We’re fascinated by lists. Other people’s lists. Even the ones left behind in shopping carts are interesting (Jarlsburg, Gruyere and Swiss? Must be making fondue.) But it’s the lists made by famous people that are the really good stuff.

It’s fun to peek into the private musings of people we admire. Johnny Cash’s “To Do” list sold for $6,400 at auction a couple of years ago and inspired the launch of Lists of Note, an affectionate repository of personal reminders, commandments and advice jotted by celebrities and other notables.

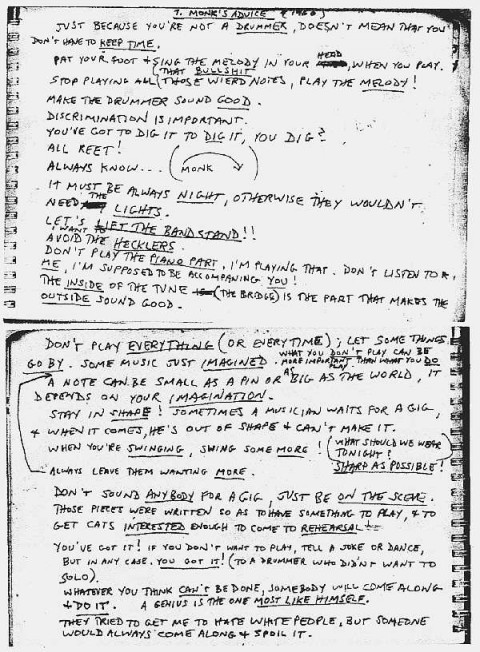

Most of the site’s best lists are in the “memo to self” category, some with tongue in cheek and others in earnest. But a few offer advice to others. Transcribed by soprano sax player Steve Lacy in a spiral-bound notebook, Thelonious Monk created a primer of do’s and don’ts for club musicians. For the greenhorns, Monk presented a syllabus for Band Etiquette 101 titled “1. Monk’s Advice (1960).” For the rest of us, it’s a view into one of the greatest, quirkiest minds of American music.

Some highlights:

“Don’t play the piano part. I’m playing that. Don’t listen to me. I’m supposed to be accompanying you!”

Monk himself was famous for his eccentricity—some say he was mentally ill and others blame bad psychiatric medications. He was known to stop playing piano, stand up and dance a bit while the band played on. But through his advice he reveals his fine sense of restraint.

“Don’t play everything (or every time); let some things go by. Some music just imagined. What you don’t play can be more important than what you do.”

Monk was evidently a stickler for band protocol. He leads his list with “Just because you’re not a drummer doesn’t mean that you don’t have to keep time!”

What should players wear to a gig? Definitively cool, Monk replies “Sharp as possible!” Read that as rings on your fingers, a hat, sunglasses and your best suit coat.

Here’s a transcript of the text:

- Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean that you don’t have to keep time.

- Pat your foot and sing the melody in your head when you play.

- Stop playing all that bullshit, those weird notes, play the melody!

- Make the drummer sound good.

- Discrimination is important.

- You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?

- All reet!

- Always know

- It must be always night, otherwise they wouldn’t need the lights.

- Let’s lift the band stand!!

- I want to avoid the hecklers.

- Don’t play the piano part, I am playing that. Don’t listen to me, I am supposed to be accompanying you!

- The inside of the tune (the bridge) is the part that makes the outside sound good.

- Don’t play everything (or everytime); let some things go by. Some music just imagined.

- What you don’t play can be more important than what you do play.

- A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.

- Stay in shape! Sometimes a musician waits for a gig & when it comes, he’s out of shape & can’t make it.

- When you are swinging, swing some more!

- (What should we wear tonight?) Sharp as possible!

- Always leave them wanting more.

- Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.

- Those pieces were written so as to have something to play & to get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal!

- You’ve got it! If you don’t want to play, tell a joke or dance, but in any case, you got it! (to a drummer who didn’t want to solo).

- Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along & do it. A genius is the one most like himself.

- They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along & spoil it.

Kate Rix is an Oakland-based freelancer. Find more of her work at .