That quivering teacup Chihuahua…

The long-suffering Labrador whose child-friendly reputation has led to a lifetime of ear tugging and tail pulling…

The wheezing French bulldog, whose owner has outfitted with a full wardrobe of hoodies, tutus, rain slickers, and pajamas…

All descended from wolves.

As anthropologist and science educator David Ian Howe explains in the animated TED-Ed lesson, A Brief History of Dogs, above, at first glance, canis lupus seemed an unlikely choice for man’s best friend.

For one thing, the two were in direct competition for elk, reindeer, bison, and other tasty prey wandering Eurasia during the Pleistocene Epoch.

Though both hunted in groups, running their prey to the point of exhaustion, only one roasted their kills, creating tantalizing aromas that drew bolder wolves ever-closer to the human camps.

The ones who willingly dialed down their wolfishness, making themselves useful as companions, security guards and hunting buddies, were rewarded come suppertime. Eventually, this mutually beneficial tail wagging became full on domestication, the first such animal to come under the human yoke.

The intense focus on purebreds didn’t really become a thing until the Victorians began hosting dog shows. The push to identify and promote breed-specific characteristics often came at a cost to the animals’ wellbeing, as Neil Pemberton and Michael Worboys point out in BBC History Magazine:

…the improvement of breeds towards ‘perfection’ was controversial. While there was approval for the greater regularity of type, many fanciers complained that standards were being set on arbitrary, largely aesthetic grounds by enthusiasts in specialist clubs, without concern for utility or the health of the animal. This meant that breeds were changing, and not always for the better. For example, the modern St Bernard was said to be a beautiful animal, but would be useless in Alpine rescue work.

Cat-fanciers, rest assured that the opposition received fair and equal coverage in a feline-centric TED-Ed lesson, published earlier this year.

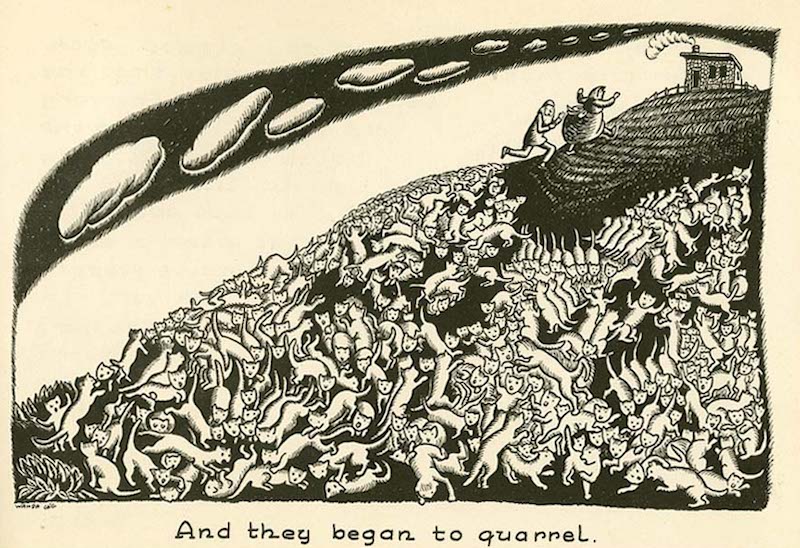

And while we applaud TED-Ed for sparking our curiosity with its “Brief History of” series, covering topics as far ranging as cheese, numerical systems, goths, video games, and tea, surely we are not the only ones wondering why the late artist Keith Haring isn’t thanked or name checked in the credits?

Every canine-shaped image in this animation is clearly descended from his iconic barking dog.

While we can’t explain the omission, we can direct readers toward Jon Nelson’s great analysis of Haring’s relationship with dogs in Get Leashed:

They’re symbolic of unanswered questions, prevalent in the 80s: “Can I do this?” “Is this right?” “What are you doing?” “What is happening?” Dogs stand by people, barking or dancing along, sometimes in precarious scenarios, even involved in some of Haring’s explicitly sexual work. Dogs are neither approving nor disapproving of what people do in the images; their mouth angle is neutral or even happy. In some cases, human bodies wear a dog’s head, possibly stating that we know only our own enjoyment, unaware, like a dog, of life’s next stage or the consequences of our actions.

Visit Ethnocynology, David Ian Howe’s Instagram page about the ancient relationship between humans and dogs.

Related Content:

Photos of Famous Writers (and Rockers) with their Dogs

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City April 15 for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.