Image by Clemens Pfeiffer via Wikimedia Commons

The first computer I ever sat before, the 1983 Apple IIe, had a manual the size of a textbook, which included a primer on programming languages and a chapter entitled “Getting Down to Business and Pleasure.” By “pleasure,” Apple mostly meant “electronic worksheets,” “word processors,” and “database management.” (They hadn’t fully established themselves as the fun one yet.) Getting these programs running took real effort and patience, especially compared to the MacBook Air on which I’m typing now.

All those old tedious processes are automated, and no more do we need manuals—we’ve got the internet, which also happens to be the only way I could operate an Apple IIe, whether that means tracking down a manual on eBay or finding a scanned copy somewhere online. Luckily, for vintage Apple enthusiasts, this isn’t difficult, and someone with rudimentary knowledge of Apple DOS could muddle through without one.

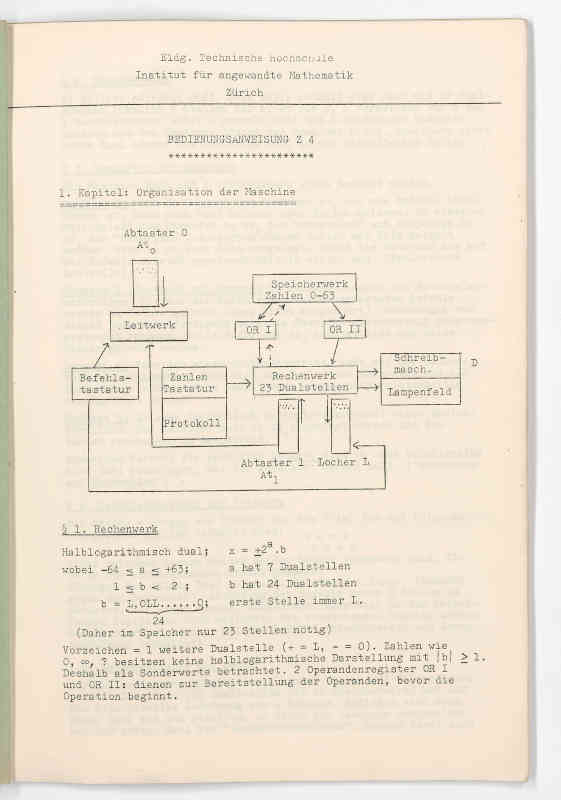

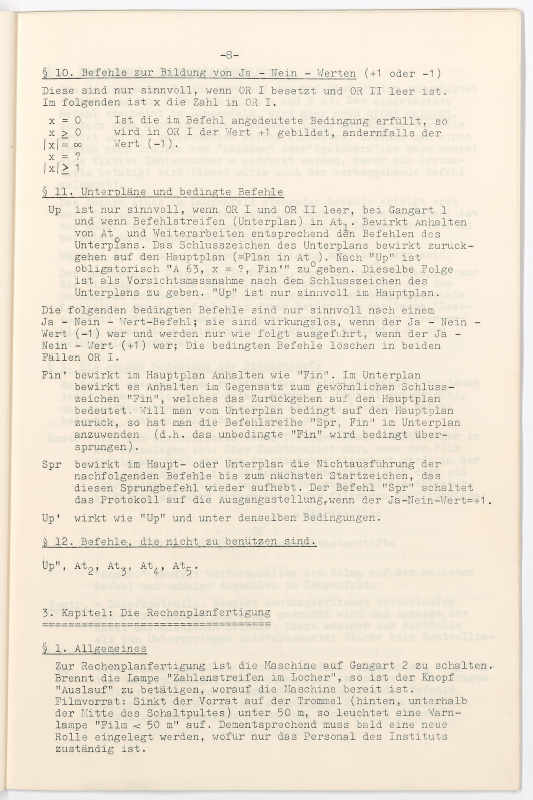

When we go further back into computer history, we find machines that became incomprehensible over time without their operating instructions. Such was the case with the Zuse Z4, “considered the oldest preserved digital computer in the world,” notes Vice. “The Z4 is one of those machines that takes up a whole room, runs on magnetic tapes, and needs multiple people to operate. Today it sits in the Deutsches Museum in Munich, unused. Until now, historians and curators only had a limited knowledge of its secrets because the manual was lost long ago.”

The computer’s inventor, Konrad Zuse, first began building it for the Nazis in 1942, then refused its use in the VI and V2 rocket program. Instead, he fled to a small town in Bavaria and stowed the computer in a barn until the end of the war. It wouldn’t see operation until 1950. The Z4 proved to be “a very reliable and impressive computer for its time,” Sarah Felice writes. “With its large instruction set it was able to calculate complicated scientific programs and was able to work during the night without supervision, which was unheard of for this time.”

These qualities made the Zuse Z4 particularly useful to the Institute of Applied Mathematics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), where the computer performed advanced calculations for Swiss engineers in the early 50s. “Around 100 jobs were carried out with the Z4 between 1950 and 1955,” writes Herbert Bruderer, retired ETH lecturer. “These included calculations on the trajectory of rockets… on aircraft wings…” and “on flutter vibrations,” an operation requiring “800 hours machine time.”

René Boesch, one of the airplane researchers working on the Z4 in the 50s kept a copy of the manual among his papers, and it was there that his daughter, Evelyn Boesch, also an ETH researcher, discovered it. (View it online here.) Bruderer tells the full story of the computer’s development, operation, and the rediscovery of its only known copy of operating instructions here.

Related Content:

The First Pizza Ordered by Computer, 1974

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply