Rochester Institute of Technology, via Wikimedia Commons

Everyone should read the Bible, and—I’d argue—should read it with a sharply critical eye and the guidance of reputable critics and historians, though this may be too much to ask for those steeped in literal belief. Yet fewer and fewer people do read it, including those who profess faith in a sect of Christianity. Even famous atheists like Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and Melvyn Bragg have argued for teaching the Bible in schools—not in a faith-based context, obviously, but as an essential historical document, much of whose language, in the King James, at least, has made major contributions to literary culture. (Curiously—or not—atheists and agnostics tend to score far higher than believers on surveys of religious knowledge.)

There is a practical problem of separating teaching from preaching in secular schools, but the fact remains that so-called “biblical illiteracy” is a serious problem educators have sought to remedy for decades. Prominent Shakespeare scholar G.B. Harrison lamented it in the introduction to his 1964 edited edition, The Bible for Students of Literature and Art. “Today most students of literature lack this kind of education,” he wrote, “and have only the haziest knowledge of the book or of its contents, with the result that they inevitably miss much of the meaning and significance of many works of past generations. Similarly, students of art will miss some of the meaning of the pictures and sculptures of the past.”

Though a devout Catholic himself, Harrison’s aim was not to proselytize but to do right by his students. His edited Bible is an excellent resource, but it’s not the only book of its kind out there. In fact, no less a luminary, and no less a critic of religion, than scientist and sci-fi giant Isaac Asimov published his own guide to the Bible, writing in his introduction:

The most influential, the most published, the most widely read book in the history of the world is the Bible. No other book has been so studied and so analyzed and it is a tribute to the complexity of the Bible and eagerness of its students that after thousands of years of study there are still endless books that can be written about it.

Of those books, the vast majority are devotional or theological in nature. “Most people who read the Bible,” Asimov writes, “do so in order to get the benefit of its ethical and spiritual teachings.” But the ancient collection of texts “has a secular side, too,” he says. It is a “history book,” though not in the sense that we think of the term, since history as an evidence-based academic discipline did not exist until relatively modern times. Ancient history included all sorts of myths, wonders, and marvels, side-by-side with legendary and apocryphal events as well as the mundane and verifiable.

Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, originally published in two volumes in 1968–69, then reprinted as one in 1981, seeks to demystify the text. It also assumes a level of familiarity that Harrison did not expect from his readers (and did not find among his students). The Bible may not be as widely-read as Asimov thought, even if sales suggest otherwise. Yet he does not expect that his readers will know “ancient history outside the Bible,” the sort of critical context necessary for understanding what its writings meant to contemporary readers, for whom the “places and people” mentioned “were well known.”

“I am trying,” Asimov writes in his introduction, “to bring in the outside world, illuminate it in terms of the Biblical story and, in return, illuminate the events of the Bible by adding to it the non-Biblical aspects of history, biography, and geography.” This describes the general methodology of critical Biblical scholars. Yet Asimov’s book has a distinct advantage over most of those written by, and for, academics. Its tone, as one reader comments, is “quick and fun, chatty, non-academic.” It’s approachable and highly readable, that is, yet still serious and erudite.

