Last year, key works by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf finally entered the public domain, at least in Europe. (Find them in our collections of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books.) This year, we got pretty much bupkis, especially if we’re talking about the United States. Over at the website run by The Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke University, they write:

Last year, key works by James Joyce and Virginia Woolf finally entered the public domain, at least in Europe. (Find them in our collections of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books.) This year, we got pretty much bupkis, especially if we’re talking about the United States. Over at the website run by The Center for the Study of the Public Domain at Duke University, they write:

What is entering the public domain in the United States? Nothing. Once again, we will have nothing to celebrate this January 1st. Not a single published work is entering the public domain this year. Or next year. In fact, in the United States, no publication will enter the public domain until 2019. Even more shockingly, the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that Congress can take back works from the public domain. Could Shakespeare, Plato, or Mozart be pulled back into copyright? The Supreme Court gave no reason to think that they could not be.

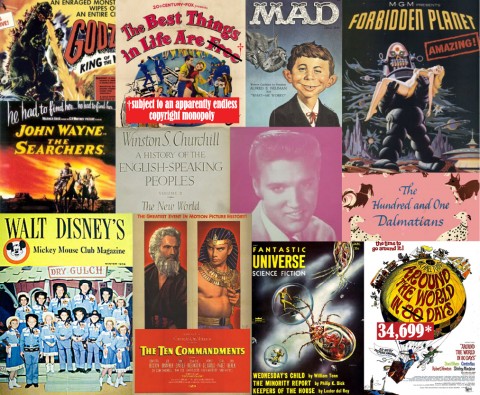

The Center then goes on to enumerate the works that would have entered the commons had we lived under the copyright laws that prevailed until 1978. Under those laws, “thousands of works from 1956 would be entering the public domain. They range from the films The Best Things in Life Are Free, Around the World in 80 Days, Forbidden Planet, and The Man Who Knew Too Much, to the Phillip K. Dick’s The Minority Report and Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, to seminal articles on artificial intelligence.” Have a look at some of the others, several of which appear in the mosaic above.

Related Content:

Lawrence Lessig’s Last Speech on Free Culture. Watch it Online.

Lawrence Lessig Speaks Once Again About Copyright and Creativity