What is fascism? Fascism is an ideology developed and elaborated in early 20th-century Western Europe and enabled by technology, mass media, and weapons of war. Most of us learned the basics of that development from grade school history textbooks. We generally came to appreciate to some degree — though we may have forgotten the lesson — that the phrase “creeping fascism” is redundant. Fascism stomped around in jackboots, smashed windows and burned Reichstags before it fully seized power, but its most important action was the creeping: into language, media, education, and religious institutions. None of these movements arose, after all, without the support (or at least acquiescence) of those in power.

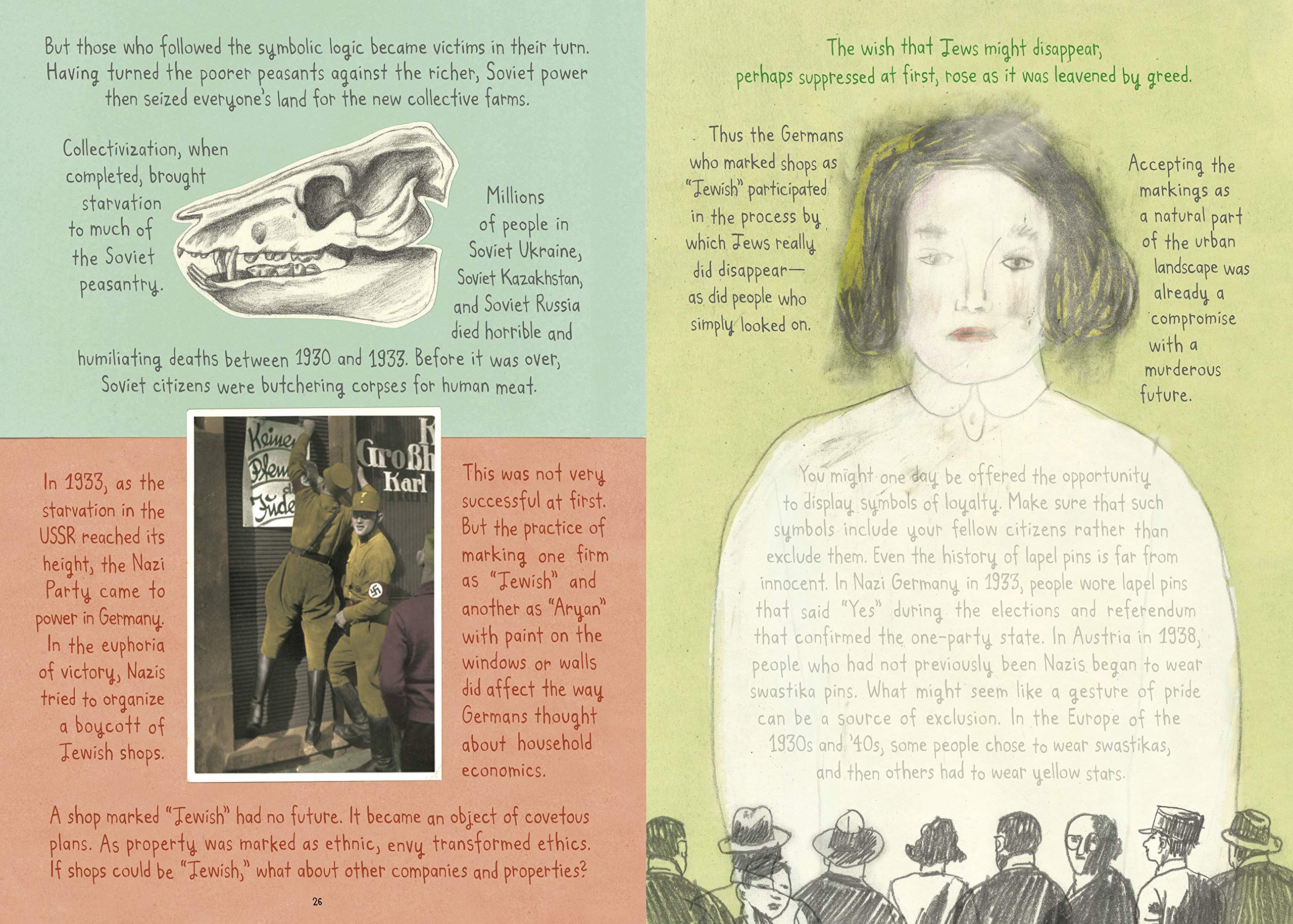

There are differences between Italian Fascism, German Nazism, and their various nationalist descendents. Mussolini secured power chiefly through intimidation. But once he was appointed prime minister by the King in 1922 he began consolidating his dictatorship, a process that took several years and required such dealings as the creation of Vatican City in 1929 to secure the Church’s goodwill. Some later fascist leaders, like Augusto Pinochet, came to power in coups (with the support of the CIA). Others, like Hitler, won elections, after a decade of “creeping” into the culture by normalizing nationalist pride based on racial hierarchies and nursing a sense of aggrieved persecution among the German people over perceived humiliations of the past.

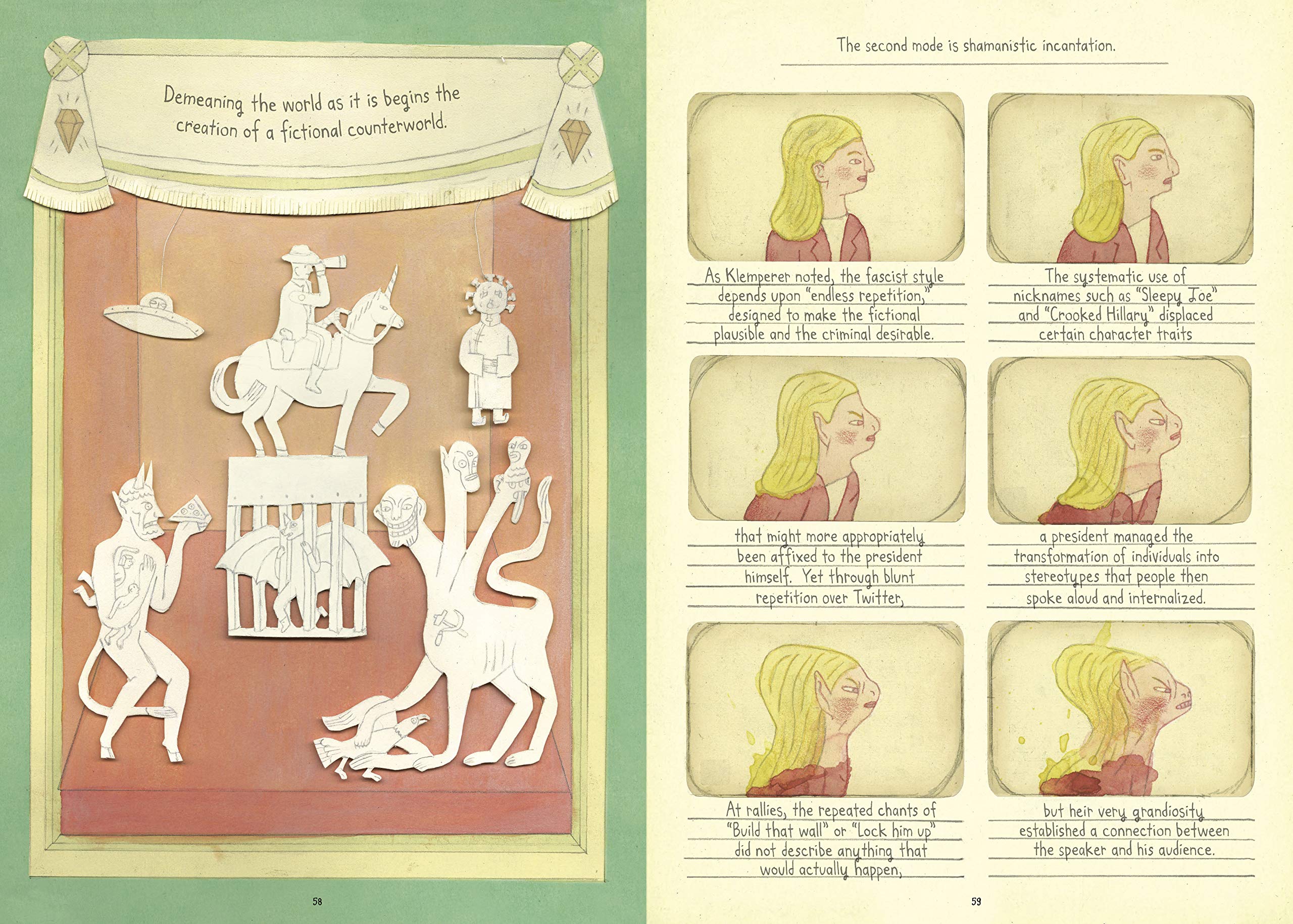

In every case, leaders exploited local hatreds and inflamed ordinary people against their neighbors with the constant repetition of an alarming “Big Lie” and the promises of a strongman for salvation. Every similar movement that has arisen since the end of WWII, says Yale University Professor of Philosophy Jason Stanley in the video above, has shared these characteristics: using propaganda to create an alternate reality and paying obeisance to a “cult of the leader,” no matter how repugnant his tactics, behavior, or personality. “Right wing by nature,” fascism’s patriarchal structure appeals to conservatives. While it mobilizes violence against minorities and leftists, it seduces those on the right by promising a share of the spoils and validating conservative desires for a single, unifying national narrative:

Fascism is a cult of the leader. It involves the leader setting the rules about what’s true and false. So any kind of expertise, reality, all of that is a challenge to the authority of the leader. If science would help him, then he can say, “Okay, I’ll use it.” Institutions that teach multiple perspectives on history in all its complexity are always a threat to the fascist leader.

Rather than simply destroying institutions, fascists twist them to their own ends. The arts, sciences, and humanities must be purged of corrupting elements. Those who resist face job loss, exile or worse. The important thing, says Stanley, is the sorting into classes of those who deserve life and property and those who don’t.

[O]nce you have hierarchies set up, you can make people very nervous and frightened about losing their position on that hierarchy. Hierarchy goes right into victimhood because once you convince people that they’re justifiable higher on the hierarchy, then you can tell them that they’re victims of equality. German Christians are victims of Jews. White Americans are victims of Black American equality. Men are victims of feminism.

The appeal to “law and order,” to police state levels of control, only applies to certain threatening classes who need to be put back in their place or eliminated. It does not apply to those at the top of the hierarchy, who recognize no constraints on their actions because they perceive themselves as threatened and in a state of emergency. It’s really the immigrants, leftists, and other minorities who have taken over, “and that’s why you need a really macho, powerful, violent response”:

Law and order structures who’s legitimate and who’s not. Everywhere around the world, no matter what the situation is, in very different socioeconomic conditions, the fascist leader comes and tells you, “Your women and children are under threat. You need a strong man to protect your families.” They make conservatives hysterically afraid of transgender rights or homosexuality, other ways of living. These are not people trying to live their own lives. They’re trying to destroy your life, and they’re coming after your children. What the fascist politician does is they take conservatives who aren’t fascist at all, and they say, “Look, I know you might not like my ways. You might think I’m a womanizer. You might think I’m violent in my rhetoric. But you need someone like me now. You need someone like me ’cause homosexuality, it isn’t just trying for equality. It’s coming after your family.”

Stanley offers several historical examples for his assessment of what he breaks down into a total of 10 tactics of fascism. (See an earlier video here in which he discusses 3 characteristics of the ideology.) Like Umberto Eco, who identified 14 characteristics of what he called “ur-fascism” in a 1995 essay, Stanley notes that “not all terrible things are fascist. Fascism is a very particular ideological structure” that arose in a particular time and place. But while its stated aims and doctrines are subject to change according to the psychology of the leader and the national culture, it always shares a certain grouping, or “bundle,” of features.

Each of these individual elements is not in and of itself fascist, but you have to worry when they’re all grouped together, when honest conservatives are lured into fascism by people who tell them, “Look, it’s an existential fight. I know you don’t accept everything we do. You don’t accept every doctrine. But your family is under threat. Your family is at risk. So without us, you’re in peril.” Those moments are the times when we need to worry about fascism.

Below we’re adding Stanley’s recent interview where he explains how America has now entered fascism’s legal phase. You can read his related article in The Guardian.

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness