When I order a cup of tea in Korea, where I live, I ask for cha (차); when traveling in Japan, I ask for the honorific-affixed ocha (お茶). In Spanish-speaking places I order té, which I try to pronounce as distinctly as possible from the thé I order in French-speaking ones. And on my trips back to United States, where I’m from, I just ask for tea. Not that tea, despite its awe-inspiring venerability, has ever quite matched the popularity of coffee in America, but you can still find it most everywhere you go. And for decades now, no less an American corporate coffee juggernaut than Starbucks has labeled certain of its teas chai, which has popularized that alternative term but also created a degree of public confusion: what’s the difference, if any, between chai and tea?

Both words refer, ultimately, to the same beverage invented in China more than three millennia ago. Tea may now be drunk all over the world, but people in different places prefer different kinds: flavors vary from region to region within China, and Chinese teas taste different from, say, Indian teas. Starbucks presumably brands its Indian-style tea with the word chai because it sounds like the words used to refer to tea in India.

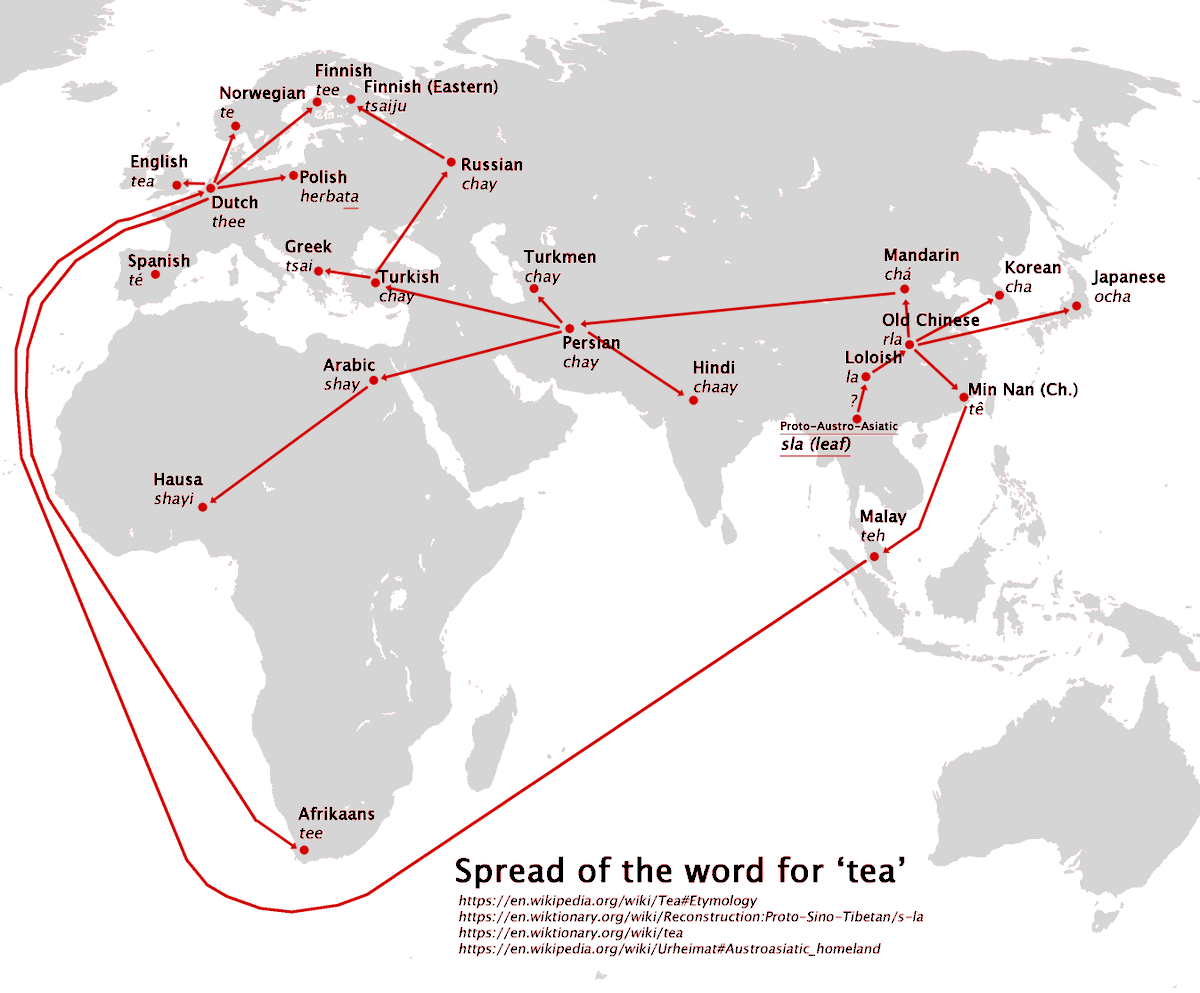

It also sounds like the words used to refer to tea in Farsi, Turkish, and even Russian, all of them similar to chay. But other countries’ words for tea sound different: the Maylay teh, the Finnish tee, the Dutch thee. “The words that sound like ‘cha’ spread across land, along the Silk Road,” writes Quartz’s Nikhil Sonnad. “The ‘tea’-like phrasings spread over water, by Dutch traders bringing the novel leaves back to Europe.”

“The term cha (茶) is ‘Sinitic,’ meaning it is common to many varieties of Chinese,” writes Sonnad. “It began in China and made its way through central Asia, eventually becoming ‘chay’ (چای) in Persian. That is no doubt due to the trade routes of the Silk Road, along which, according to a recent discovery, tea was traded over 2,000 years ago.” The te form “used in coastal-Chinese languages spread to Europe via the Dutch, who became the primary traders of tea between Europe and Asia in the 17th century, as explained in the World Atlas of Language Structures. The main Dutch ports in east Asia were in Fujian and Taiwan, both places where people used the te pronunciation. The Dutch East India Company’s expansive tea importation into Europe gave us the French thé, the German Tee, and the English tea.”

