Taxis to Hell – and Back – Into the Jaws of Death, by Robert F. Sargent, via Wikimedia Commons

In the mid-20th century, theorists like Roland Barthes and Pierre Bourdieu exploded naive notions of photography as “a perfectly realistic and objective recording of the visible world… a ‘natural language,’” as Bourdieu wrote in Photography: A Middlebrow Art. Bourdieu himself wielded a camera during his ethnographic work in Algeria, taking dozens of conventional and unconventional photographs of the nation’s struggle for independence from France in the 50s. Yet he urged us to see photography as formally mediating social reality rather than transparently representing the truth.

We have been trained to interpret the perspectives most photographs adopt as objective views, when in fact they are “perfectly in keeping with the representation of the world which has dominated Europe since the Quattrocento.” Photography, in other words, tends to give us art imitating Renaissance art. It can be difficult to bear this in mind when we look at individual photographs—what Barthes calls “the This.”

Whether they document our own family histories or such momentous events as the Normandy Invasion that began on D‑Day, June 6th, 1944, photographs elicit powerful emotional reactions that defy aesthetic categories.

At the Flickr account PhotosNormandie, you can browse and search over 4,300 high resolution photographs from the pivotal Normandy campaign, “From iconic images like Into the Jaws of Death by Robert F. Sargent,” My Modern Met writes, “to troops interacting with locals as they liberate areas of Normandy.” The photos are deeply affecting, often awe-inspiring. When we look with a critical eye, we’ll find ourselves asking certain questions about them.

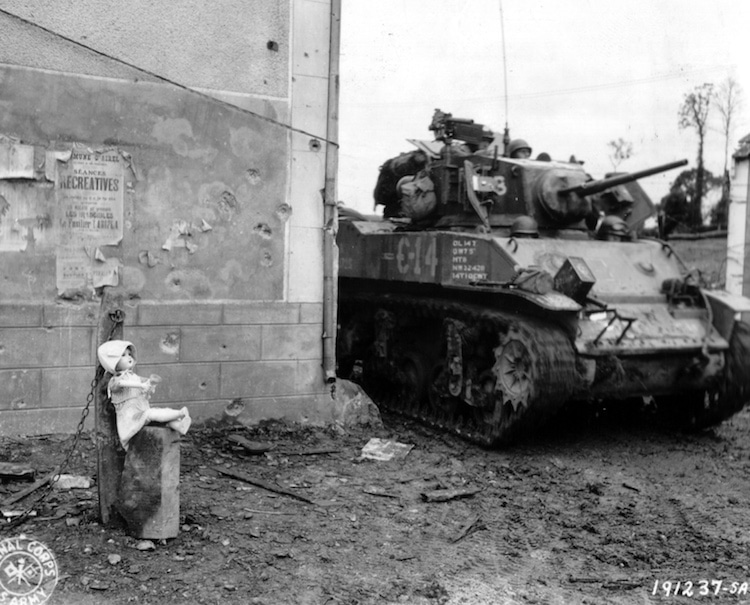

The skewed perspective and ominous sky in Sargent’s “Into the Jaws of Death,” for example, at the top of the post, might make us think of the Sturm und Drang of many a dramatic shipwreck painting from the Romantic period. Was Sargent aware of the similarity when he looked through the lens? Did he position himself to heighten the effect? In photos like that further up, of a French home displaying a pro‑U.S. sign on July 11th, 1944, we might wonder whether the residents made the sign or whether it was given to them, perhaps for this very photo op. As always, we’re justified in asking about the role of the photographer in staging or framing a particular scene.

For example, the photo of a German soldier surrendering to American G.I.s, above, looks staged. But what exactly these soldiers are doing remains a mystery. How much do these external details matter? Photography is unique among other visual arts in that “the Photograph,” Barthes writes, “reproduces to infinity” what has “occurred only once.” It is the meeting of infinity with “only once” that engages us in more existential explorations. All of these soldiers and civilians, sharing their joy and anguish, most of them now passed into history. Who were these people? What did these moments mean to them? What do they mean to us 70 years later?

The bombed-out cathedrals and defeated tanks make us ponder the fragility of our own built environment, though the destructive forces threatening to undo the modern world now seem as likely to be natural as man-made—or rather some new, frightening combination of the two. In the faces of the wounded and the displaced, we see specific manifestations of the same tragic invasions and migrations that reach back to Thucydides and forward to the present moment in world history, in which some 60 million people displaced by war and hardship seek sanctuary.

The images draw us away into general observations as they draw us back to the unrepeatable moment. This project began on the 60th anniversary of D‑Day “as a way,” My Modern Met explains, “to crowdsource descriptions of images on the now defunct Archives Normandie, 1939–1945. Thus, users are encouraged to comment on photos if they are able to improve descriptions, locations, and identifications.” History may rhyme with the present—as one famous quote attributed to Mark Twain has it—but it never exactly repeats. The photograph, Barthes wrote, “mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially.” Moments forever lost to time, transmuted into timelessness by the camera’s eye. Enter the PhotosNormandie gallery here.

via My Modern Met

Related Content:

The Finland Wartime Photo Archive: 160,000 Images From World War II Now Online

31 Rolls of Film Taken by a World War II Soldier Get Discovered & Developed Before Your Eyes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Men’s shoes chic but all too small sizes

I would not call those resolutions hi-res. Otherwise, great archive!