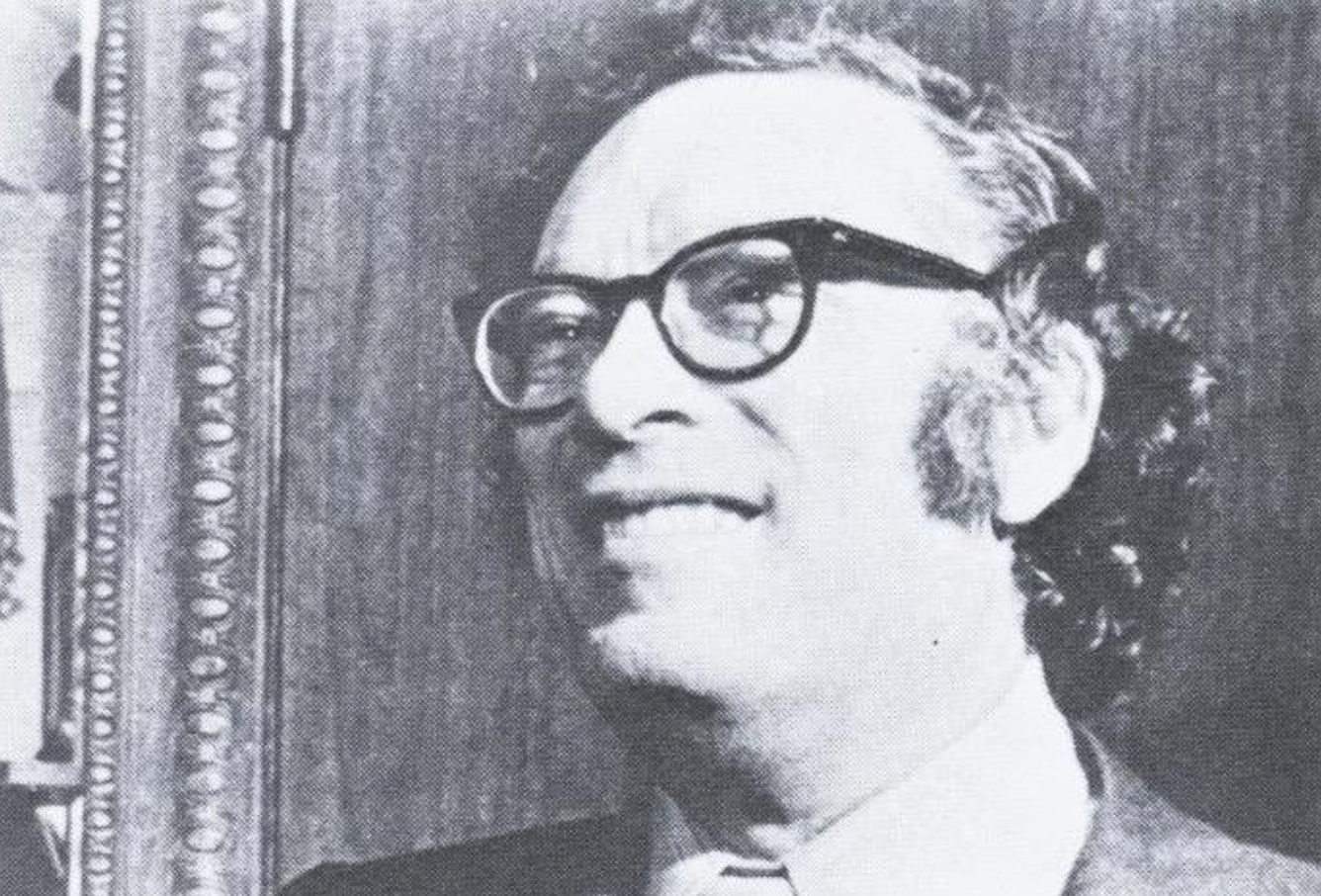

Asimov’s approach in his guide is not hostile or “anti-religious,” as another reader observes, but he was not himself friendly to religious beliefs, or superstitions, or irrational what-have-yous. In the interview above from 1988, he explains that while humans are inherently irrational creatures, he nonetheless felt a duty “to be a skeptic, to insist on evidence, to want things to make sense.” It is, he says, akin to the calling believers feel to “spread God’s word.” Part of that duty, for Asimov, included making the Bible make sense for those who appreciate how deeply embedded it is in world culture and history, but who may not be interested in just taking it on faith. Find an old copy of Asimov’s Guide to the Bible at Amazon.

Related Content:

Introduction to the Old Testament: A Free Yale Course

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

https://archive.org/details/AsimovsGuideToTheBibleTheOldAndNewTestaments2Vols.IsaacAsimov

My personal feeling is that Asimov had a real misanthropic streak to him, and was sort of a phony. Completely lacking in humility. Clever, intelligent, sure…sincere, not so much. His professions seem characteristic of someone needing a lot of approval. I would love to hear from his former students because that has got to be a difficult disposition to hold for any length of time. Perhaps it is just the humanism. I will never get the arrogance of that.

A sci-fi geek in my teens and pre-salvation, I was given this book by a Christian who hadn’t read it. I made an attempt, but it was basically Asimov discounting events because this couldn’t happen and that couldn’t have happened. A pseudo-intellectual approach by a man afraid. One of the first books I tossed in the trash.

I read the 1981 edition in the 90’s, and still treasure it. Go back to it every time I come across a Bible reference I’m not so familiar with. It’s an excellent resource. I became a fan toward the end of Asimov’s life and didn’t get the opportunity to meet him, but in the many interviews I’ve watched, he comes off as very genuine. I take issue with the other comments. Even at its monstrous length, this is a very worthwhile book.

I only have his guide to the new testament. I used it to prepare for Jehova’s witness visits. They did not like it at all. Very respectful conversations, just offering another interpretation of events. After less than ten visits they were fine for years.

Love it for the respectful approach of the Book. His timelines were very illuminating. I also use it to challenge my own belief and make my own conclusions. It makes the Bible more inspiring than literal. Though parts should be read literally. Asimov enhances the knowledge part. You can use that for your developing wisdom.

“Scientific Consensus” is an oxymoron. Nation States are as important as our individual freedoms. A One world government would only create endless pain and suffering for the masses like all centralized governments where absolute power corrupts absolutely.

“Liberated from Religion” and “Wasting Time on God”, by Paulo Bitencourt, are the books I recommend on Freethought, Humanism and Atheism.

I assume the reason they stopped visiting you might have been you wasn’t that interested in studying the bible.

A thought. In case you think there is no God, no Creator — and before the universe started to exist, there was nothing. If so, why is there still not nothing?

As I understand it, many atheists believe ( yes it is a matter of belief) that everything that exists came from nothing, that the nothingness transformed it selv to be something.

And they feel that the thought that there is no God is comforting to them. So, just as a thought experiment. In case that there is no God, that God is nothing because that God doesn’t exist, couldn’t everything come from God?

In case you want to get tons of logical arguments for concluding that there really is a Creator, Jehovah’s witnesses can give you solid, logical information. Of course, people do not have to be Jehovah’s witnesses to conclude that there is a God. (If you find a fork on the pavement you might not know who made it, but you will logically conclude it was made.)

But if you also want to get accurate bible knowledge — talk to Jehovah’s witnesses, the true christians :)

I would \recommend American Atheist :The Bible Handbook” as the best I have found along with “Arsenal for Skeptics” by Hinton and it was the first I had read and that was after going through the Bible in the 1950s and taking a lot of notes.

The Bible says killing everyone in 66 cities plus all the animals is fine to make way for the Jews. After “thou shalt not kill” there are many killing claim by an actually non-existing “God” who is not the god for everyone but just for the Jews. This God in Judges 1:19 can not defeat the people in the valley because they have chariots of iron! Early in the O.T he sits on a Mercy Seat in a special place in a huge tent. Later he lives in the Temple in Jerusalem in the Holy of Hollies. Then Babylon attacks and destroys the Temple and the Ark of the Covenant is heard of no more. The God did not exist anyway but could not defend Jerusalem. Israel paid tribute to at least three more powerful countries in the region. The book exaggerates throughout. There was no real “Garden of Eden” nor was there a Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil or any Adam and Eve and people never lived for centuries as Bible claims of over 960 years, Jews were never enslaved in Egypt that is a myth. Myths and lies make up so much of the OT and NT> How when some more than 60 Jewish writers never wrote about any Jesus character nor could the gospel writers who quoted Jesus as if that was possible many decades after first may have lived. A horrible book. Can Christian read? 81 Bill Bolinger life long nonbeliever‑a naturalist.

The late Dr. Asimov’s take on Revelation 7 has got to be essential reading. “This [list of the tribes of Israel] is a strange list” and “[some] people are unable to accept something as prosaic as a copyist’s error in the Bible.”

I had an astronomy professor at UC Berkeley who said that knowing about Rev. 7 is essential; ditto for a nursing professor at the state hospital outside Petersburg, Virginia who wore a badge identifying himself as “Anton LaVey”, but this cannot be: LaVey was the name of a famous Satanist who died in 1997.