The shibboleths of our political culture have trended lately toward the loathesome, crude, and completely specious to such a degree that at least one prominent columnist has summed up the ongoing spectacle in Cleveland as “grotesquerie… on a level unique in the history of our republic.” It’s impossible to quantify such a thing, but the sentiment feels accurate in the fervor of the moment. We’ll hear a torrent of well-worn counter-clichés at the other party’s big convention, and one of them that’s sure to come up again and again is the phrase “nation of immigrants.” The U.S., we’re told over and over, is a “nation of immigrants.” And it is. Or has become so, though the term “immigrant” is not an uncomplicated one, as we’ve seen in the EU’s struggle to parse “refugees” from “economic migrants.”

The U.S. is also a nation of indigenous people and former slaves, indentured servants, and settler colonists, all very different histories—and academic historians are careful not to blur the categories, even if politicians, ordinary citizens, and textbook publishers often do. Yet rhetoric about who owns the country, and who gets to “take it back,” clouds every issue—it belongs to everyone and no one, or as Wallace Stevens put it, “this is everybody’s world.”

But when we talk about the history of immigration, we usually talk about a specific history dating from the mid-19th to early-20th century, during which diverse groups of people arrived from all over the world, bringing with them their languages, customs, food, and cultures, and only slowly becoming “Americans” as they naturalized and assimilated to various degrees, forcibly or otherwise. We also talk about a legal history that proscribed certain kinds of people and created hierarchies of desirable and undesirable immigrants with respect to ethnic and national origin and economic status.

Millions of the people who arrived during the peak of U.S. immigration passed through the immigration inspection station at New York’s Ellis Island, which operated between the years 1882 and 1954. The individuals and families who spent any time there were working people and peasants. Among new arrivals, “the first and second class passengers were considered wealthy enough,” writes The Public Domain Review, “not to become a burden to the state and were examined onboard the ships while the poorer passengers were sent to the island where they underwent medical examinations and legal inspections.”

