We might draw any number of conclusions from the fact that rats’ brains are enough like ours that they stand in for humans in laboratories. A misanthropic existentialist may see the unflattering similarity as evidence that there’s nothing special about human beings, despite our grandiose sense of ourselves. A medieval European thinker would draw a moral lesson, pointing to the rat’s gluttony as nature’s allegory for human greed. And a skeptical observer in the 19th and early 20th centuries might take note of how easily both rats and humans can be manipulated; the latter, for example, by pseudo-phenomena like Spiritualism, which encompassed a wide range of claims about ghosts and the afterlife, from seances to spirit photography.

One such skeptical observer in 1920, Millaias Culpin, even wrote in his Spiritualism and the New Psychology of the “’scientific’ supporters of spiritualism,” most of them “eminent in physical science.” They are easily convinced, Culpin thought, because “they have been trained in a world where honesty is assumed to be a quality of all workers. A laboratory assistant who played a trick upon one of them would find his career at an end, and ordinary cunning is foreign to them. When they enter upon the world of Dissociates, where deceit masquerades under the disguise of transparent honesty, these eminent men are but as babes—country cousins in the hands of confidence-trick men.”

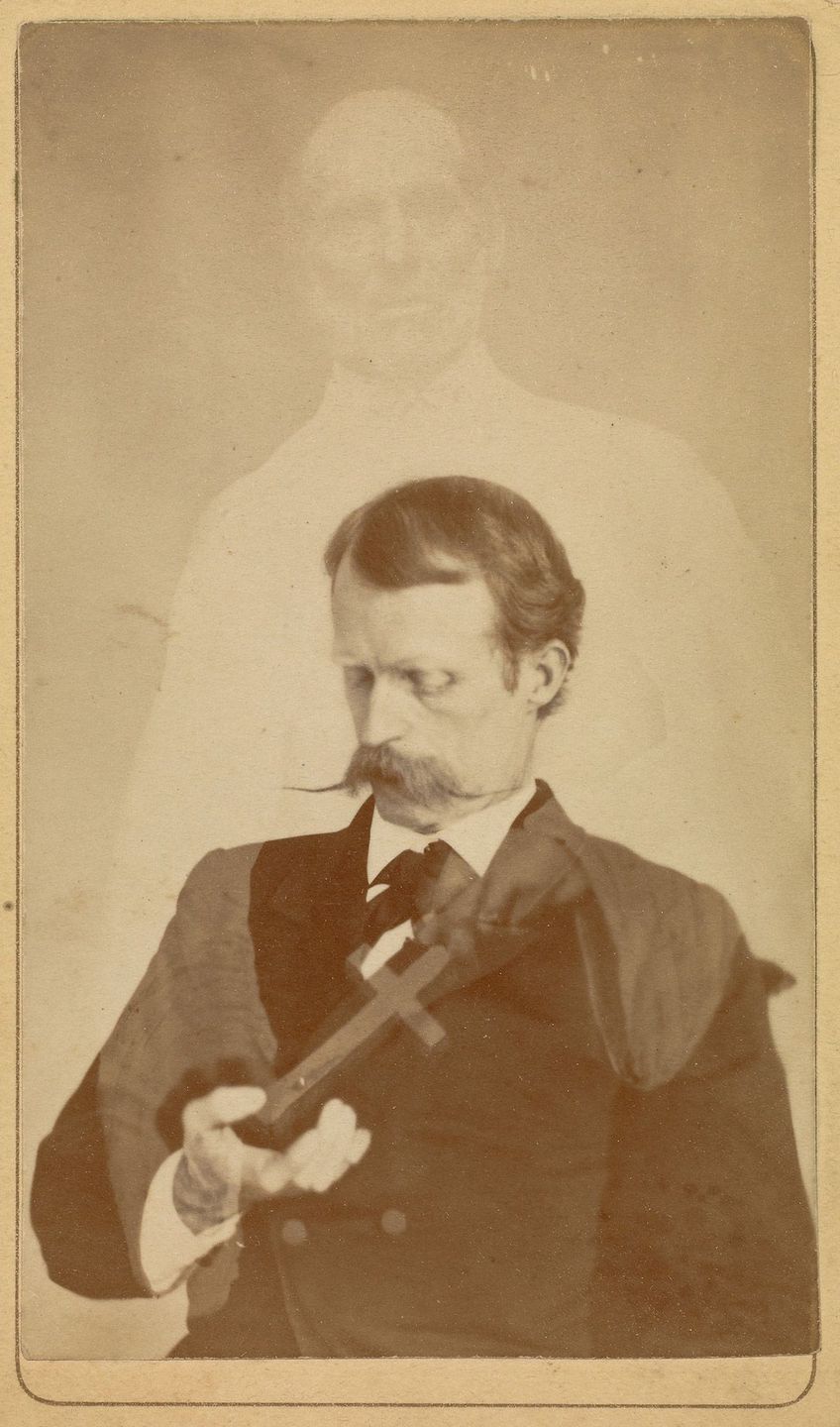

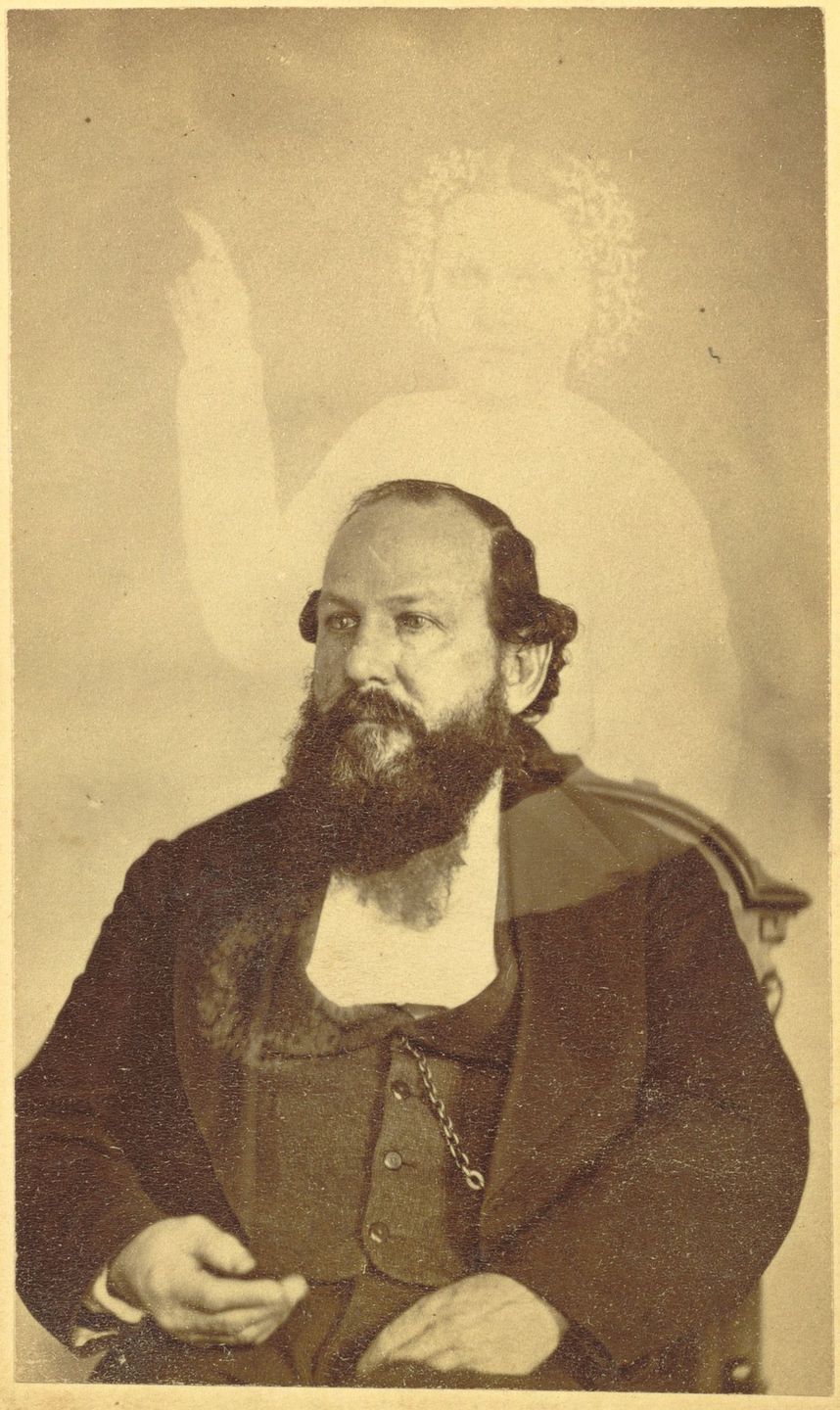

