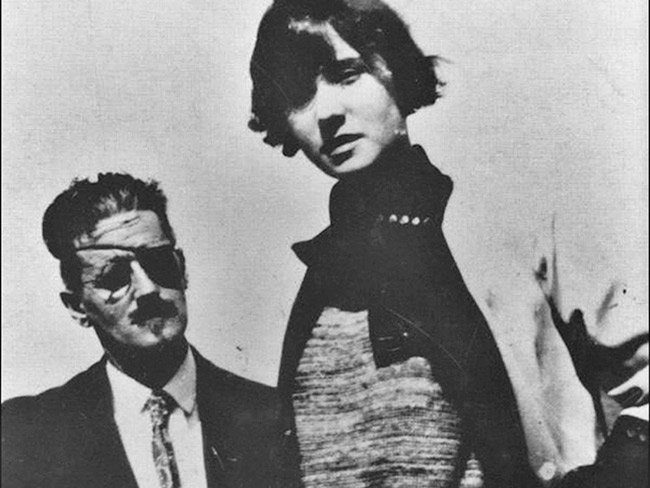

Today marks the 77th anniversary of Jim Henson’s birth. To celebrate the puppeteer, filmmaker, and Muppet inventor’s life and career, we offer here three of his early short works. Most of us know only certain high-profile pieces of Henson’s oeuvre: The Muppet Show, the Muppet movies, Sesame Street, or perhaps such pictures now much attended on the camp revival circuit as Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. But even by the Muppet Show’s 1974 debut, Henson (1936–1990) had already put in decades developing his distinctive aesthetic of puppets and puppetry. We’ve previously featured the uncharacteristically violent commercials he produced for Wilkins Coffee between 1957 and 1961 and Limbo, the Organized Mind, his seventies trip of a Johnny Carson segment. But unless you count yourself as a serious Henson, fan, you probably haven’t yet seen the likes of Memories, The Paperwork Explosion, and Ripples. Creating each of these shorts, the young Henson collaborated with pianist, jazz composer, and sound engineer Raymond Scott, now remembered as a pioneer in modern electronic music.

The particular sound of Scott, no stranger to scoring cartoons (we’ve by now heard it in everything from Looney Tunes to Ren and Stimpy to The Simpsons), also suited the sorts of visions Henson realized for his various projects of the sixties. Memories, which plunges into a man’s mind as he remembers (with narration by Henson himself) one particularly pleasant afternoon nearly ruined by a headache, appeared in 1967 as a continuation of Henson’s commercial career; the pain reliever Bufferin, you see, literally saved the day. That same year, the commercial (and in form, almost mini-documentary) The Paperwork Explosion illustrates the time- space‑, and labor-saving advantages of IBM’s then-new word-processing system, the MT/ST. Ripples Henson and Scott put together for Montreal’s Expo 1967. It takes place, like Memories and Limbo, inside human consciousness: an architect (Sesame Street writer-producer Jon Stone) drops a sugar cube in his coffee, and its ripples trigger a memory of throwing pebbles into a pond, which itself sends ripples through a host of his other potential thoughts. You’ve got to watch to understand how Henson and Scott pulled this off; conveniently, they only take one minute to do it.

For more early works by Henson, see this Metafilter post.

Related Content:

Jim Henson’s Animated Film, Limbo, the Organized Mind, Presented by Johnny Carson (1974)

Jim Henson’s Original, Spunky Pitch for The Muppet Show

Jim Henson Pilots The Muppet Show with Adult Episode, “Sex and Violence” (1975)

Jim Henson’s Zany 1963 Robot Film Uncovered by AT&T: Watch Online

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.