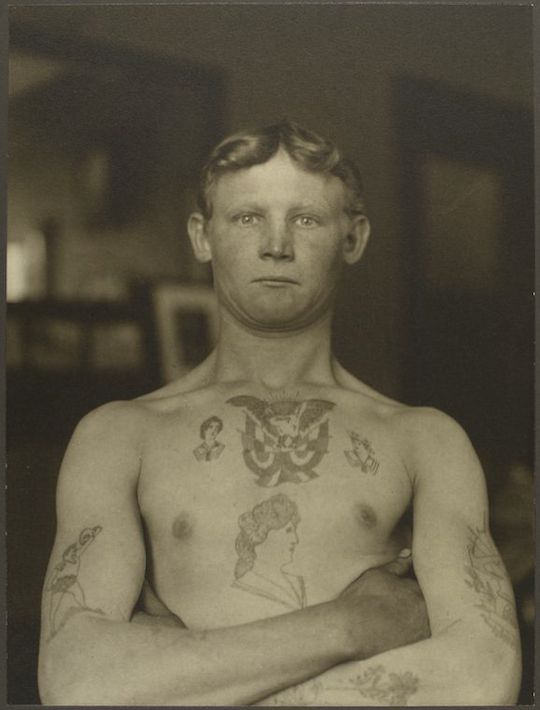

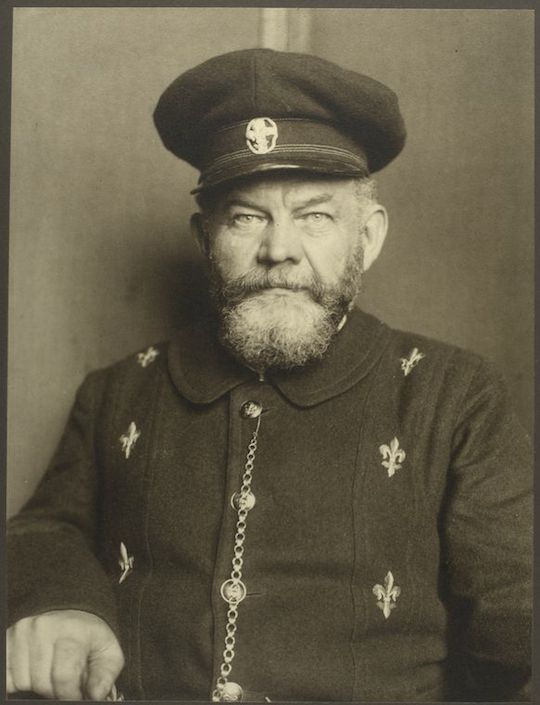

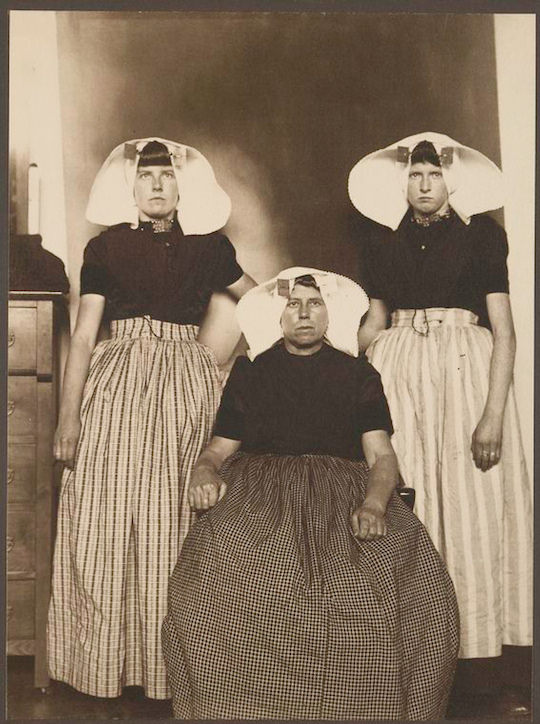

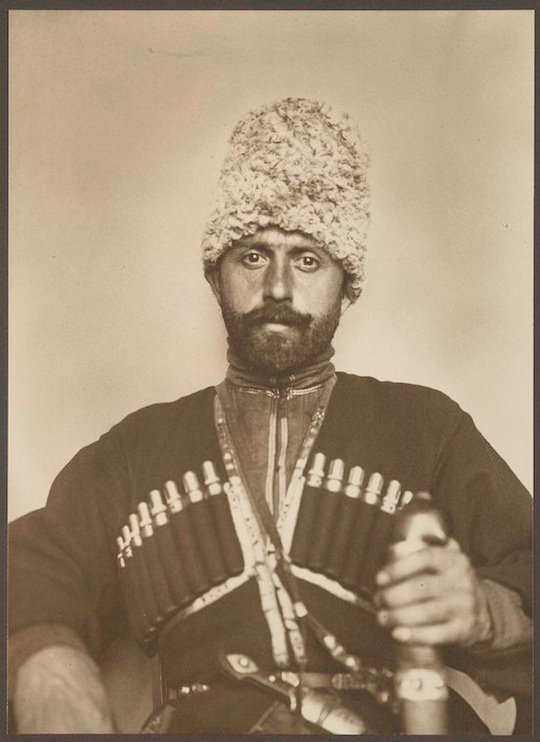

Many of these individuals also sat for portraits taken by the Chief Registry Clerk Augustus Sherman while “waiting for money, travel tickets or someone to come and collect them from the island.” Sherman’s camera captured striking images like the poised Guadeloupean woman in profile at the top, the defiant German stowaway below her, stern Danish man further down, Algerian man and Italian woman above, and severe-looking trio of Dutch women and Georgian man below.

These photographs date from before 1907, which was the busiest year for Ellis Island, “with an all-time high of 11,747 immigrants arriving in April.” About two percent of immigrants at the time were denied entry because of disease, insanity, or a criminal background. That percentage of people turned away rose in the following decade, and the diversity of people coming to the country narrowed significantly in the 1920s, until the 1924 immigration act imposed strict quotas, “as immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were seen as inferior to the earlier immigrants from Northern and Western Europe” and those from outside the European continent were limited to a tiny fraction of the almost 165,000 allowed that year.

“Following the Red Scare of 1919,” writes the Densho Encyclopedia, “widespread fear of radicalism fueled anti-foreign sentiment and exclusionist demands. Supporters of immigration legislation stressed recurring themes: Anglo-Saxon superiority and foreigners as threats to jobs and wages.” Not coincidentally, during this time the country also saw the resurgence of the Klu Klux Klan, which—notes PBS—“moved in many states to dominate local and state politics.” It was a time that very much resembled our own, sadly, as fanatical nativism and white supremacy became dominant strains in the political discourse, accompanied by much fearmongering, demagoguery, and violence. (It was also in the teens and twenties that the idea of a superior “Western Civilization” was invented.)

The portraits above were published in National Geographic and “hung on the walls of the lower Manhattan headquarters of the federal Immigration Service” in 1907, before the hysteria began. They show us the human face of an abstract phenomenon far too often used as an epithet or catch-all scare word rather than a fact of human existence since humans have existed. Becoming acquainted with the history of immigration in the U.S. allows us to see how we have handled it well in the past, and how we have handled it badly, and the photographic evidence preserves the dignity of the various individual people from all over the world who were lumped together collectively—as they are today—with the loaded word “immigrant.”

These images come from the New York Public Library’s online archive of Ellis Island Photographs, which contains 89 photos in all, including several exterior and interior shots of the island’s facilities and many more portraits of arriving people. We’re grateful to the Public Domain Review (who have a fascinating new book on Nitrous Oxide coming out) for bringing these to our attention. For more of the NYPL’s huge repository of historical photographs, see their Flickr gallery of over 2,500 photos or full digital photography collection of over 180,000 images.

Related Content:

478 Dorothea Lange Photographs Poignantly Document the Internment of the Japanese During WWII

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Leave a Reply