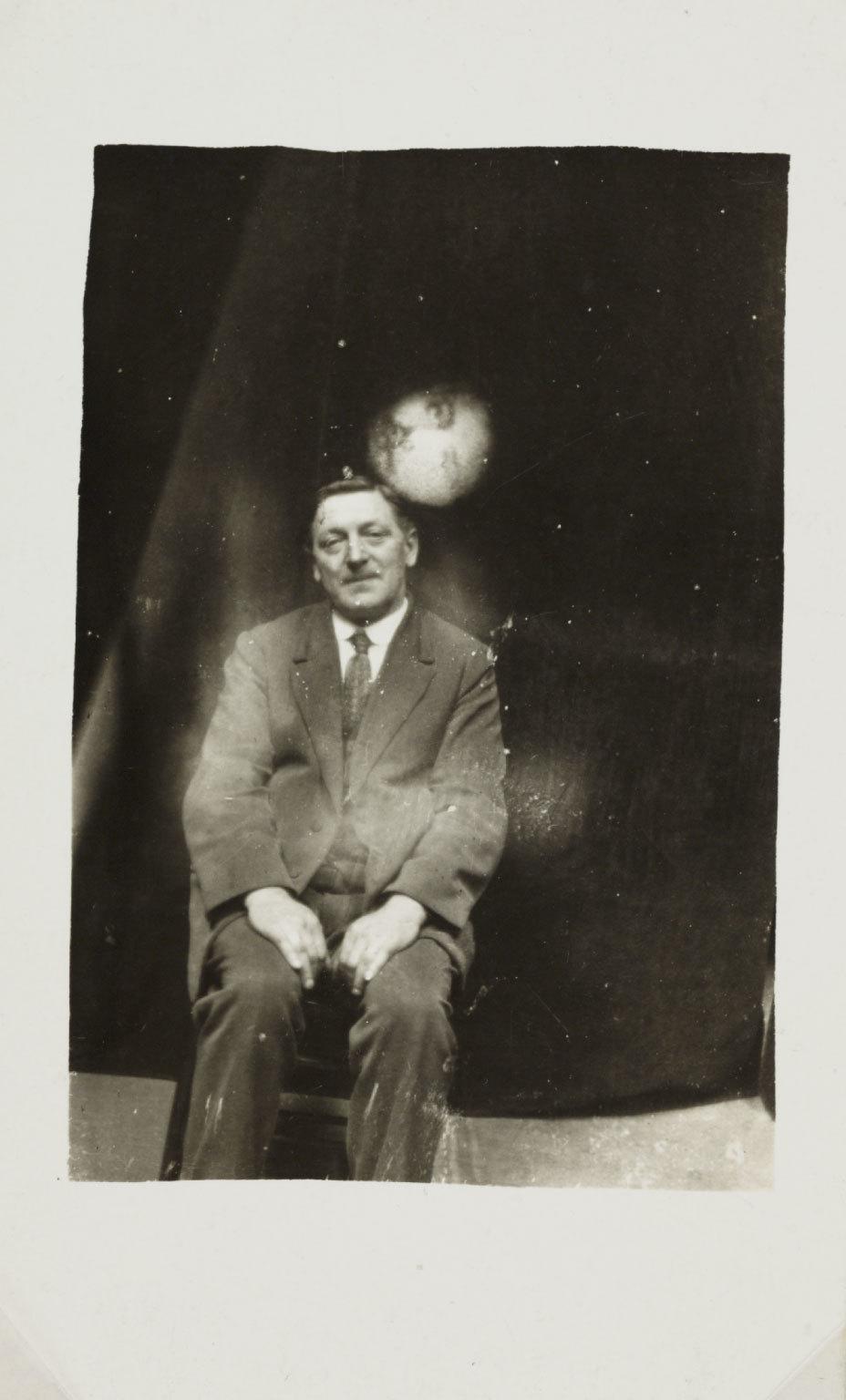

Such adherents of Spiritualist beliefs were taken in not because they were naturally credulous or stupid, but because they had been “trained” to trust the evidence of their senses. So-called spirit photographs, like those you see here, allowed people to “show material evidence for their beliefs.” Photographers who created the images, Mashable explains, could “easily make two exposures on a single negative, manipulate the negative to create ghostly blurs, or overlap two negatives in the darkroom to produce an extra face within the resultant frame.”

The audience for this work was “vast,” and many fit Culpin’s generalizations. In 1921, for example, paranormal investigator Hereward Carrington wrote of “a number of ‘spirit’ and ‘thought’ photographs, the evidence for which seemed to me to be exceptionally good.” In describing other pictures as “obviously fraudulent” or “extremely puzzling,” Carrington made critical distinctions and appeared to use the methods and the language of science in the evaluation of objects purporting to prove the existence of ghosts.

It may seem incredible that spirit photography had widespread appeal for as long as it did. The photographs first began appearing in the 1860s, emerging “from a small Boston portrait studio” and first made by William H. Mumler, the genre’s inventor and “most prominent early proponent,” writes Mashable.

