When one considers which artists most powerfully evoke the horrors of trench warfare, Claude Monet is hardly the first name to come to mind. And yet, once viewed that way, his final Water Lilies paintings — belonging to a series that, in reproduction, speaks to many of no more harrowing a setting than a doctor’s waiting room — can hardly be viewed in any other. These eight large-scale canvasses constitute “a war memorial to the millions of lives tragically lost in the First World War,” argues Great Art Explained creator James Payne. Monet declined to include a horizon line in any of them, leaving viewers in “a vast field of unfathomable nothingness, of light, air, and water,” at once peaceful and reminiscent of “the battle-ravaged landscape along the western front.”

Those battlefields “had no beginning or end, and no horizons. Time and space was forgotten, as soldiers were enveloped in a sea of mud, surrounded by waterlogged and surreal landscapes, which covered their field of vision.” The Great War, as it was then known, still raged on when the septuagenarian Monet began these works. (“He could hear the sound of gunfire from 50 kilometers away from his house in Giverny as he painted,” notes Payne.)

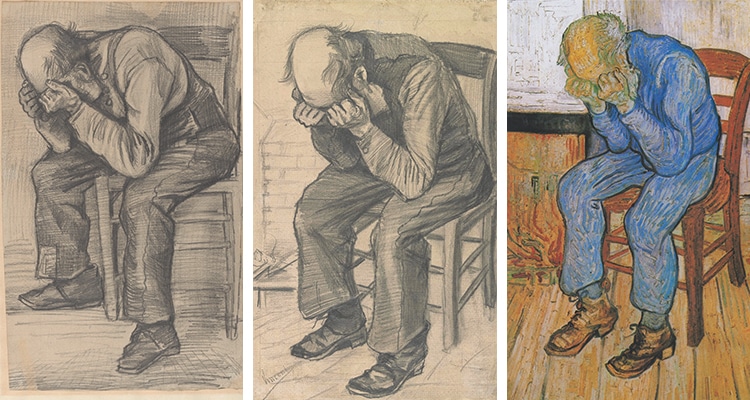

By the time he finished them, in the last year of his life, the fighting had been over for eight years. In a sense, these paintings may have kept him alive: “He was constantly ‘reworking’ them and seemed incapable of finishing,” even though, by his own admission, “he could no longer see the details or make out colors.”

When these Water Lilies were revealed to the public, mounted in their own specially designed gallery in Paris’ Musée de l’Orangerie (arranged by close personal friend Georges Clemenceau), Monet was dead — which may, in part, explain the critics’ willingness to deride them as the work of an artist who had lost his powers. “Monet, rejected by critics in the 19th century for being too radical, was now being criticized in the 20th century for not being radical enough.” It would take a later generation of artists — including American painters like Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock — to see his last works as “a logical jumping-off point for abstraction,” and the space that houses them as “the Sistine Chapel of impressionism.” World War I has passed out of living memory, but “the world’s first art installation” it inspired Monet to create has lost none of its power.

Related Content:

How to Paint Water Lilies Like Monet in 14 Minutes

Rare 1915 Film Shows Claude Monet at Work in His Famous Garden at Giverny

1923 Photo of Claude Monet Colorized: See the Painter in the Same Color as His Paintings

1,540 Monet Paintings in a Two Hour Video

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.