And we mustn’t leave out the Portuguese, who in the 1500s “travelled to the Far East hoping to gain a monopoly on the spice trade,” as Culture Trip’s Rachel Deason writes, but “decided to focus on exporting tea instead. The Portuguese called the drink cha, just like the people of southern China did,” and under that name shipped its leaves “down through Indonesia, under the southern tip of Africa, and back up to western Europe.” You can see the global spread of tea, tee, thé, chai, chay, cha, or whatever you call it in the map above, recently tweeted out by East Asia historian Nick Kapur. (You may remember the fantastical Japanese history of America he sent into circulation last year.) Study it carefully, and you’ll be able to order tea in the lands of both te and cha. But should you find yourself in Burma, it won’t help you: just remember that the word there is lakphak.

Related Content:

An Animated History of Tea

1934 Map Resizes the World to Show Which Country Drinks the Most Tea

10 Golden Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea (1941)

George Orwell’s Rules for Making the Perfect Cup of Tea: A Short Animation

Epic Tea Time with Alan Rickman

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Hello.

The history you mention wouldn’t exist, at least not as it is, without the portuguese contribuition, which brought tea from the far east (as you mention, but only in the end), and spread it in west, firstly introducing it in England, where the 5pm tea tradition appeared because a portuguese princess always took it at that time and, being in England, the habbit remained there in the english court.

Also portuguese call tea chá, like the easterns, something you also mention only in the end, but one can’t see in the infographic.

Just wanted to clear this out, because one could think tea came to west “with the wind”, when in fact, this journey has a history.

P.S. I know this is based on another article, but I think in this website things should be more in depth.

Paulo Colaço, portuguese chá lover.

It’s funny that many places in this map show the presence of variations of “chá”, but not who were the navigators who carried this word around: the Portuguese

The Spanish, French, German and English words are all (or in the case of English, used to be) pronounced in the same way, i.e. tay. This pronunciation is still ‘live’ in many dialects of English.

Here’s a couplet from Pope’s mock-epic, ‘The Rape of the Lock’ ((III.7–8)), which shows you how the word was pronounced in the early 18th century:

Here Thou, Great Anna, Whom three Realms obey,

Dost sometimes Counsel take—and sometimes Tea.

This article (it is written in Portuguese) states that TEA stands for Transporte de Ervas Aromáticas ( Aromatic Herbs Transport). The letters TEA were written in the boxes shipped to England during Portugal’s long and awful colonial activity. The portuguese word is “chá”.

http://visao.sapo.pt/actualidade/sociedade/2017–08-28-A-historia–portuguesa–por-detras-da-obsessao-dos-ingleses-pelo-cha

Your understanding of the use chai in Starbucks is incorrect. It’s not just branding, it was used well before Starbucks started selling it and is in fact then name of a particular tea beverage, although you are correct in staring that it’s origins are in india. In India they characteristicly make their tea by boiling black tea for a while along with a spice mix including cinnamon and mace, sometimes black pepper etc, it’s milky and also very sweetened. It’s like a warm Christmas-spices sweet beverage with tea undertones. Chai in a western English speaking situation means this kind of tea only, to the extent that many times I’ve seen it referred to as ’ chai tea’ despite that translating as ’ tea tea ‘. It might have been that if both cultures used a similar word for tea it might be called ‘Indian tea’ to differentiate, but for most people ‘chai’ has suffised. It might be like ordering an Americano and knowing that refers to.a.particular way of serving coffee. I don’t know why this irked me enough to bother commenting, I suppose because it was hippies, travellers and free thinkers who were drinking chai tea well before Starbucks got their claws in with their syrupy fake tea that is nothing like the intended thing, and to call it branding is so incorrect and is as silly as to imagine that a cappuccino refers to all types of coffee.

As mentioned before in the comments, the article is factually wrong: more than two centuries before the Dutch East India company, the Portuguese were trading tea — that they called then, as we still do now, “chá” — from the Far East to Europe (together with valuable spices).

There is a widespread story how the “T” (initial from the word tchai) the Portuguese painted the boxes containing tea would eventually become synonym with the beverage in all of the Western European languages EXCEPT Portuguese.

And there is also the apparently truthful story on how tea (along with marmalade and tobacco) was introduced in the English royal environment by a Portuguese consort, Catarina, who would marry Charles II.

None of this appears in the misleading article… Back to the library for the author.

Unfortunately, your information is biased, wrong and ill-intentioned based on ignorance.

The article is full of

Just because you read something in an article doesn’t mean it’s right.

That TEA word is related to that because it was the initials on one of Queen’s Catherine chests that she brought to England to be married to Charles II.

In Portuguese, tea (the drink) is called chá. The Portuguese introduced tea into the Western world, namely to the Ul and other countries through their world commerce from China, in Macao, Portuguese territory given to them by the Emperor of China in the mid-1500s, being the Portuguese the first Westerners to arrive in Asia.

The Portuguese Empire was an empire of its time, and you can’t take it out of this frame. If you do so, you must judge all world history empires by the same prisma. The Portuguese empire gave extraordinary knowledge, culture, advancement in science, and the Japanese Renaissance, among many other facts that can be found in reliable sources.

It was, for instance, due to the Portuguese Queen, Catherine of Braganza, that the British advanced and expanded as powerfully as they did then. In her dowry, she brought to the British crown, among monetary reaches and geographical offerings — Bombay and others — the right to free trade with all the Portuguese territories. It permitted the British Empire to expand, as was the case in India.

It is true that in those times, what today is considered unacceptable it was not. As it was in the time of the Romans, the Egyptians, the Mongols, the Chinese, the Ottomans, and the Babilons, to name a few…

I hope this will help enlighten you and awaken your curiosity to look further with an open mind and acute intelligence.

This adds to what others have written here to correct this fake news and misinformation…