In 79 AD, 17-year-old Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, known as Pliny the Younger, gazed across the Bay of Naples from his vacation home in Misenum and watched Mount Vesuvius erupt. “Darkness fell, not the dark of a moonless or cloudy night,” Pliny wrote in his eyewitness account — the only surviving such document — “but as if the lamp had been put out in a dark room.” Unbeknownst to Pliny and his famous uncle, Pliny the Elder, admiral of the Roman navy and revered naturalist, hundreds of lives were also snuffed out by lava, clouds of smoke and ash, and temperatures in the hundreds of degrees Fahrenheit. The Elder Pliny launched ships to attempt an evacuation. In the morning, he was found dead, likely from asphyxiation, along with over two thousand residents of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

When the buried town was first unearthed, a new cycle of witness, death, and resurrection began. “Since its rediscovery in the mid-18th century,” writes National Geographic, “the site has hosted a tireless succession of treasure hunters and archeologists,” not to mention tourists — starting with aristocratic gentlemen on their Grand Tour of Europe. In 1787, Goethe climbed Vesuvius and gazed into its crater. “He recorded with disappointment that the freshest lava was already five days old, and that the volcano neither belched flame nor pelted him with stones,” writes Amelia Soth in an article about “Pompeii Mania” among the Romantics, a passion that culminated in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1834 potboiler, The Last Days of Pompeii, “hands-down the most popular novel of the age.”

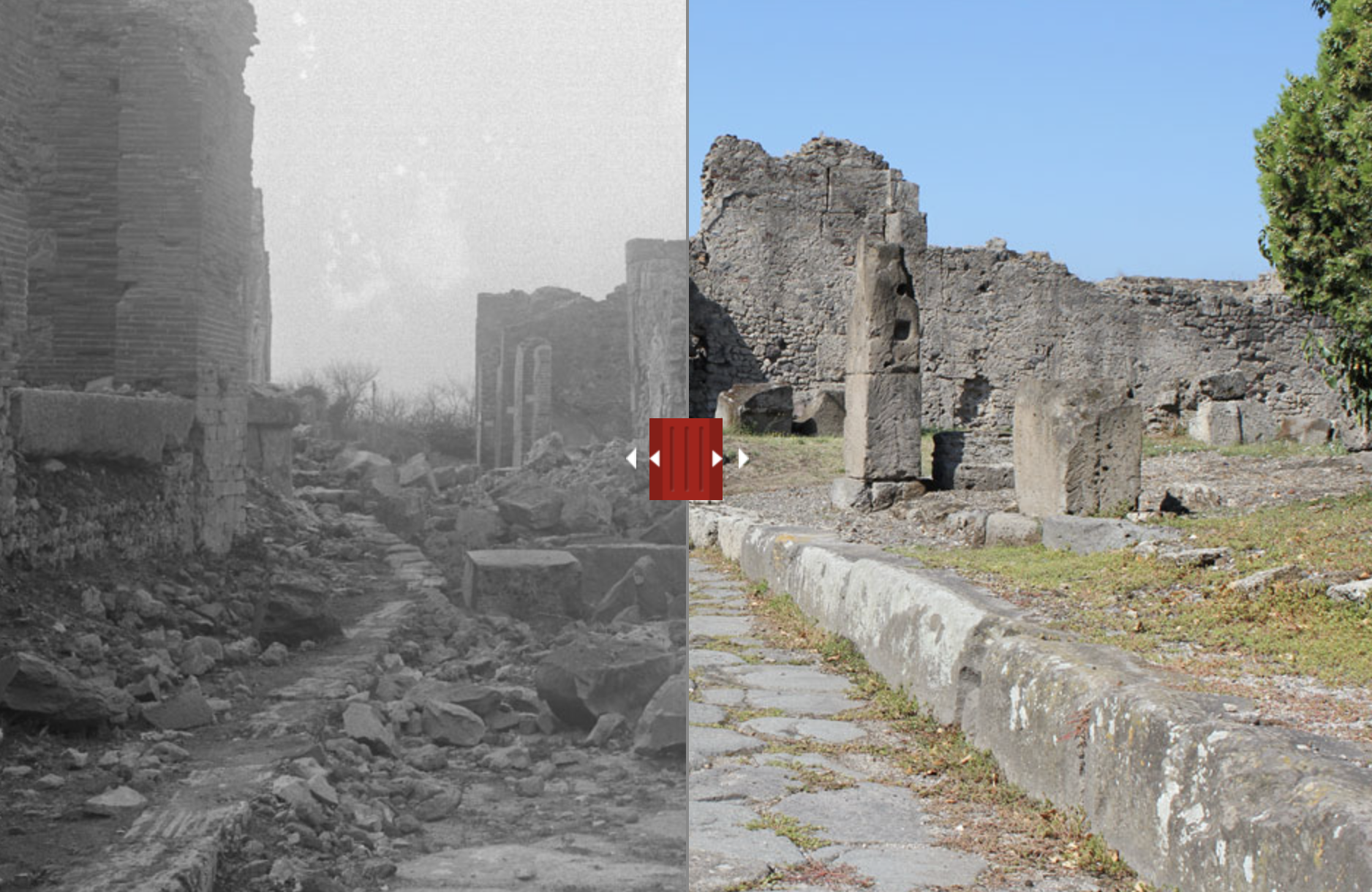

Bulwer-Lytton’s book “had such a dramatic impact on how we think about Pompeii,” the Getty writes, that the museum named an exhibition after it that features — unlike so many other histories — Pompeii’s 20th century “apocalypse”: an Allied bombing raid in the autumn of 1943 that damaged nearly every part of the site, including “some of Pompeii’s most famous monuments, as well as its museum.” As Nigel Pollard shows in his book Bombing Pompeii, over 160 Allied bombs hit Pompeii in August and September. Few tourists who now flock to the site know how much of the ruins have been rebuilt since then. “Only recently have the literature and the scientific community paid due attention to these dramatic events, which constitute a fundamental watershed in the modern history of the site,” writes archeologist Silvia Bertesago.

A Pliny of his time (an Elder, given his decades of scientific accomplishment), Pompeii’s superintendent, archeologist Amedeo Maiuri, “accelerated the protection of buildings and moveable items” in advance of the bombing raids. But “who will save monuments, houses and paintings from the fury of the bombardments?” he wrote. Maiuri had warned of the coming destruction, and when false information identified the slopes of Vesuvius as a German hideout, the longest-running archeological excavation in the world became “a real target of war.… The first bombing of Pompeii took place on the night of August 24 1943.… Between August 30 and the end of September, several other raids followed by both day and night.… No part of the excavations was completely spared.”

Maiuri chronicled the destruction, writing:

It was thus that from 13 to 26 September Pompeii suffered its second and more serious ordeal, battered by one or more daily attacks: during the day flying low without fear of anti-aircraft retaliation; at night with all the smoke and brightness of flares […]. During those days no fewer than 150 bombs fell within the excavation area, scattered across the site and concentrated where military targets were thought to be.

Himself wounded in his left foot by a bomb, Maiuri helped draw up a list of 1378 destroyed items and over 100 damaged buildings. Hasty, emergency rebuilding in the years to follow would lead to the use of “experimental materials” like reinforced concrete, which “would later prove incompatible with the original materials” and itself require restoration and repair. The ruins of Pompeii were rebuilt and resurrected after they were nearly destroyed a second time by fire from the sky — this time entirely an act of humankind. But the necropolis would have its revenge. The following year, Vesuvius erupted, destroying nearly all of the 80 B‑25 bombers and the Allied airfield at the foot of the mountain.

In the video above, you can learn more about the bombing of Pompeii. See photographs of the destruction at Pompeii Commitment and at the Getty Museum, which features photos of Pompeiian sites destroyed by bombing side-by-side with color images of the rebuilt sites today. These images are dramatic, enough to make us pay attention to the seams and joints if we have the chance to visit, or revisit, the famous archeological site in the future. And we might want to ask our guide if we can see not only the ruins of the natural disaster, but also the multiple undetonated bombs from the “apocalypse” of World War II.

Related Content

Pompeii Rebuilt: A Tour of the Ancient City Before It Was Entombed by Mount Vesuvius

A Drone’s Eye View of the Ruins of Pompeii

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness