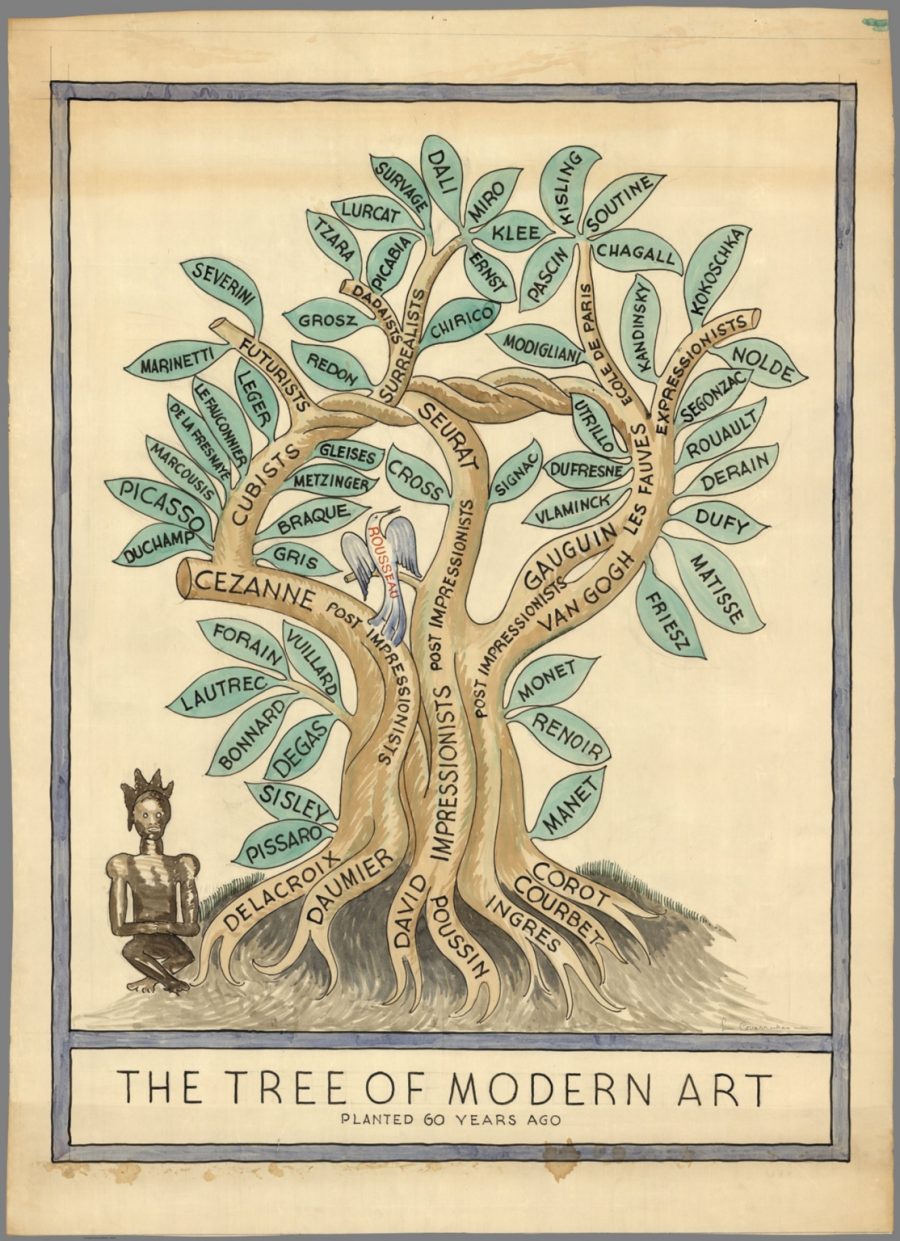

Selecting certain features, simplifying them, exaggerating them, and using them to provide a deep insight, at a glance, into the subject as a whole: such is the art of the caricaturist, one that Miguel Covarrubias elevated to another level in the early- to mid-20th century. Those skills, combined with his knowledge as an art historian, also served him well when he drew “The Tree of Modern Art.” This aesthetically pleasing diagram first appeared in Vanity Fair in May of 1933, a time when many readers of such magazines would have felt a great curiosity about how, exactly, all these new paintings and sculptures and such — many of which didn’t seem to look much like the paintings and sculptures they knew at all — related to one another.

“Because it stops in 1940, the tree fails to account for abstract expressionism and other post–World War II movements,” writes Vox’s Phil Edwards, in a piece that includes a version of the Covarrubias’ 1940 “Tree of Modern Art” revision with clickable examples of relevant artwork.

But “the organizational structure alone reveals a surprisingly large amount about the way art has evolved,” including how it “becomes broader and more inclusive over time,” eventually turning into a “global affair”; how “artistic schools have become more aesthetically diverse”; how “the canon evolved quickly”; and how “all art is intertwined,” created as it has so long been by artists who “work together, borrow from each other, and grow in tandem.”

You can also find the “Tree of Modern Art” at the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, a holding that illustrates, as it were, just how wide a swath of information design the term “map” can encompass. “The date is estimated based on the verso of the paper being a blue lined base map of the National Park Service dated 12/28/39,” says the collection’s site. “This drawing was found in the papers of B. Ashburton Tripp” — also a mapmaker in the collection — “and we assume that Covarrubias and Tripp were friends (verified by Tripp’s descendants) and that the blue line base map was something Tripp was working on in his landscape architecture business.”

The legend describes the tree as having been “planted 60 years ago,” a number that has now passed 130. Many more leaves have grown off those branches of impressionism, expressionism, post-impressionism, surrealism, cubism, and futurism in the years since Covarrubias drew the tree, but for someone to go back and augment such a fully-realized creation wouldn’t do at all — as with any work of art, modern or otherwise.

Related Content:

The History of Modern Art Visualized in a Massive 130-Foot Timeline

The Guggenheim Puts Online 1600 Great Works of Modern Art from 575 Artists

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.