You may have seen every single one of Studio Ghibli’s animated films, going well beyond the Hayao Miyazaki-directed My Neighbor Totoro, Spirited Away, and Kiki’s Delivery Service to the less widely known but also charmingly crafted likes of Ocean Waves, My Neighbors the Yamadas, and The Cat Returns. Even so, the question remains: have you really seen them all? Experiencing them in the theater or on home video is only the first stage of the process. Ideally, each element of a Ghibli movie should subsequently be appreciated in isolation and at length: by listening to the music, for example, hundreds of hours of which, available to stream, we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture.

Still, no matter how captivating Joe Hisaishi’s scores may sound on their own, Ghibli’s work is ultimately made to be seen. Given that 24 frames of their movies go by each second, it can be difficult to pick up all the details their animators include in each and every one of them.

Hence the value of the free archive of stills that the studio first made available online a few years ago, and that has steadily expanded ever since. Though only available in Japanese, it doesn’t present a great challenge even to fans with no knowledge of the language to click on the poster of their Ghibli film of choice, then to browse the variety of downloadable images associated with it.

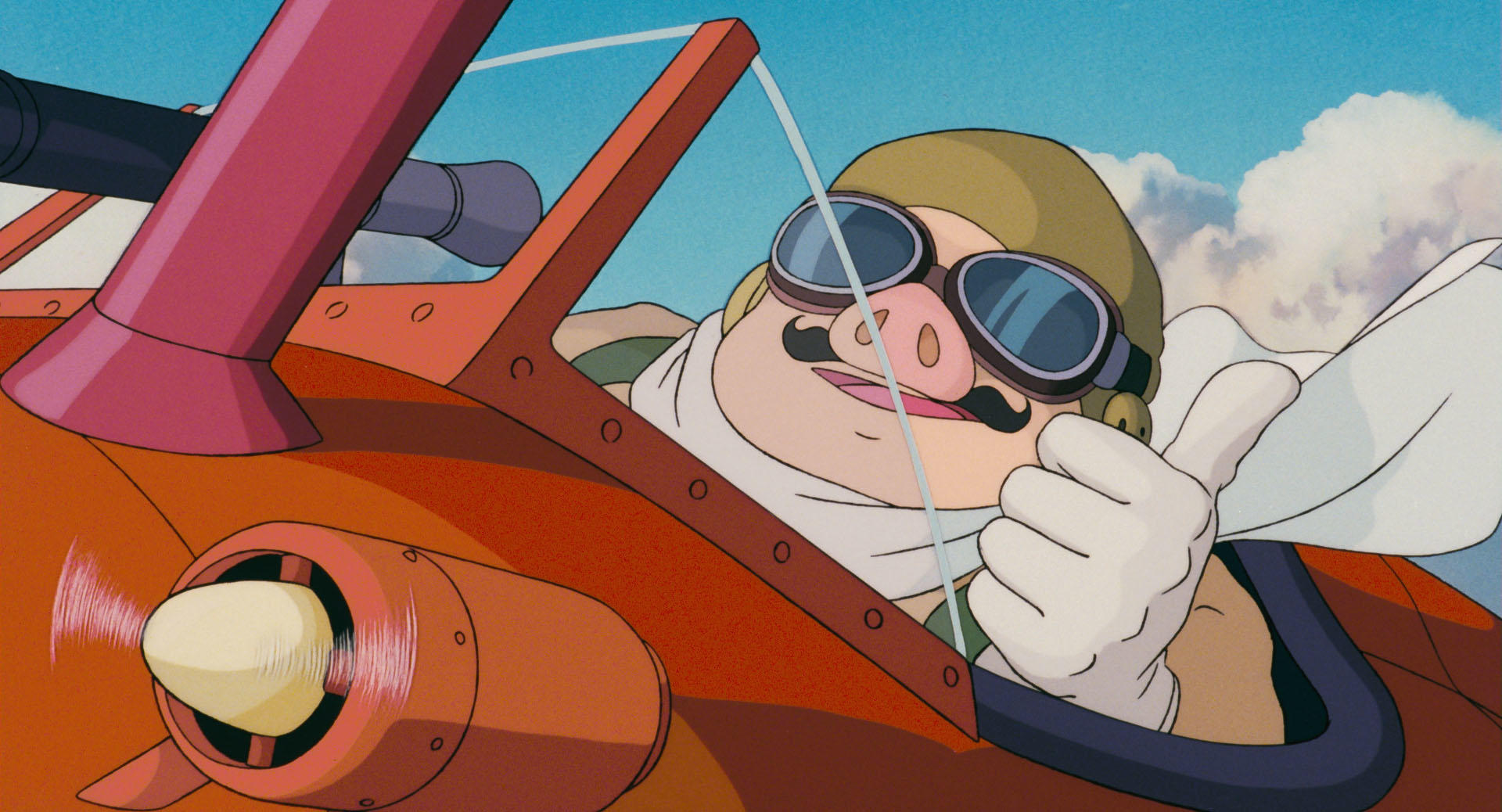

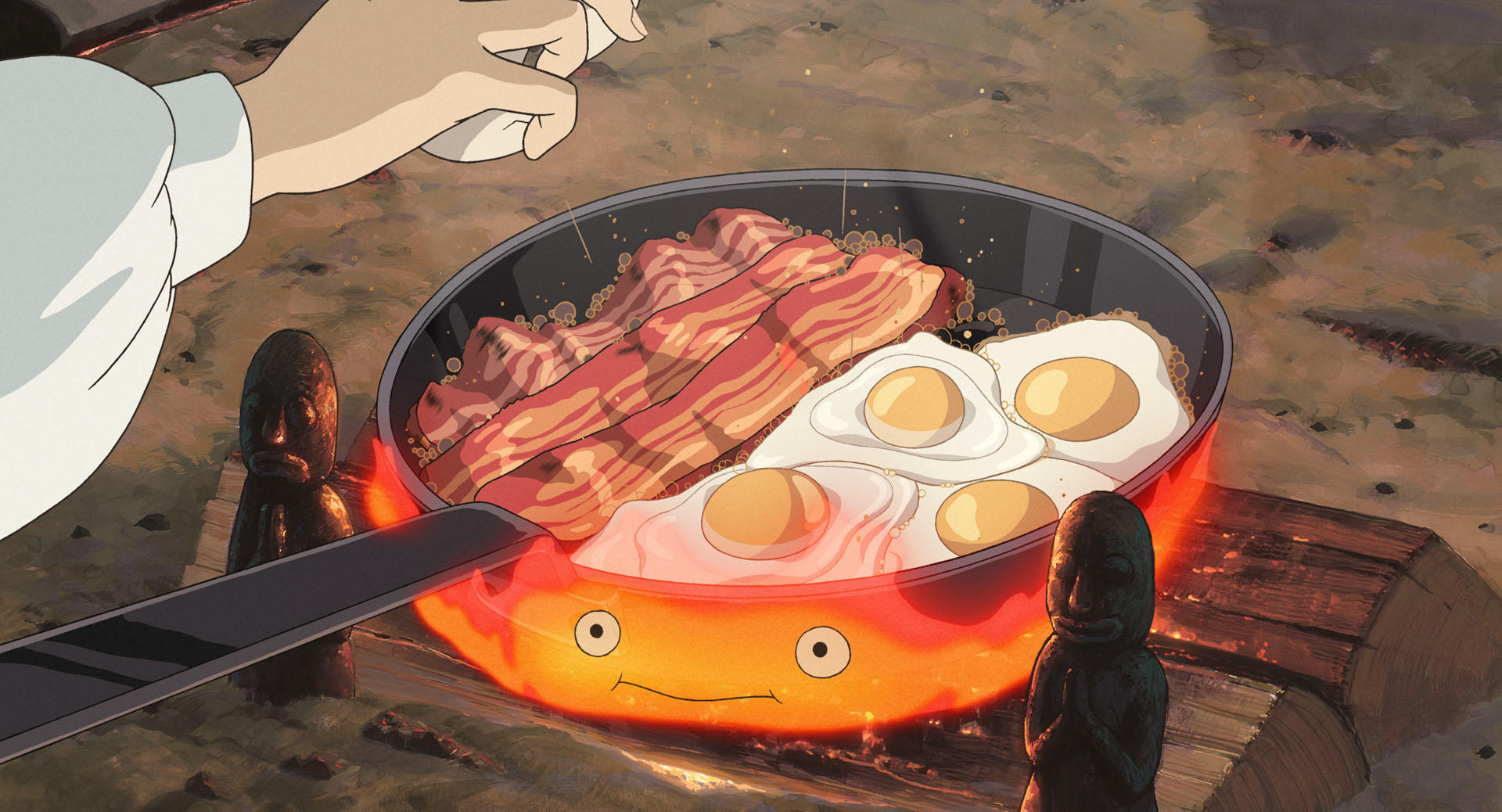

Many of these stills are drawn from highly memorable moments across the Ghibli filmography: the children’s party on the hero of Porco Rosso’s beloved airplane; the emergence of the kodama in Princess Mononoke; the defeat of the colossal Giant Warrior in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (which predates the studio’s foundation, but in any case now seems to count honorarily among its productions); the sentient flame cooking a skillet of bacon and eggs in Howl’s Moving Castle. Some of them have even been turned into wallpaper for video calls, downloadable from a page of their own. There we have another way to add a touch of Studio Ghibli’s distinctive vision to our everyday lives — and another source of inspiration to watch through the movies themselves one more time.

Enter the archive of still images here.

Related Content:

De-Stress with 30 Minutes of Relaxing Visuals from Director Hayao Miyazaki

A Virtual Tour Inside the Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli Museum

Software Used by Hayao Miyazaki’s Animation Studio Becomes Open Source & Free to Download

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.