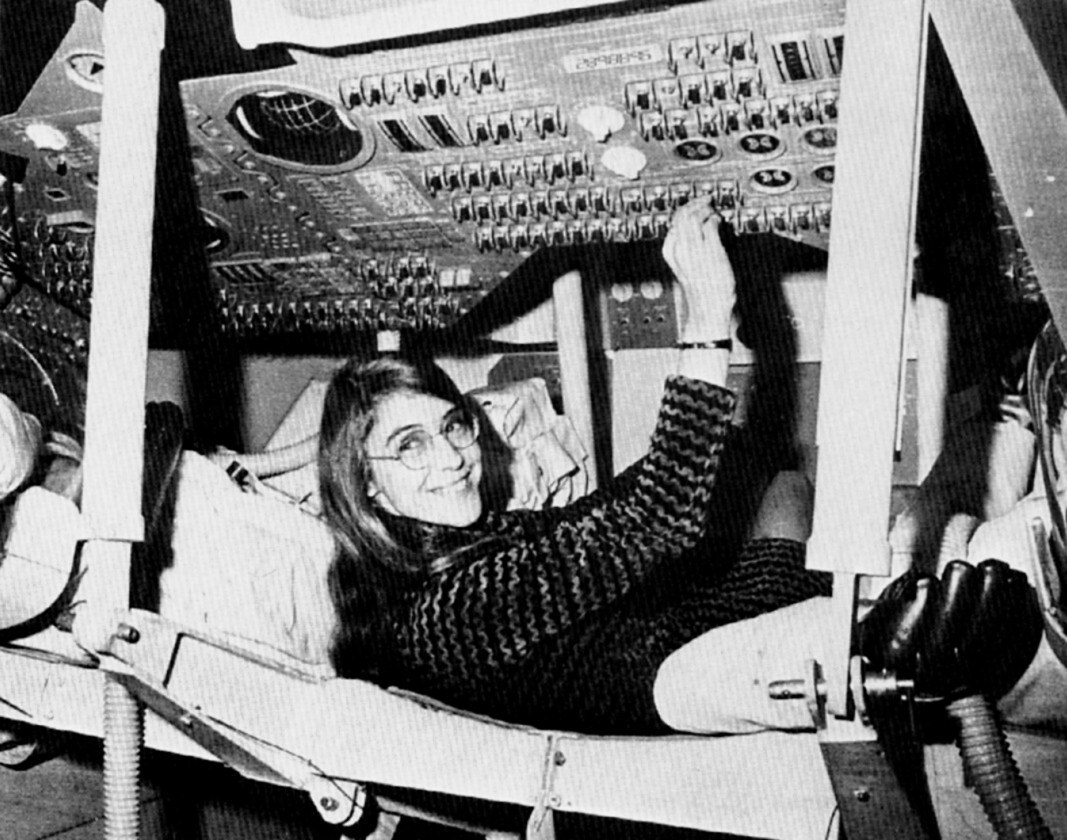

Read More...Margaret Hamilton, Lead Software Engineer of the Apollo Project, Stands Next to Her Code That Took Us to the Moon (1969)

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum

When I first read news of the now-infamous Google memo writer who claimed with a straight face that women are biologically unsuited to work in science and tech, I nearly choked on my cereal. A dozen examples instantly crowded to mind of women who have pioneered the very basis of our current technology while operating at an extreme disadvantage in a culture that explicitly believed they shouldn’t be there, this shouldn’t be happening, women shouldn’t be able to do a “man’s job!”

The memo, as Megan Molteni and Adam Rogers write at Wired, “is a species of discourse peculiar to politically polarized times: cherry-picking scientific evidence to support a pre-existing point of view.” Its specious evolutionary psychology pretends to objectivity even as it ignores reality. As Mulder would say, the truth is out there, if you care to look, and you don’t need to dig through classified FBI files. Just, well, Google it. No, not the pseudoscience, but the careers of women in STEM without whom we might not have such a thing as Google.

Women like Margaret Hamilton, who, beginning in 1961, helped NASA “develop the Apollo program’s guidance system” that took U.S. astronauts to the moon, as Maia Weinstock reports at MIT News. “For her work during this period, Hamilton has been credited with popularizing the concept of software engineering.” Robert McMillan put it best in a 2015 profile of Hamilton:

It might surprise today’s software makers that one of the founding fathers of their boys’ club was, in fact, a mother—and that should give them pause as they consider why the gender inequality of the Mad Men era persists to this day.

Hamilton was indeed a mother in her twenties with a degree in mathematics, working as a programmer at MIT and supporting her husband through Harvard Law, after which she planned to go to graduate school. “But the Apollo space program came along” and contracted with NASA to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s famous promise made that same year to land on the moon before the decade’s end—and before the Soviets did. NASA accomplished that goal thanks to Hamilton and her team.

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum

Like many women crucial to the U.S. space program (many doubly marginalized by race and gender), Hamilton might have been lost to public consciousness were it not for a popular rediscovery. “In recent years,” notes Weinstock, “a striking photo of Hamilton and her team’s Apollo code has made the rounds on social media.” You can see that photo at the top of the post, taken in 1969 by a photographer for the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. Used to promote the lab’s work on Apollo, the original caption read, in part, “Here, Margaret is shown standing beside listings of the software developed by her and the team she was in charge of, the LM [lunar module] and CM [command module] on-board flight software team.”

As Hank Green tells it in his condensed history above, Hamilton “rose through the ranks to become head of the Apollo Software development team.” Her focus on errors—how to prevent them and course correct when they arise—“saved Apollo 11 from having to abort the mission” of landing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon’s surface. McMillan explains that “as Hamilton and her colleagues were programming the Apollo spacecraft, they were also hatching what would become a $400 billion industry.” At Futurism, you can read a fascinating interview with Hamilton, in which she describes how she first learned to code, what her work for NASA was like, and what exactly was in those books stacked as high as she was tall. As a woman, she may have been an outlier in her field, but that fact is much better explained by the Occam’s razor of prejudice than by anything having to do with evolutionary determinism.

Note: You can now find Hamilton’s code on Github.

Related Content:

NASA Puts Its Software Online & Makes It Free to Download

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...