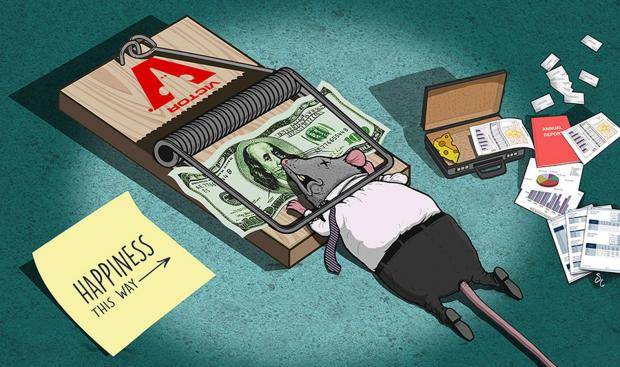

Illustrator Steve Cutts sets his latest animation, “Happiness,” in a teeming urban environment, with hundreds of near identical cartoon rats standing in for human drudges in an unfulfilling, and not unfamiliar race.

Packed subway cars, a bombardment of advertising, soul-deadening office jobs, and Black Friday sales are just a few of the indignities Cutts’ rodents are subjected to, to the tune of Bizet’s “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle.”

Rampant over-consumption—a major preoccupation for this artist—offers illusory relief, and a great deal of fun for viewers with the time to hit pause, to better savor the grim details.

The maximalist frames read like a gratifying perversion of Richard Scarry’s relentlessly sunny Busytown. As with Cutts’ 80s-throwback Simpson’s couch gag: pop-culture references and visual input whip by at subliminal warp speed.

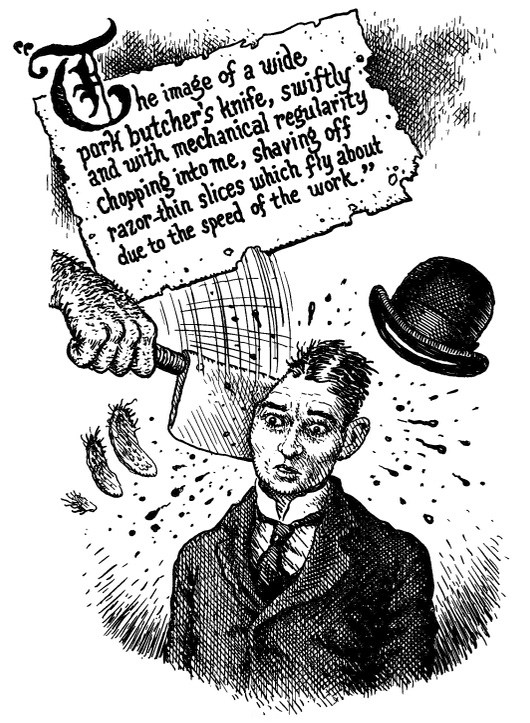

They may also serve as an antidote to the sort of messaging we’re constantly on the receiving end of, whether we live in city, country or somewhere in-between. Check out the scene as Cutts pans up from the subway platform, 52 seconds in:

The panty-clad female model for Blah cologne’s fashionably black and white ad is emaciated nearly to the point of death.

“You’re better than laces” flatters the latest (laceless) shoe from a swoosh-bedecked footwear manufacturer, while a radiator-colored beverage floats above the motto “Just drink it, morons.”

Krispo Flakes fight depression with “the bits other cereals don’t want.”

Heaven help us all, there’s even a poster for TRUMP The Musical.

This freeze-frame scrutiny could make an excellent activity for any class where middle and high schoolers are encouraged to think critically about their role as consumers.

As Cutts, a one-time employee of the digital marketing agency, Isobar, who contributed to campaigns for such global giants as Coca-Cola, Google, Reebok, and Toyota, told Reverb Press in 2015:

These are things that affect us all on a fundamental level so naturally they’re a main focus for a lot of my work. Humanity has the power to be great in so many ways and yet at the same time we are fundamentally flawed. I think it’s the conflict between these two that fascinates me the most. As a race of beings we’ve made incredible achievements in such a short space, but at the same time we seem so overwhelmingly intent on destroying ourselves and everything around us. It would be very interesting to see where we’ll be in a hundred years. The term insanity is intriguing – it’s almost like we’re encouraged to act in a way that seems genuinely insane when you look at it objectively, but it’s often accepted as normal right now. I think we will have to evolve beyond our current thinking and way of doing things if we want to survive.

See more of Cutts’ animated work here. And while he doesn’t go out of his way to hype his online store, a gallery quality print of The Rat Trap would make a fantastic gift from your cubicle mate’s Secret Santa. (HURRY! TIME IS RUNNING OUT!!!)

Related Content:

The Employment: A Prize-Winning Animation About Why We’re So Disenchanted with Work Today

Bertrand Russell & Buckminster Fuller on Why We Should Work Less, and Live & Learn More

Charles Bukowski Rails Against 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.