Mumler was neither a photographer nor a medium. He originally worked as a silver engraver, while dabbling in photography in the local studio of a woman named Mrs. Stuart. One day in 1861, in the midst of developing a self-portrait, Mumler reported that the dim figure of a young cousin who had died twelve years earlier emerged in the final print.

These ghostly images continued to appear—on their own, the story goes—and the studio’s receptionist, a part-time medium, helped popularize them. Soon Mumler “received visitors from across America, including the recently widowed Mary Todd Lincoln.” Most of these visitors did not work as scientists or professional paranormal investigators. They were ordinary people bereaved by the mass death of the Civil War and deeply motivated to accept physical confirmation of an afterlife. Moreover, before the rise of Fundamentalist Evangelicalism in the 1920s, Spiritualism was on the front lines of an earlier culture war: spirit photography was “a tangible symbol of the overarching argument of mysticism versus science and rationalism.”

The three images at the top of the post date from the earliest period of spirit photography, between 1862 and 1875, and they were all produced by Mumler in Boston and New York, where he moved in 1869, and where he was charged with fraud, then “acquitted of all charges because they could not be sufficiently proven.” (See many more of his photos at Mashable and the Getty Museum online archive.) Though his business suffered, spirit photography only grew more popular, particularly in Spiritualist circles in Britain, where Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the hyper-rational Sherlock Holmes, was one of the most ardent of Spiritualist believers.

Doyle supported a British photographer named William Hope, who began taking spirit photographs in 1905, founded a group called the Crewe Circle and later “went on to prey on grieving families,” writes River Donaghey at Vice, “who lost loved ones in WWI and desperately wanted photographic proof that their relatives were still hovering around in spectral form.” Even after Hope and his crew were exposed, Doyle continued to support him, going so far as to write a book called The Case for Spirit Photography. The four photographs above and below are Hope’s work (see many more at Vice and the Public Domain Review). They are seriously creepy—in the way movies like The Ring are creepy—but they are also, quite obviously, photographic fictions.

Even as viewers of photography became savvier as the century wore on, many people thrilled to Hope’s work until his death in 1933, maybe for the same reason we watch The Ring; it’s a fun scare, nothing more, if we suspend our disbelief. As for the true believers in spirit photography—they are not so different either from us 21st century sophisticates. We’re still taken in all the time by hoaxes and frauds, maybe because it’s still as easy to push the buttons in our brains, and because, well, we just want to believe.

Related Content:

Browse The Magical Worlds of Harry Houdini’s Scrapbooks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply