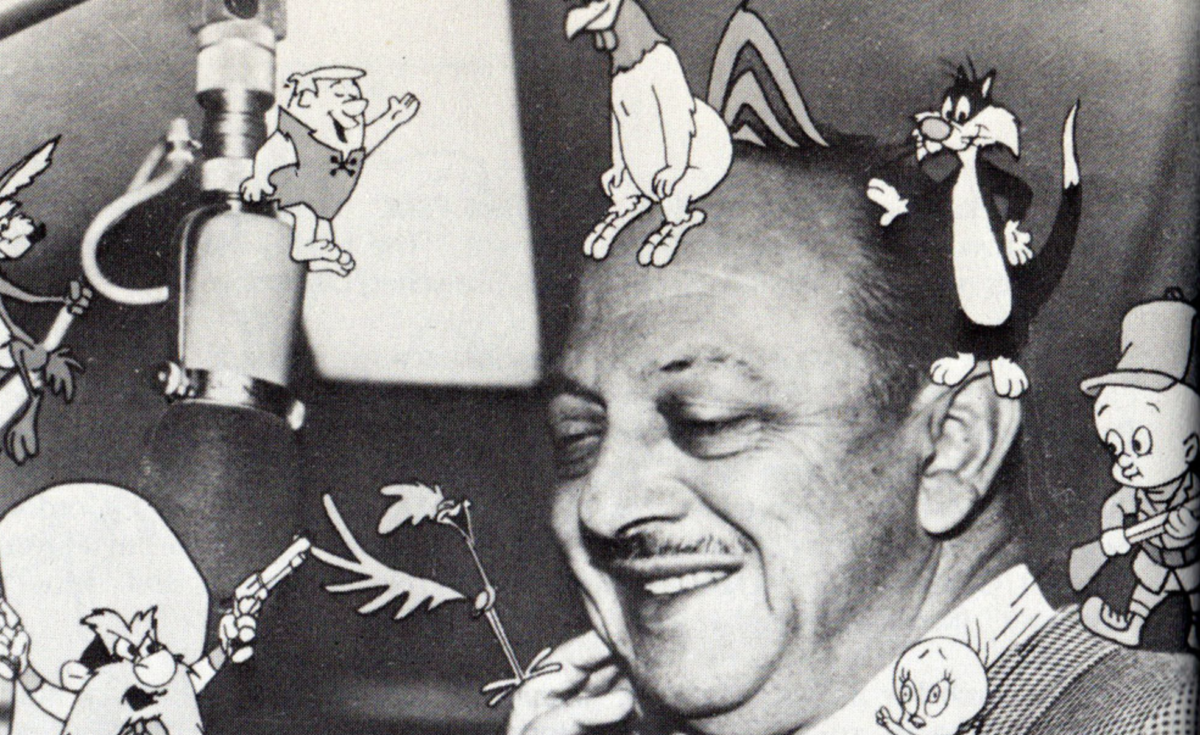

How does one read Twitter literature? Your thoughts are as good as mine. I suppose I’ll have to learn or end up in the ash heap of old-timey turners of pages. Because Twit Lit is upon us, manifested by Jennifer Egan and now, under the twitter handle “Bitchuation,” by mercurial filmmaker Steven Soderbergh. Having announced his retirement from filmmaking in 2011, Soderbergh made another announcement at the San Francisco Film Festival on the State of Cinema (video above, transcript here). The following day, Soderbergh’s Twitter novella Glue began with the laconic April 28 tweet “I will now attempt to tweet a novella called GLUE.”

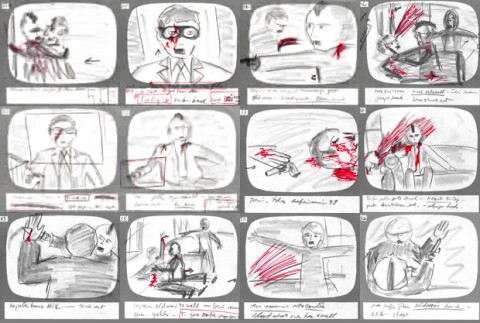

Some unique features of Twit Lit: Soderbergh can twitpic an establishing shot—which he does, of Amsterdam—along with pics of other locations (or just vaguely suggestive images). The individual tweets often read like Horse ebooks absurdities. He’s up to Chapter Fourteen now. The later tweets replicate screenplay dialogue, with copious insertions of BEAT to signify dramatic pauses. Taken together, I suppose there’s coherence, though as I admitted above, I have not mastered the ability to pull tweets together into longer text in my mind, Twitter being where I go when my attention span is spent.

I leave it to savvier, more patient readers to judge the success of Soderbergh’s attempt. It may suffice to say that his pessimism about the state of film does not apply to Twitter Lit. Or maybe he’s just passing time before he makes movies again.

Related Content:

Read, Hear, and See Tweeted Four Stories by Jennifer Egan, Author of A Visit from the Goon Squad

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness