Dilbert creator Scott Adams once wrote of his early experiences introducing the World Wide Web to others. “In 1993, there were only a handful of Web sites you could access, such as the Smithsonian’s exhibit of gems. Those pages were slow to load and crashed as often as they worked.” But those who witnessed this technology in action would invariably “get out of their chairs their eyes like saucers, and they would approach the keyboard. They had to touch it themselves. There was something about the internet that was like catnip.” In the intervening decades, the technology powering the internet has only improved, and we’ve all felt how greatly that catnip-like effect has intensified. And the Smithsonian, as we’ve featured here on Open Culture, is still there — now with much more online than gems.

Today, the Smithsonian’s impressive online collections are accessible through Artvee, a new search engine for downloadable high-resolution, public domain artworks. So are the collections of more than 40 other international institutions, from the New York Public Library and the Art Institute of Chicago to the Rijksmuseum and Paris Musées, many of which had little or no online presence back in the early 1990s.

In recent years, they’ve gotten quite serious indeed about digitizing their holdings and making those digitizations freely available to the world, uploading them by the thousand, even by the million. With so many artworks and artifacts already up, and surely much more to come, the question becomes how best to navigate not just one of these collections, but all of them.

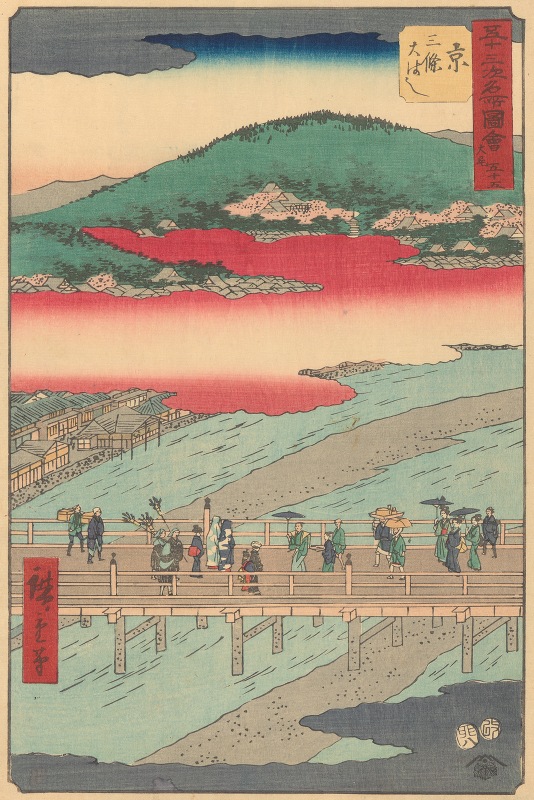

Artvee constitutes one answer to this question. Using its search engine, writes Denise Tempone at Domestika, “you can filter categories such as abstract art, landscape, mythology, drawings, illustrations, botany, fashion, figurative art, religion, animal, desserts, history, Japanese art, and still life. The site also gives you the option to search by artist. You will find works by Rembrandt van Rijn, Claude Monet, Raphael, and Sandro Botticelli in this amazing gallery.” Other collections, created by Artvee itself as well as by its users, include “illustrations from fairy tales; covers of popular American songs; and some even more peculiar ones, such as adverts selling bicycles that are over a hundred years old.”

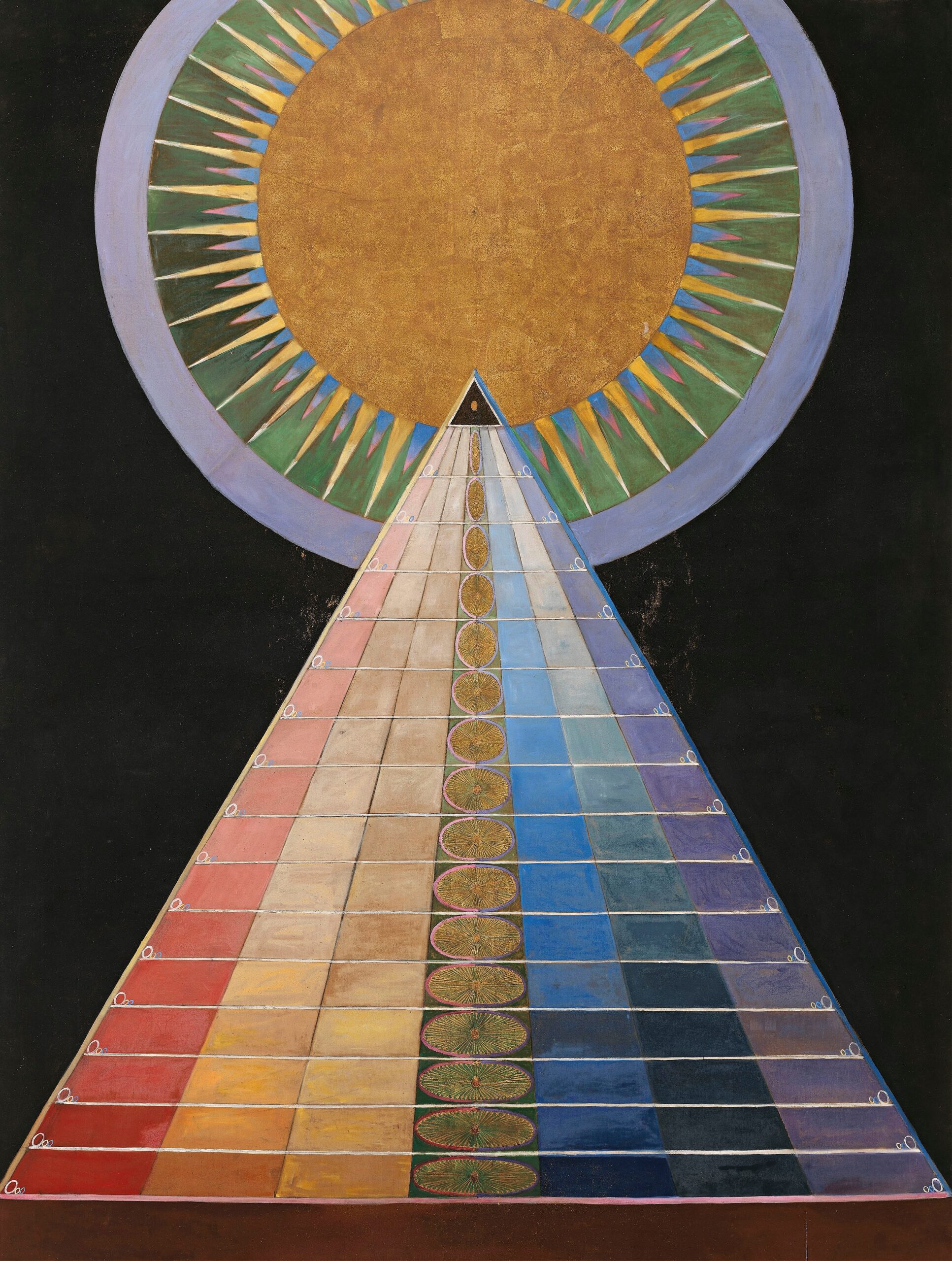

The variety of artists browsable on Artvee also includes Alphonse Mucha, Edvard Munch, and Hilma af Kint; other collections offer the wonders of political illustrations, book promo posters, and NASA’s visions of the future. All of the items within, it bears repeating, are in the public domain or distributed under a Creative Commons license, meaning you can use them not just as sources of inspiration but as ingredients in your own work as well, a possibility few us could have imagined at the dawn of the Web. Back then, you’ll recall, we all used a variety of different tools and portals to navigate the internet, according to personal preference. The emerging field of art search engines, which includes not just Artvee but other options like Museo, may remind us of those days — and how far the internet has come since.

Related Content:

A Search Engine for Finding Free, Public Domain Images from World-Class Museums

Visit 2+ Million Free Works of Art from 20 World-Class Museums Free Online

The Smithsonian Puts 2.8 Million High-Res Images Online and Into the Public Domain

14 Paris Museums Put 300,000 Works of Art Online: Download Classics by Monet, Cézanne & More

Flim: a New AI-Powered Movie-Screenshot Search Engine

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.